“What just happened?” It pains me to admit this, but those were my first words upon climbing out of the Alpha Jet.

What happened was, in fact, an air combat engagement between two Discovery Air Defence Services (DADS) Alpha Jets and two CF-18 Hornets. Canadian Skies sent me to Cold Lake, Alta., to report on how DADS – formerly known as Top Aces – provides support to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). It was a great opportunity to see how fighter pilots work and train; but alas, it was also a bit like being a spectator at a brain surgery. As we will see, flying fighters is a very technical business – and training fighter pilots is likewise a challenging technical specialization; one at which DADS clearly excels.

Gentlemen, your mission

Our specific tasking was to support an air interdiction training mission for pilots from 410 Squadron, the RCAF’s CF-18 Hornet Operational Training Unit. Air interdiction is fighter pilot talk for blowing up tactically important ground targets. On this mission, the Hornet formation – the good guys wearing the proverbial white hats – would attack some imaginary dastardly villains who disregard fair play and justice. The Alpha Jets, wearing black hats, would attempt to defend against the Hornets.

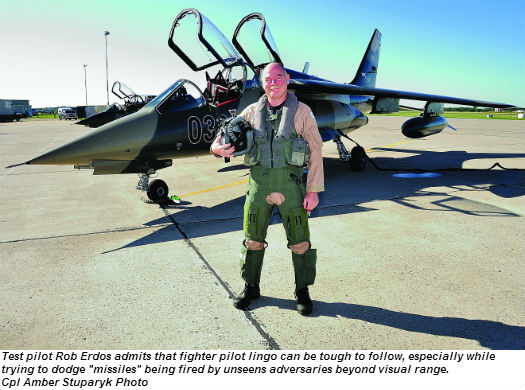

The pilot of “my” Alpha Jet, and my tour guide in the world of air combat, was Darren Cockell, call sign “Kaak.” No, I didn’t ask about the call sign. Fighter pilots receive their call signs in a mystical nocturnal naming ritual, the nature of which is a carefully guarded secret, although it is rumoured to involve a live goat and a tub of Cool Whip. I didn’t think my enquiries would get very far. In any case, Cockell’s fighter pilot credentials are impeccable. He’s been with DADS for almost five years; before that he flew several tours as a Canadian Air Force CF-18 fighter pilot. All of DADS’ pilots are experienced former RCAF fighter pilots, and most are graduates of the prestigious Fighter Weapons Instructor Course.

Meeting the enemy

This being a training mission, the good guys and the bad guys would meet for a pre-flight briefing. In the 410 Squadron briefing room, I met Captain Taylor “McLovin” Evans, a 410 Squadron Instructor Pilot. He would fly as “Stalker 51.” This mission was devoted to the training of two student fighter pilots, Captains P.C. Quiron and Sebastien Allard, who would fly a two-seat Hornet as “Stalker 52.” (Perhaps “baby” fighter pilots don’t get call signs.)

The opposing force would consist of two DADS Alpha Jets and one Hornet. Bob “Spider” Winram would lead our formation as “Cheetah 71.” Cockell and I would fly “Cheetah 72.” Our Hornet pilot, “Delta 81,” wasn’t at the briefing, but would make a programmed appearance at a selected point in the mission.

Quiron and Allard led a rapid-fire staccato briefing. There was no chit chat. They handed me a copy of the Mission Data Card. I regarded it studiously, and tried to nod thoughtfully at the right moments; but in truth, it was incomprehensible. It looked like a Klingon tax return!

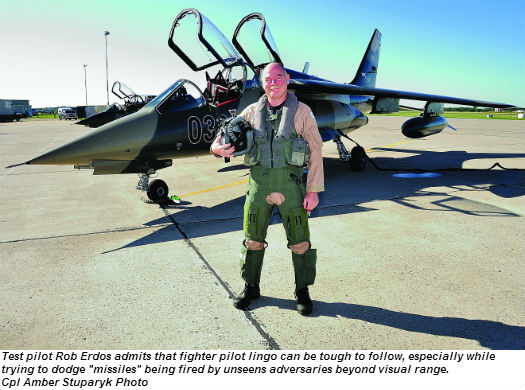

The briefing followed a closely scripted template which made my head spin. It was my first exposure to fighter pilot “lingo,” and I was soon lost. I recall a time hack and a mission overview with some entertaining fighter pilot hand gestures. They reviewed the weather, discussed airspace restrictions, and discussed the “training rules” with respect to their “hard deck” altitude, fuel minima, and other potential concerns. The exercise was scripted down to the second. I did glean that the Hornets would launch first and fly up to the north end of the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range, then turn around and attack toward the south. The Alpha Jets would launch last and defend from the south.

Following the briefing, Cockell privately described our objective as to “punish the Stalkers’ errors.” In so doing, we would enhance the students’ training by real-life trial and error. I was humbled to realize that, although I’m a professional test pilot and former military pilot, I had actually understood very little of what was discussed during the briefings. I was getting the idea that air combat was a highly technical business.

Strap in, blast off

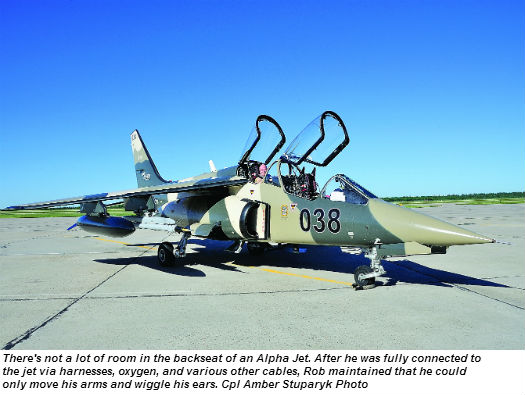

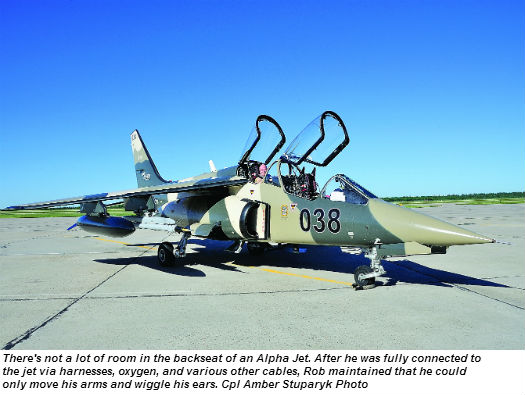

While Cockell did the pre-flight inspection, DADS technician John Maher helped install me in the Alpha Jet’s compact back seat. I was glad for Maher’s assistance because I wouldn’t have figured it out alone. By the time I was fully connected to the jet – harnesses, oxygen, life preserver, survival kit, leg garter bridles to the ejection seat, and communications cable – I could only move my arms and wiggle my ears. I was comfortable, but essentially immobilized for my own protection.

Cockell, meanwhile, awoke the jet. Engine start was audible as a quiet rumble beneath the Base radio chatter. The Alpha Jet is a simple machine. Within a few minutes our checks were complete, and we were ready to taxi.

En route to the runway, Cockell briefed our takeoff procedure: Nosewheel lift-off would occur at 122 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS). We could abort for any problem up to 145 KIAS and could safely fly away above 148 KIAS. For a small plane, the Alpha Jet seemed to operate at high speeds!

Our formation of Alpha Jets, Cheetah 71 and 72, rolled for takeoff in a 10-second sequence from Cold Lake’s Runway 31-Right. Takeoff acceleration was indeed exhilarating, and we overflew the departure end of the runway with an airspeed already well in excess of 200 KIAS. We climbed out into the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range at a lively 280 KIAS.

Shot down three times before lunch

Cockell established contact with the ground-controlled interception (GCI) operator, named “Sidecar,” a voice emanating from the NORAD command centre somewhere beneath North Bay, Ont. We carefully kept to the prescribed timeline for the sortie. The attack was supposed to start at precisely 10:05, and our formation was on station with about a minute to spare. “We take timing seriously,” Cockell advised, in an evident understatement.

We maintained “fighting wing,” a loose tactical formation where we stayed within a half mile laterally and 3,000 feet vertically of Cheetah 71. Within a minute “Sidecar” radioed: “Contact hostiles 12 o’clock, 60 miles.” Our formation split into a Soviet-style “swept formation, echelon southeast.” We were pretending to be MiG-23’s flying a “beam CAP.” That’s a combat air patrol. I was pleased, thinking that I was catching onto the jargon. I scanned the sky in anticipation of a dogfight, thinking that our war was about to begin.

“Two cons. Twelve o’clock.” Cockell was pointing out the contrails from the Hornets high above us in the distance. There was an unintelligible call on the radio. “We’re dead,” Cockell observed dryly. “I’m too young to die,” I muttered, disappointed. We hadn’t even maneuvered.

I wish I could report that the subsequent engagements were more dynamic. I had expected a dogfight; but in two further scenarios, our Alpha Jets assumed different defensive formations against the incoming Hornets, and in each case we were promptly despatched from beyond visual range by missiles. Each scenario was like a series of high speed chess moves. We deployed our forces to our advantage by different means, wherein the student fighter pilots “painted” us with their radar from a safe distance, interpreted our cunning intentions, and responded with what I can safely assume was the correct tactical maneuver. After all, we kept getting killed. The Hornets could have easily held their own had our formations merged into a classic dogfight, but the rules of engagement for our exercise allowed the Hornets to safely fire from beyond visual range, and that’s just what they did – with lethal effect.

During the second engagement, Delta 81 made an appearance off our left wing. As a defensive feint we “dragged” Delta 81, meaning that as the Stalker formation closed to within 35 miles of us, Delta 81 did a wide 360 degree turn to position itself about 15 miles in trail of our jet. The idea was to stagger our entry into the Hornet’s weapons range, so that Delta 81 might pose a threat with its radar while we got in close enough to engage. Apparently, that didn’t work. I’d love to report exactly what the CF-18s did, but the engagement once again occurred beyond visual range, so our first sign of trouble was being suddenly dead – again.

Our third engagement involved all three “bad guy” jets. This time, Cheetah 71 ran north toward the attacking Hornets with Cheetah 72 and Delta 81 following 15 miles in trail. Cockell had to point out Delta 81 off our wingtip in the distance. I was told that the Hornets would likely jink west to slow our rate of closure and to give their radar a better aspect upon our formation. “Shot,” I heard on the radio. “Kill” followed shortly thereafter. They meant me. I was getting used to it.

I spent most of my time in the Alpha Jet in a mild state of situational confusion. Clearly, one of the skills a fighter pilot develops is to synthesize situational awareness from the briefing, radio communications and radar displays. They call it “air picture,” and they learn to visualize not only where all of the other aircraft are; but also where they will be, whether they are a threat, and what to do about it. I just found it boggling.

Was this realistic training? Had we really been flying MiG-23s instead of Alpha Jets, we would have also had radar and missiles; however, the outcome would likely have been the same. The military doesn’t talk about the performance of radar or weapons, but the combatants in our exercise were quite aware of the performance of the simulated adversaries. When Cockell “called the kill,” it was no doubt based upon his understanding of the capabilities of both the Hornet and our simulated MiG. The 410 Squadron students prevailed against experienced adversaries using realistic tactics. Training doesn’t get much more real than that.

Aces in Alpha Jets

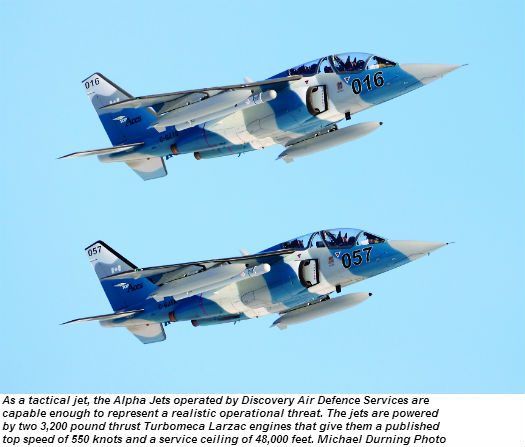

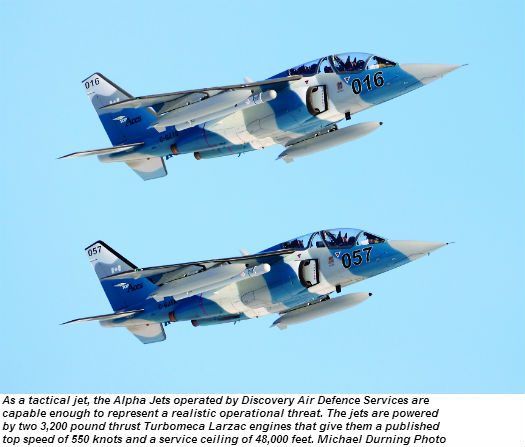

Cockell, and indeed everyone with whom I spoke at DADS, had nothing but praise for the Alpha Jet. As a tactical jet, it is simple enough to be robust and serviceable, but capable enough to represent a realistic operational threat. It is a two-place, twin-engine light attack jet and advanced trainer, jointly manufactured in the mid-80s by Dassault of France and Dornier of Germany. Its two 3,200 pound thrust Turbomeca Larzac engines give it a published top speed of 550 knots and a service ceiling of 48,000 feet.

Of course, the Alpha Jet isn’t perfect. When asked about his “wish list,” Cockell confessed that he missed having radar, and wished that DADS were approved for captive-carriage of missiles. There is also a desire to equip the Alpha Jet to drop live ordnance for training; a capability that would greatly enhance the instruction of Army forward air controllers. The jet is currently equipped with bomb racks, but I was teasingly told that their use is not authorized “yet.”

Discovery Air Defence Services (DADS) operates 16 Alpha Jets and a Bombardier Challenger from bases in Cold Lake, Bagotville, Victoria and Halifax, from which they offer combat training to all three branches of the military. For the Navy, DADS flies profiles simulating anti-shipping missiles and acts as sea skimming targets for naval gunners. The Army receives close air support training for their forward air controllers, and uses the DADS jets as surface-to-air gunnery targets. For the Air Force, the company provides electronic warfare training, aerial target towing….and, as in our case, airborne adversary training. A variety of pylon-mounted pods equip the Alpha Jet for specific roles.

After the mission, I asked Cockell if he could have won the fight had he been free to maneuver. He just smiled. Fighter pilots don’t suffer from a lack of confidence; however, his job was not to “spank” the baby fighter pilots, but rather to help train them. It might seem inglorious work to be repeatedly shot down like a target in a carnival arcade game, but the exercise is invaluable for the Air Force. It takes years to become fully qualified in the Hornet. Through DADS’ services, the Air Force avails itself of highly experienced fighter pilots who, among other tasks, serve as qualified adversaries. After being shot down three times in one morning, it was clear that DADS has a valuable role to play in support of the Air Force.