Estimated reading time 16 minutes, 16 seconds.

It’s not on any course syllabus, but before you attend the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California, pick up a copy of Tom Wolf’s 1979 book, The Right Stuff. Or better, watch the 1983 movie. More recent films have used the base as a backdrop, but The Right Stuff remains the definitive film about the test pilots who broke the sound barrier and launched the American astronaut program. It’s not only a primer on some of the key moments in aerospace history, but also a guide map to the many landmarks at Edwards. And lines from it may be quoted to you.

Major Maciej ‘Match’ Hatta appreciated that technological history the moment he arrived. “Within a span of minutes, I saw four different airplanes take off, including an unmanned Predator, an F-35 and a B-52.”

None would be among the more than 20 aircraft he flew during the year-long program, but the thundering roar of the active runway was an early indication of what was to come.

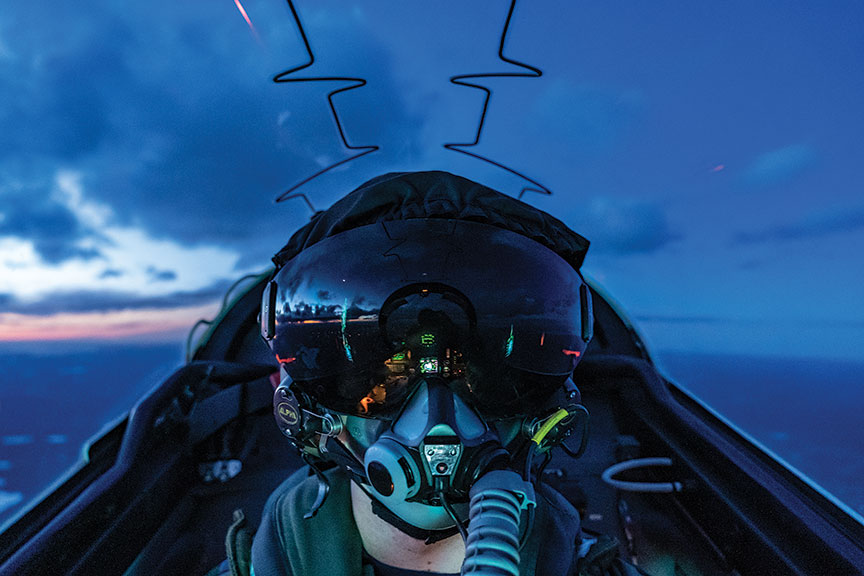

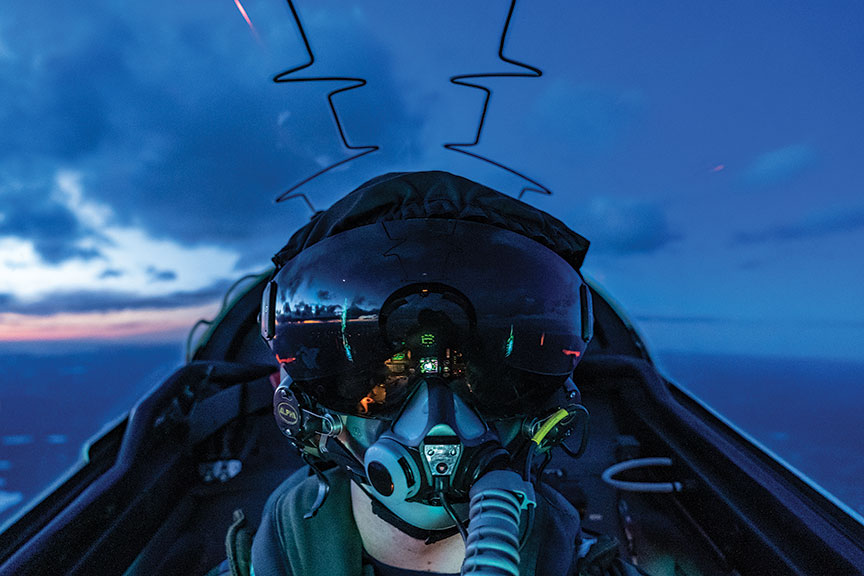

Hatta graduated with Class 20A from the USAF Test Pilot School in December 2020. A CF-188 Hornet fighter pilot and instructor, and a former member of the Canadian Forces Snowbirds with 431 Air Demonstration Squadron, he now serves as a Qualified Test Pilot with the Aerospace Engineering Test Establishment (AETE) in Ottawa, Ont., working on the Hornet Extension Program.

Becoming a test pilot is not for everyone – the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and AETE attempt to weed out early in the process those who might not succeed and thrive. But for Hatta, it was both the toughest year of his career “from a life management point of view” and an incredibly rewarding experience.

“For a future in the RCAF and in aviation, it’s an amazing opportunity to see things in a different light,” he said in a recent interview with Skies.

Each year AETE and the RCAF issue a call for candidates. During a gruelling two-week ‘tryout’ to determine suitability, prospects are given a crash course in the main pillars of flight test – performance, stability and control, and systems evaluations – and tasked to complete a data collection project flying an unfamiliar aircraft.

“Being a test pilot is all about learning to be comfortable being uncomfortable,” Hatta explained. “That is what AETE does during the tryout. It is wholly different from operational flying in the Air Force, so it is good for applicants to see that before committing. It’s a different mindset – less about tactics and being the pointy end of the spear and more about what the aircraft is doing or intended to be doing. You have to think more about the weapon system itself and its performance limits, and somewhat less about tactical applications.”

Though Hatta successfully completed the AETE trial in 2012, he was then offered the dream job on his RCAF career bucket list – a seat in a CT-114 with the Snowbirds. After weighing his options, he chose the aerobatic demonstration team. “I thought, if I do the test pilot course, I may not get this opportunity at a later date,” he said, “so I put test pilot on pause.” Between 2014 and 2017, he would fly Snowbird 6, the outer right wing, Snowbird 3, the inner left wing, and Snowbird 7, the outer left wing.

A second shot at test pilot school came soon after and this time he didn’t hesitate. By the summer of 2019, Hatta was completing medical exams and travel-related paperwork, verifying his math proficiency, and conducting centrifuge training at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, OH. A fighter pilot for much of his career, he was accustomed to high G-force environments. But the USAF Test Pilot School required a 9 G profile for F-16 Viper flights.

In December 2019, with his wife and daughter, Hatta made the six-day drive to Edwards AFB, the self described “center of the aerospace testing universe.”

TIME MANAGEMENT

Under agreements with the USAF Test Pilot School, U.S. Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River, MD, National Test Pilot School in California’s Mojave Desert, Empire Test Pilots’ School in the United Kingdom, and the École du personnel navigant d’essais et de reception (EPNER) in France, Canadian candidate test pilots and flight test engineers regularly attend 12-month programs to learn their craft. For fighter pilots, that usually means a year at Edwards or Pax River.

The 48-week USAF TPS program is “an exercise in time management,” said Hatta. It began in early January – his Alpha cohort were the junior members to a Bravo serial that began the previous July. He had been advised the course load would be intense, but was surprised how quickly “stressors” meant to replicate the normal pressures of a test pilot quickly began cascading down on him.

The program is centred around the three pillars of flight test. The first 24 weeks are an academic grind through the principles of aircraft performance and how to evaluate performance specifications; the mathematical equations of flying qualities such as lift, thrust weight, drag, stability and control, with an emphasis on understanding their implications for aircraft design; and the intricacies of aircraft systems, especially software, and the effect of program upgrades and changes on performance and safety. Each lesson within those three phases is like a university-level aeronautics course, with an exam every five to 10 days, he said.

While coursework and ground school occupy the mornings, the afternoons and evenings are for flying, often with an instructor, sometimes with a classmate. Students are assigned to a performance group tasked to collect and develop data on a particular aircraft. Hatta began with a team evaluating the Northrop, now Boeing, T-38C Talon jet trainer, flying with a test engineer in the back seat to gather the data.

“The overall objective of the project was to confirm the performance values to be able to sell the aircraft as a foreign military sale to a fictitious country. Ultimately, you are recreating parts of the flying manual to do that,” he explained. Other groups conducted the same exercise on an F-16, a Beechcraft C-12 Huron turboprop, and a Bombardier Learjet – the latter was configured for remotely piloted operators.

The T-38 was one of three “mainstay” aircraft on which Hatta collected performance data during the first 24 weeks; he even received his seat check and VFR captaincy in the aircraft. He also flew the F-16, gathering data on systems such as the radar and forward-looking infrared targeting pod, and the C-12 Huron.

“This is where time management really comes in,” he said of the morning academic program, afternoon flights and evenings working with his project team. “There isn’t time to do everything one hundred per cent, so you have to know when to cut off your time and devote more to where you most need to improve or can benefit.

“There would be a point where you’d have three or four projects coming up in different disciplines, and different aircraft even, one due on a Friday, one on a Monday, and you’d have to parse out [with the team] who was doing what. It really was a group effort in terms of managing resources and people, much like any test program to meet a deadline.”

The respite between the first and second halves of the program is a brief two weeks, with comprehensive exams scheduled shortly after courses resume. But Hatta rented a Volkswagen Westfalia camper and with the family toured the Pacific Coast Highway north to San Francisco for a week in July. “Well worth it,” he said.

TWENTY AIRCRAFT TYPES

The second 24 weeks are no less demanding than the first. Data collection and test projects continue to pile up, but the Alpha class students are now the senior members of the course and able to select their own projects from proposals sourced from across the USAF. An avid photographer and videographer who has created numerous videos of the Snowbirds, Hatta’s first project was right in his wheelhouse: A camera pod capturing pixel changes in intensity to support alternative navigation. Using altitude algorithms with the camera data, the Air Force hopes to compute alternative means of navigation in GPS-denied environments.

The latter half of the program “is also when you really start flying other aircraft,” he said. The exact number will vary year to year based on the availability of contractors who provide aircraft and instruction to students either at Edwards AFB or in other locations. In a normal year, that might range from 25 to 30 aircraft types.

“You’ll do some handling exercises and some performance work as well as qualitative evaluations on these aircraft,” said Hatta. “You are just broadening your experience base on different aircraft,” which might come into play if a project is on a similar type.

There is also an exchange week with the U.S. Navy Test Pilot School where students fly the Sikorsky HH-60 Jayhawk, the T-6 Texan trainer, and the F-18 Super Hornet. The pandemic nullified the exchange and affected some contractor availability. Still, Hatta surpassed 3,000 military flying hours while at Edwards, adding 100 unique hours to his logbook on 20 aircraft types.

In addition to his three mainstay test platforms, the flight hours included time in a Robinson R44; gliders, including the SGS 2-33 he flew in Air Cadets; the Aero L-39 Albatros and L-29 Delphin; a P-51 Mustang; a Bell UH-1 Iroquois ‘Huey’; a Canadair CT-133 Silver Star; a T6 Texan; and an Extra Flugzeugbau EA300 aerobatic monoplane – “the roll rates were insane; your eyes were still spinning for a few minutes afterward.”

He also flew the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III, dropping air loads onto a range. “That’s the first time I’ve ever flown something that large that reacted almost like a CF-188. The roll rate is fighter-esque.”

Among the more notable airframes was a Grumman HU-16 Albatross. His first encounter with the amphibian seaplane was a performance check ride as a junior student. “It was literally the first time flying the aircraft. We were notified the night before and expected to know enough to start, fly and land it and collect performance data on it. Your co-pilot is one of the contractors and you have a flight test engineer classmate on the flight deck collecting all the data. They put a time limit on you like an actual test program. You could have done the best data collecting, but if you couldn’t manage your time, you failed. That was a stressful flight.”

His second encounter with the bird was as a senior “when the juniors were stressing out and we got to fly it more for fun, out over the Hoover Dam, and do touch and goes and land it on Lake Mead.”

Hatta’s most memorable, though, was the F-16. “It was incredible to fly,” he said, “It is amazing what they can bolt onto such a small structure and yet get so much thrust out of it.”

AIRPLANE CRITIC

Exhilarating as the flying was, students are constantly reminded to assess each aircraft with a critical eye. Hatta initially assumed the inclination of the F-16 seat was related to G-force tolerance; he soon learned it was intended to ensure a sleeker design and reduce drag.

“That is what the latter part of the course really taught us. One professor strove to make us all airplane critics. You’d look at the backend and underneath the fuselage of an F-16 and wonder why those vertical dorsal fins are there. If you look at the top, it’s a supersonic fighter and there’s only one vertical stabilizer. It would probably suffer from directional stability issues, so they had to add some extra vertical surfaces to help stabilize it.

“You are taught to look at little design features and why they are there or predict how that aircraft would handle as a result of that design addition,” he added. “They don’t teach you to have all the answers, they teach you where to look and how to critically evaluate things and tap into other resources to find answers.”

One of the strengths of the USAF TPS program is the breadth of experience among its instructors, and the lessons they are willing to impart above and beyond the course curriculum. “We heard firsthand accounts of what they experienced in test flights” from programs such as the auto-ground collision avoidance system introduced on the F-16 and now on the F-35.

“Auto GCAS has saved lives and aircraft. A lot of people on staff were fundamental to that program early in the testing. They were able to show the impacts of real-world tests. They stressed a focus on the end user, that you want to be the first person to pick up on something, to figure out a flaw in system software logic, and not a junior wingman scrambling out of Cold Lake in the middle of the night by themselves who struggles how to handle it. You want that to be the experience of a professional test pilot.”

As with AETE, the resounding theme throughout the program was learning how to be comfortable being uncomfortable. Pilots normally try to avoid doing anything dangerous, dumb or different; test pilots are always doing something different, so flight discipline is essential to mitigate against the other two, Hatta said. “There is always something inherently dangerous in aviation testing of new systems or weapons, but there are risk mitigation steps, be it sanitized airspace or range space, a chase aircraft watching, or a build up approach. That was something each instructor emphasized in their own way.”

What advice would he pass on to others contemplating the test pilot career path? The demands on your time will challenge family life, but a year away from a Canadian winter and in relative proximity to Disneyland, the San Diego Zoo and Legoland might placate family members somewhat.

“Don’t be scared off by the math exams and the amount of hard work. It is hard but I made some incredibly close friends because we all had to work through the program together. It is a marathon.”

Excellent article that should be shared with all students of a Flight Test School. I am a staff FTE Instructor at ITPS, yeah, our own Canadian Test Pilot School. We have 3 RCAF FTE on the course currently (a first for the RCAF, but no Test Pilot yet). I would like to share this first hand account with them.