Estimated reading time 17 minutes, 44 seconds.

This summer, the CH-148 Cyclone was tested and found capable of operating in the northernmost reaches of the world. Although the Cyclone is considered a maritime helicopter, Canada’s original statement of operating intent envisioned global operations over land and sea. To realize that vision, some critical systems required further testing in Canada’s northern domestic airspace.

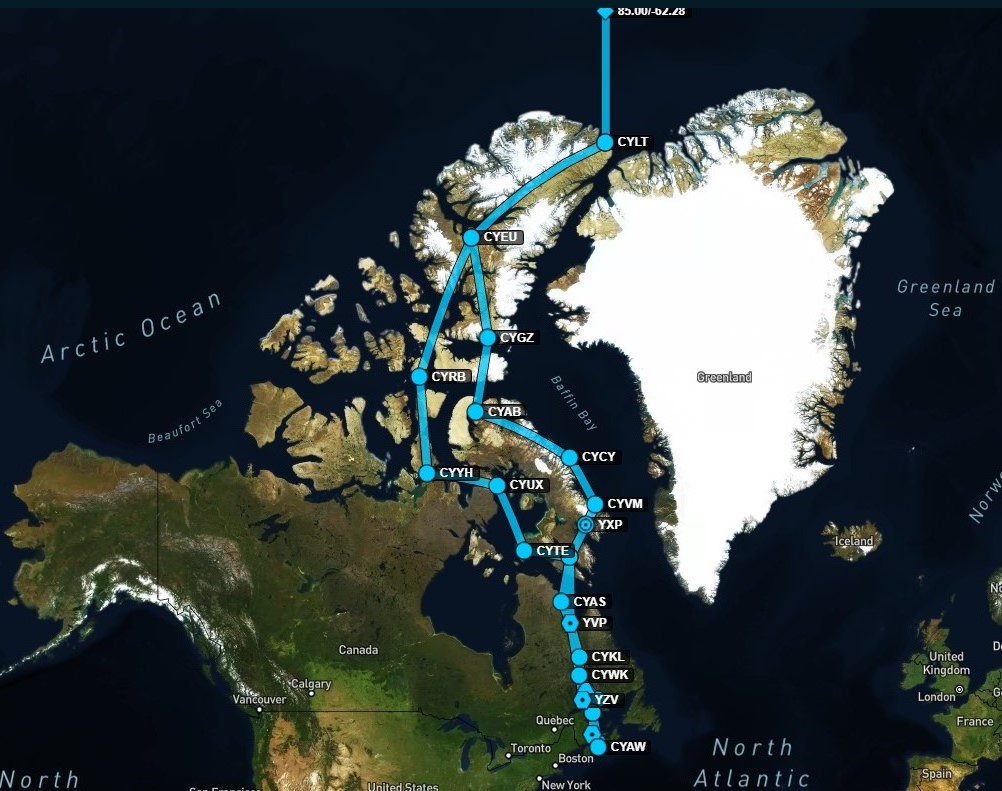

In 2019, planning began to send a Cyclone from its home base at 12 Wing Shearwater, Nova Scotia, to Alert, Nunavut – the world’s most northerly settlement.

“There were some sensors in the aircraft which are critical for the navigation and flight control system that were lacking a bit of technical data to show they would work everywhere,” explained Dany Duval, a civilian test pilot with the Aerospace Engineering Test Establishment (AETE).

The sensors in question were related to the EGI – or Embedded GPS INS – which is a combination between a GPS receiver coupled to an inertial navigation sensor within a single box. It assists with navigation, stabilization, and flight control applications.

To work properly, the INS needs to know where it is around the world. Once it knows where the Earth’s gravity is, it can provide pitch and roll information. The next step to align the EGI is to detect the Earth’s easterly force resulting from its rotation – but the higher north you go, the weaker this force becomes.

“That was the concern with this testing,” Duval explained. “The vendor of that component could only say it would work properly to 67 degrees north. So, the goal of the test was to take a Cyclone and go as far north as we could (Alert is at 82 degrees north) to demonstrate that the sensor in question would work properly, or define when it stopped. If it did not work, we could have requested a design change.”

A former CH-124 Sea King pilot and test pilot on the Cyclone during the early years of the acquisition program, Duval – now retired from the military – was uniquely qualified to lead the northern pilgrimage. Following extensive logistical planning in 2020, the flight was set for summer 2021. However, due to a lack of aircraft availability caused by a high operational tempo, the journey was postponed to the summer of 2022.

It was uncharted territory for the new helicopter.

“The Cyclone had gone on a specific purpose flight permit to 71 degrees north in the Norwegian region while operating with a Halifax-class frigate,” said Duval. “But this was the first time in Canada.”

In 2014, AETE crews executed a similar test program, taking a pair of CH-147F Chinook helicopters to Alert to test navigation and communications systems.

“The challenge (of such a mission) is not necessarily the execution, but the logistical aspect,” said Duval.

He and two other AETE staff members began preparing for the journey in September 2021. Over the winter, they identified the team that would crew the Cyclone, liaised with 12 Wing Shearwater about an airframe suitable for the journey, and worked with 440 Transport Squadron in Yellowknife to coordinate mission support from a CC-138 Twin Otter.

Choosing the aircraft that would make the journey was no simple task. The Cyclone must have a major inspection every 50 hours of flying. Duval and the crew estimated they’d need a full 50 hours of flight time to execute the northern tour. The challenge was therefore to find an aircraft that had performed reliably in the months leading up to the summer flight, but had just been inspected right before the journey. A couple of weeks before the scheduled departure on July 6, airframe 148827 was selected.

“All of that planning happened in a nine-month window,” recalled Duval. “We arranged finances, crew accommodations and identified fuelling locations. Some places in the North only have fuel drums. We had to do some safety analyses to show that we could fuel using drums, while keeping the auxiliary power unit running to keep the aircraft’s electrical and hydraulic systems working. I had so many people helping with the planning. Every two weeks, 15 to 20 people met to advance the file. I was the project officer and the project test pilot as well. It was my job to manage the project – find the right team and delegate as required.”

With the AETE military CH-148 test pilot unavailable for the test window, Duval requested Capt Darren Kroeker from 423 Maritime Helicopter Squadron as co-pilot. He knew Kroeker was interested in becoming a test pilot and would benefit from the experience.

The rest of the crew were volunteers from 423 Maritime Helicopter Squadron at Shearwater. They included Capt Zachary Austin, tactical coordinator (TACCO); MCpl Adam Dickinson, weapon system releaser and avionics technician; and MCpl Matthew Ligon and Cpl Alex Edwards, airframe technicians. The final crewmember was MCpl John Sampson, an aircraft structures technician who accompanied the mission aboard the Twin Otter.

“Let’s get this done”

“We were just happy to leave,” recalled Duval when departure day finally arrived on July 6. “When you’re doing a test like this, there was a lot of work from the maintenance and test flight perspective to get the aircraft ready. The night before, the aircraft was still undergoing testing.

“We departed four hours later than planned, but we were all happy to get going. A lot of us had worked on this for many months – let’s get this done!”

From Shearwater, the crew flew to Schefferville, Quebec, for the first night, with fuel stops at Gaspé, Quebec, and Wabush, Newfoundland and Labrador. On the second day, the CH-148 met up with the Twin Otter in Iqaluit, Nunavut.

“Right now, the Cyclone is still fairly new,” said Duval. “There was a concern that we would require mutual support. If we had a flight emergency in an austere location, there was a concern from a survivability perspective. The Twin Otter’s primary function was to carry 500 pounds of cargo for us, including parts and tools, to mitigate delays. They were also our experts on flying in Nunavut. You can prepare, but there are some lessons you can only learn by doing.”

Upon arrival in Qikiqtarjuaq, Nunavut, on July 8, the group’s careful contingency planning was put to the test. “Heading to Qikiqtarjuaq, we didn’t feel anything abnormal as human beings, but the aircraft’s Integrated Vehicle Health Management System (IVHMS) detected an increase in vibrations on a main rotor blade,” recalled Duval. “We contacted Sikorsky, who is responsible for in-service support, and they said we had to get it fixed before we could go any further.”

Airframe technicians Ligon and Edwards found themselves with a big repair to do on the road, as a pitch control rod linking the main rotor blade to the swashplate needed to be replaced. The part was airlifted by a military Hercules transport aircraft enroute to Iqaluit, where it was met by the expedition’s Twin Otter.

“We got the part on the Wednesday around noon, and they worked four hours to replace it. Then we had to balance the main rotor. The guys I had were super good techs and knew how to do this, with support from Sikorsky. Of course, the beauty of the Arctic in the summer is that it’s always sunny so they could always work by daylight. In just over 24 hours, including 10 hours of crew rest time, they took an unserviceable aircraft and made it serviceable.”

In all, the Cyclone stayed in Qikiqtarjuaq for four days, resuming the journey on July 14.

Lessons learned

Aside from maintenance-related issues, one of the biggest mission planning challenges was fuel availability. The Cyclone’s 350-mile range meant that fuel stops had to be carefully planned in the North.

“For everything up to Clyde River, Nunavut, there were no issues getting fuel from a truck or pumping station,” said Duval. “With the co-pilot, we looked at the airports available along our route and what fuel types they had and how it was delivered.”

Fuel stops following Clyde River forced the crew to carefully plan their routing – the North was in the grips of a fuel scarcity, which complicated matters even further. Fuel for the entire year is normally delivered by barge in the summer; however, this year, the ice around the northern tip of Baffin Island had not broken off. The barge had not yet been able to make the delivery. After Clyde River, Arctic Bay was the only option.

“I had to go into the performance chart of the aircraft and crunch the numbers,” said Duval. “We were cognizant of the maximum headwind we could have and the fuel burn rate we needed to target, as diversion airports along the route were not available. We flew that leg and made it to Arctic Bay. But an hour after we left, the airport issued a NOTAM saying fuel was only available for medical evacuations. We had to come back another way, via Resolute Bay, which was not an optimal route.”

Duval said these were all good lessons to be learned. All the pertinent information that might affect future Wing operations will go into the aircraft flight manual and the standard maneuver manual.

Despite his meticulous planning, there was one thing Duval had not anticipated: the severity of the dust clouds created when the Cyclone was landing on northern runways.

“I had not necessarily realized how much dust we’d create with this aircraft on gravel runways,” he recounted. “When hovering, the rotor downwash lifts dust particles, recirculates them and creates a cloud around the aircraft. It can be very dangerous since it reduces visual references outside the cockpit.”

Upon arrival at Qikiqtarjuaq, for instance, the helicopter became fully engulfed in a dustball. Fortunately, the Cyclone’s automation capabilities allowed the aircraft to enter a hover and wait for the dust to settle.

“Capt Kroeker and I had to decide how to use automation to deal with future landings and takeoffs to mitigate the hazards,” said Duval. “Those lessons we’ve learned will be documented in the test report to update the standard manuever manual.”

The crew reached Alert on July 16. After a couple of days on top of the world, the Cyclone set off on the long journey home. On July 22, the crew made a triumphant return to Shearwater.

“A lot of people were waiting for us,” recalled Duval. “The Wing commander, operations officer, maintenance team for 423 Squadron, pretty much all of the higher chain of command.”

When the aircraft shut down, there was a profound feeling of relief.

“We set out to do something, we came back 16 days later, and we had accomplished everything. We contributed to the expansion of the Cyclone’s operational capabilities.”

An unforgettable journey

Duval called the voyage to Alert an “epic” experience.

“It was epic because this aircraft behaved as I expected it to behave. The people I was working with, including the Twin Otter crew – we had a lot of fun. The scenery was outstanding and the people we met at each of those hamlets accepted us with a smile and tons of questions about what we were doing. All of those things combined, that’s why I use ‘epic.’ There are no words to describe the sum of all those little elements.”

The beauty of the North will always stay with Duval.

“You’re flying with five other guys and you would not expect the beauty of the scenery to be the main point of conversation. Glaciers, waterfalls, high peaks, frozen water, fjords – every 30 minutes or so, it seemed the ground changed. It was bright red, filled with iron, then a cream color, and then darker.”

Duval is the only member of the crew who spotted a polar bear diving below the ice. Muskox, beluga whales, narwhals, and seals were common sights.

Most of all, he will remember the camaraderie of the journey.

“We had super long days of flying and work. There were no complaints from any of the crew. They volunteered to do this, to be away from home for weeks in the summertime to support the mission. They truly believed in the cause.”

Mission accomplished

When the Cyclone and its crew returned to Shearwater on July 22, they had proven the new helicopter capable of operating in the world’s most remote northern reaches.

“Based on the data, the flight control, navigation, and mission systems work properly,” said Duval, although he added there is a long process between analyzing the data and finalizing the compliance that will remove any airworthiness limitations.

“Wherever Halifax-class frigates can go, a Cyclone can go. But we don’t need a ship to operate up North. We can now self-deploy.”

With the Arctic becoming strategically more important, the Cyclone’s expanded capabilities come at a good time.

For Duval, who was heavily involved in the CH-148 Cyclone’s development with Sikorsky, the test results were not surprising.

“I’ve been involved with this aircraft since 2007,” he said. “I know what this aircraft is truly capable of doing from handling to performance, and its mission systems suite. Over the years, the Cyclone has had a lot of bad press. Too often, the media shows the negative side of things and it’s rare that we take the time to showcase a success story.

“I always knew the Cyclone was capable of operating in the Arctic. We just had to prove it. Was I surprised? No, because I know what the Cyclone can do.”

This renews my faith in the capabilities of the RCAF.

Fantastic article on a very underrated, but capable, helicopter.

Amazing journey and exploration spirit!

Looks like an awesome trip. Love seeing the aircraft out there in the real world. I also loved to see these words in the write up, “However, due to a lack of aircraft availability caused by a high operational tempo”. In the end the CH148 turned out to be a great aircraft.

I was fortunate that during my career, I had the opportunity to head to the Arctic two summers in a row. This article brought it all flashing back to me, especially how starkly beautiful the region actually is. Well done to you all for such a professionally organized adventure. And I was not a bit surprised by the results.

Very neat story, nice job.

Would like to point out that within two days of the 50 hour major inspection on the selected for reliability airframe, it went TU in flight.

You can self -deploy, with a C-130 and Twin Otter in tow, and can’t float like the incumbent. Maritime will not be merry time.