Estimated reading time 15 minutes, 29 seconds.

The risks of aviation are well known. Almost any pilot will tell you they bear them because flying is their passion. The same goes for motorsport. So when you mix the two, you might expect to find tales of cut-throat competition between venerated protagonists.

The truth about Formula One air racing is quite different, but is nonetheless a fascinating account of both competition and collaboration among a dedicated few. In more than 65 years, the exploits of its competitors were barely known outside of a desert city in Nevada. In 2013, Jeff Zaltman set out to change that and make the story global. He didn’t know that it would put him at the forefront of a revolution in aircraft propulsion, and lead to collaborations with some of the largest aerospace companies in the world.

Zaltman had visited the spiritual home of air racing at Reno, Nevada, having gained his private pilot license in the same state.

“I became a pilot when I was around 28, kind of on a whim,” he said. “I was in Las Vegas. You get a lot of whims in Las Vegas!”

After witnessing air racing first-hand, he couldn’t understand why it wasn’t more widely known. “I’d seen some of these amazing sports and I thought, ‘Why does nobody know about this?’”

After leaving the U.S. Navy where he had served as an avionics engineer, Zaltman set out to pursue his goal of popularizing airborne motorsport. He settled on the Formula One air racing format after experimenting with a competition of his own design called Aero GP, which he started in 2005.

“With Aero GP, I tried to invent a sport that was audience-friendly, and it was,” he explained. “But it didn’t have that history.”

Formula One air racing had just what he needed.

In the 1930s, “midget racing” was devised, which saw racing planes of that era fitted with smaller engines than was typical at the time.

In 1947, the founding rules were dictated by the IF1 (International Formula One Air Racing Association), which is the authority recognized by the FAI (Fédération Aéronautique Internationale) to govern Formula One air racing.

“Air Race 1 has a global exclusive contract, within which IF1 runs the contest and Air Race 1 owns the rights and promotes the events,” said Zaltman. “It’s a cohesive partnership.”

Up until 2014, IF1 had run races in North America, including Canada and the U.S., which gradually coalesced into a calendar centered on racing at Reno. Zaltman’s plan was to launch an international calendar of races using the IF1 formula. While Formula One air races had previously been run in the U.K. and France, they had never been widely promoted.

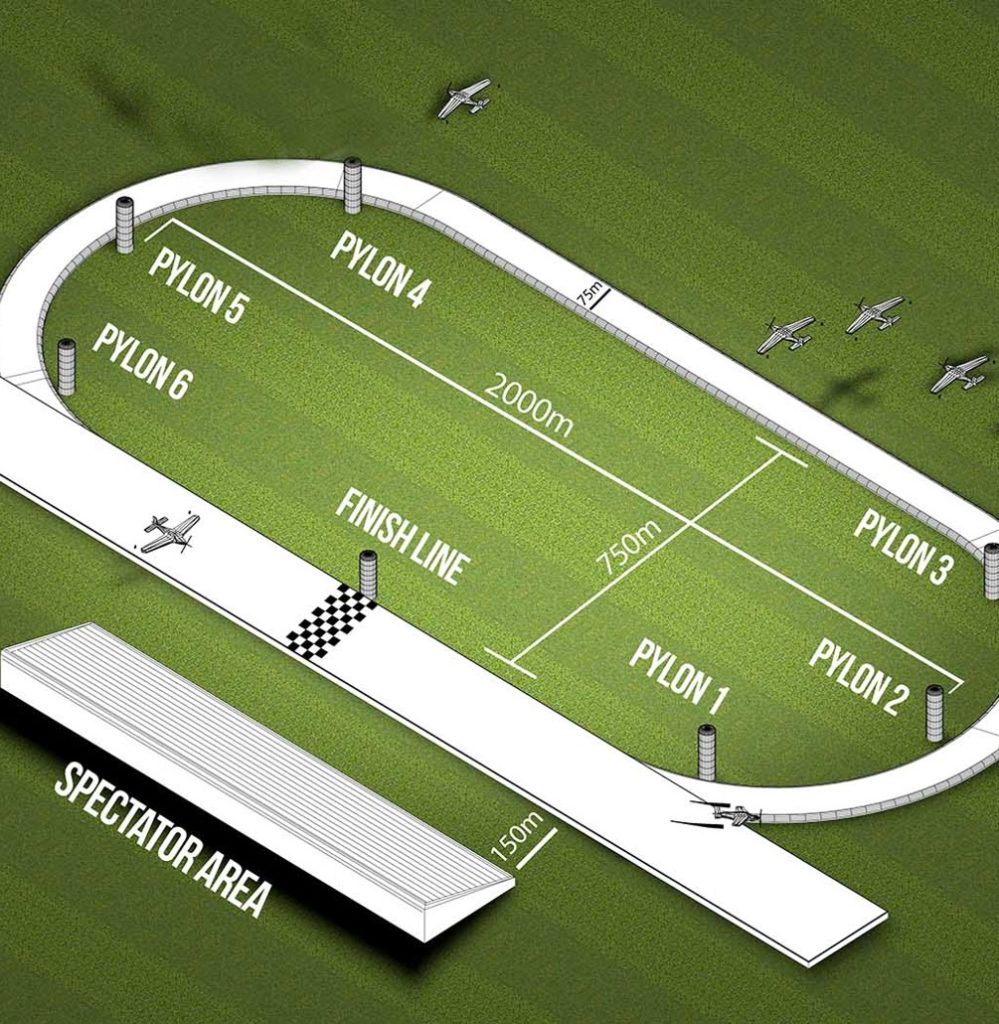

Winning Formula

The standard circuit for a Formula One air race is laid down in the rules, with adaptations referred to as a 3G circuit and a 3.5G circuit — reflecting the load factor flying around the turns at either end of a five-kilometer (3.1-mile) oval circuit demarked by six pylons. A “home pylon” in the center of one of the straights denotes the start/finish point at which racing begins, but the competition gets underway from a standing start on the runway.

“It’s the only air race in the world which always has a standing start, so they line up on the runway in places chosen according to qualifying position,” explained Zaltman. “There’s no racing prior to the home pylon, but planes inevitably pass each other because of their intrinsic properties.”

The pilots jockey for advantageous positions in three dimensions from the outset, as some accelerate faster and others have higher top speeds — despite all being powered by a standard Continental O-200 engine.

“The O-200 is a 100-horsepower engine, but for a short period of time you can get a lot more out of them,” said Zaltman. “But it’s really in the aerodynamics where the teams gain the edge. The aircraft were built solely to race, not repurposed from another mission.”

The race format itself already worked as an international championship. Zaltman described it as “accessible and exciting.” However, there were challenges taking the competition out of Reno and deploying it across the world.

“The first Air Race 1 event was in Spain and included French, British, and U.S. teams,” said Zaltman. “There were a lot of briefings and brainstorming sessions, because everyone was out of their element. That’s where my Aero GP experience really helped because I knew what the hurdles and sensitivities would be.”

The aircraft are shipped to each event in containers, so the first job after arriving is to build and test them.

“Imagine a hangar with up to 30 airplanes being put together, there’s just parts everywhere,” said Zaltman. “The teams know what’s going on, but it looks like chaos. And out of a pile of parts, they form these airplanes.”

Only eight aircraft can be on the track at a time — racing at speeds of over 400 km per hour (250 miles per hour) just 10 meters (33 feet) above the ground — so competitors move between groups during qualification. Up to five races of eight to 10 minutes each are flown each day of a race weekend, and only the fastest aircraft fly in the final. Get a penalty early on, and you may find yourself with a lot of work to do to fly in the final.

“You can’t just be first; you’ve got to be fast,” explained Zaltman.

International Appeal

The Air Race 1 teams’ familiarity with the formula was a vital ingredient in delivering such high-workload events across the globe, but this advantage could have easily been offset by their dependence on the infrastructure that they were used to at Reno.

“Things that would be easy back home are suddenly a challenge. Where do we get a part? There’s no aviation shop with parts just around the corner,” explained Zaltman.

But what might have been lacking in spares and support on location was made up by the teams — who seemed to prioritize the greater good of competing, even above winning.

“There were two occasions where aircraft were damaged in transit and were unflyable,” said Zaltman. “They would have stayed that way were it not for the other teams helping them out.

While the teams were prepared for the international spotlight, getting a fanbase to provide that attention would depend on making the events attractive to local audiences.

Elements of the event were tailored to reflect the national culture of the host city. The French team’s aircraft was flown by a pilot who lived in Bangkok, and so for the race in Thailand they painted their aircraft in a nationally traditional design.

“We wanted to make it their event, so that it was relatable even without a Thai pilot,” said Zaltman.

While localizing the events was a challenge, finding stories that appealed to international press coverage proved much less difficult.

“The people in the race teams are from all different backgrounds, which tells the story of the allure of aviation,” said Zaltman. “They’re not polished, manufactured mannequins that you put up on a stage,” he explained. “So that creates a lot of stories and allows an emotional connection that cuts through culture, background, and nationality.”

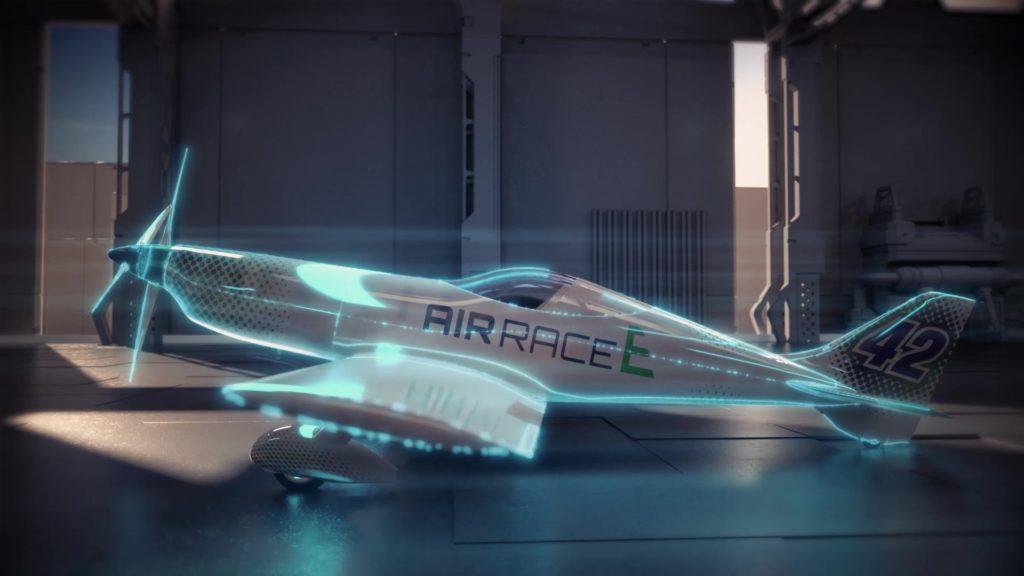

Air Race E

With several Air Race 1 events per year across several continents, Zaltman began to attract the attention of manufacturers keen to promote their own aviation vision.

“I kind of became known as the Air Race guy, and there were a few electric aircraft manufacturers who were asking me about the potential of racing,” he said. “But the aircraft were a long way away from being fully developed. It didn’t really make commercial sense.”

Over time, these proposals became more tangible, but most were framed around one aircraft supplier providing all the teams with the same aircraft.

“The proposed model didn’t do much for the technology,” explained Zaltman. “But when it became clear that we could convert experimental airplanes to electric propulsion. I realized we already had a platform that would work, we had everything apart from the propulsion.”

Zaltman had what he believed was a workable concept, but soon found himself racing against the clock.

“Once I realized that this could be done right now, I knew we had to get it out there,” he said. “So, we announced it before we really knew how we were going to deliver it.”

Air Race E was announced in 2018, and within a few months, Zaltman was talking to Airbus and other partners — including the University of Nottingham in Great Britain. Meanwhile, he was still learning about the technology.

“To confess, I wasn’t really passionate about the electric concept; it seemed like something the next generation would be thinking about,” he explained. “I haven’t been a sceptic, but I wasn’t entrenched in it. Now I do see it as the future and most of the aerospace industry seems to feel the same way.”

There are now 17 teams registered for Air Race E, all at different stages of readiness. Roughly half are retrofitting an existing aircraft, and the rest have a clean-sheet design — even building components of the power train.

In mid-October, the Nordic Air Racing Team completed a ground test with its electric aircraft – a specifically converted Cassutt IIIM formula race plane — prior to carrying out the first-ever electric race plane flight later this year. This is all in preparation for the inaugural season of Air Race E.

For the upcoming Air Race E, it was originally planned that the aircraft and the power plant design would be completely up to the teams, in what has become known as the “Open Class.” But in early in 2021, two new classes were announced that will be introduced over time.

The “Performance Class” will have a bespoke powertrain, which will be fitted to the team’s own aircraft, leaving optimization of sub-systems and cooling systems as the primary means to increase performance.

Most recently announced will be the “eVTOL Class,” which Zaltman said is still evolving, but has already involved dialogue with proposed manufacturers.

It is likely to be some time in the future before the first crewed eVTOL race. Along with the rest of the world, Air Race E suffered significant challenges in 2020, and the first Open Class race is expected in 2023.

Air Race E organizers are evaluating several host cities for their first year, but Zaltman did not allude to a specific location. With the company registered in Dubai, and with the United Arab Emirates keenly pursuing both aerospace technology and sustainability, an event in that country seems a strong possibility. Its brand would certainly seem attractive to potential Air Race E fans.

“The audience is likely to be younger, more conscious about sustainability and more urban,” said Zaltman. “At the same time, we expect them to be less nostalgic and more technology-driven.”

Both Air Race 1 and Air Race E have cultivated a broad appeal with a fanbase straddling motorsport and aviation, but which sits distinct from airshow crowds.

Zaltman’s aim is to build Air Race E to similar levels of audience engagement, but for now, he is realistic about the fact that the main interest is from the aerospace and technology sector.

“At the moment, we are focused on technology partners who can get something out of the sport from an engineering point of view” he said. “These companies want to see what the teams can do with their product and showcase that they are part of the early days.”

Zaltman is aware of the challenge of doing this while maintaining the grass-roots appeal of the Formula One format.

There’s a paradox between the need to retain the character and the legacy of air racing, and produce a product that sells tickets, grows an international fanbase and can even help develop new technologies. Striking the right balance will require both business acumen and passionate dedication.

“We’ve had commercial success,” said Zaltman. “But a lot of people have had to roll up their sleeves to make it work.”

For all the risk in aviation, there must always be passion to match. But it is imparting that passion into a fanbase that will turn the midget racers of Reno into an international success.