Estimated reading time 13 minutes, 28 seconds.

Before making a name for itself in the aerospace market, Bombardier started out as a rural snowmobile maker in 1942, and eventually produced subway cars, trams, and commuter and high-speed inter-city trains. It expanded into aerospace decades later with the acquisitions of Canadair, De Havilland, Learjet, and Short Brothers. By 2014, it was the world’s third largest aircraft manufacturer and the world’s leading producer of railway equipment. That year, its consolidated revenues peaked at US$20 billion, and its 74,000 employees were at 80 sites in 28 countries. The company also had numerous aircraft models being developed concurrently.

The corporation’s engineering and cash resources became severely stressed. As a result, aircraft development and certification schedules were pushed out, and its financial performance deteriorated. Despite the Learjet 85 program being cancelled in October 2015, it became evident that more difficult decisions were required.

A series of significant divestitures followed. They included the CL-415 amphibious aircraft program to Viking Air (October 2016); the Business Aircraft division’s training activities to CAE (March 2019); the Q Series regional airliner program and De Havilland trademark to Viking Air (June 2019); the C Series mainline airliner program to Airbus and Investissement Quebec (February 2020); the CRJ regional jet program to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (June 2020); and the aerostructures business to Spirit AeroSystems Holdings (October 2020). In February 2021, Bombardier announced that its final Wichita, Kansas-built aircraft, a Learjet 75 Liberty, would be delivered by year-end.

That was then.

Today, Bombardier is focused on one business: The corporate jet market. It currently produces five models — two for the medium business jet niche (the Challenger 350 and Challenger 650), and three for the large aircraft niche (the Global 5500, Global 6500, and Global 7500). Prices for a fully completed airplane range from approximately US$27 million for a new Challenger 350 to about US$75 million for a Global 7500.

The purchasers of medium and large business jets tend to be corporations, families, governments and fractional ownership programs. The latter serve customers who don’t wish to purchase an entire airplane. They offer from as little as a 1/16 interest (representing 50 hours of annual flight time) to as much as a ½ share (representing 400 hours). For those requiring even less time, “jet cards” are available that enable a customer to purchase 25 to 50 hours that can be used over 24 months.

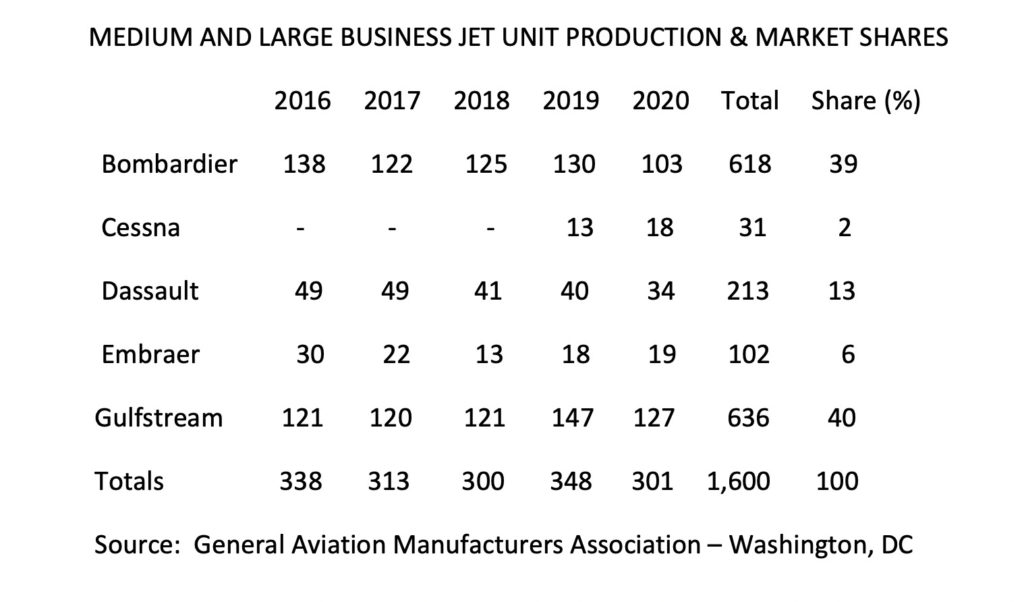

Five OEMs serve the medium and large business jet niches. Besides Bombardier, they include Textron Aviation’s Cessna unit, Dassault Aviation, Embraer, and Gulfstream Aerospace. Annual production statistics for the past five years provided by the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (presented in the table below) combine the medium and large niches.

The data shows that during that period, 1,600 aircraft in the medium and large categories were delivered. Bombardier and Gulfstream were the two major players, each with about 40 percent of the market. Dassault had a 13 percent share, while Embraer and Cessna obtained six percent and two percent shares, respectively. (Cessna entered the competition in 2019 with its Citation Longitude in the medium category.)

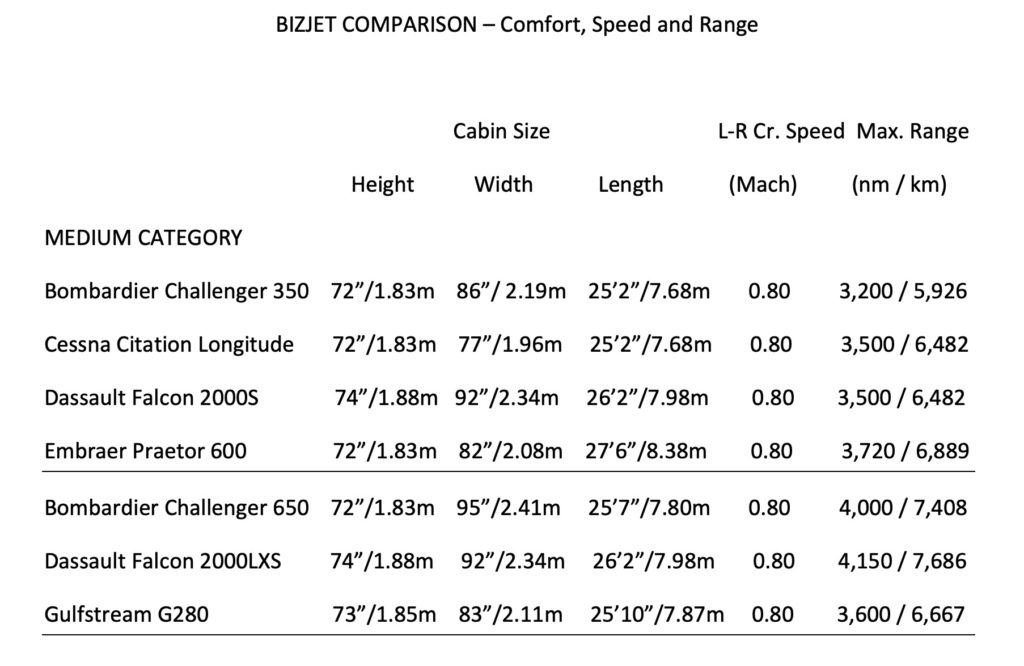

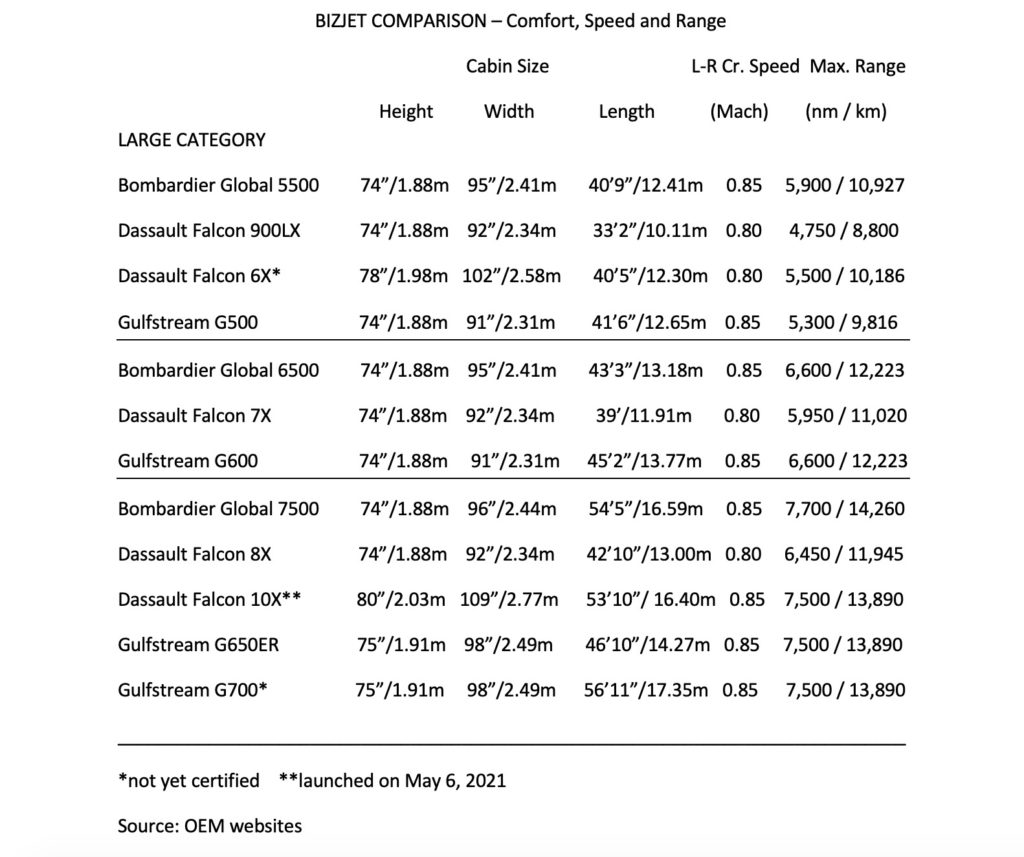

Extensive performance and detailed specifications pertaining to these aircraft are available on the OEMs’ websites. In order to get a basic idea of how these models compare, Skies assembled two tables (below) based on three popular criteria used by buyers to evaluate corporate aircraft – cabin size, speed, and range.

Now, let’s take a look at Bombardier’s product portfolio.

The Challenger 350 is the enhanced variant of the Challenger 300 (457 built), and has proven to be popular with corporate flight departments and fractional owners. Approximately 375 have been delivered.

The Challenger 650 is the seventh generation of the Challenger 600 Series family (999 built). In addition to its traditional corporate role, the aircraft has been selected for special missions including air ambulance work and military surveillance. Approximately 110 have been delivered.

The Global 5500 is an upgraded version of the Global 5000 (238 built). It boasts new Rolls-Royce Pearl 15 engines and redesigned wings that provide a class-leading range of 5,900 nautical miles.

The Global 6500 is the latest iteration of what was successively the Global Express/Global Express XRS/Global 6000 (641 built). With new Pearl turbofans and a reworked wing, the Global 6500 can fly 6,600 nm at Mach .85 — a 10 percent improvement over its predecessor.

And last, but not least, the Global 7500, which was originally the Global 7000. It received its new name after better-than-expected range capability was achieved during the certification process. With a new wing and a pair of GE Passport engines that can produce almost 38,000 pounds of thrust, the Global 7500 can fly 7,700 nm at Mach .85. That is the longest advertised range capability of any purpose-built business aircraft. Most of the first 50 units delivered have gone to experienced Global operators.

The Global 7500 will have two direct competitors: The Gulfstream G700, which is working towards certification with an entry into service expected in late 2022; and the recently launched Dassault Falcon 10X, which is expected to enter service in 2025. Dassault’s entry reflects the level of demand at the upper end of the corporate jet market.

Looking Forward

The aforementioned financial underperformance has left the company with a debt-ridden balance sheet; this has caused credit rating agencies to assign undesirable grades on Bombardier’s debt. Financial stability is not only the key to survival, but also to retaining and attracting customers. Bombardier has a plan to significantly improve its current situation by growing revenues, improving operating margins, and gradually retiring debt.

At March 31, 2021, Bombardier had an order backlog of US$10.4 billion that reflected customers’ confidence in the company’s products. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused corporations and families to investigate flying solutions that best meet their needs. Fractional ownership operators have reported increased demand for their services.

While selling new aircraft will remain the significant source of Bombardier’s revenues, it is looking to increase its participation in the aftermarket service industry. During 2019, the business of maintaining Bombardier corporate jets generated about US$3.2 billion. Bombardier captured roughly US$1.2 billion (38 percent) of that market and is working to increase its share to 50 percent (US$2 billion) by 2025. Expanded facilities in Berlin, Singapore, London, Melbourne, and Miami should provide the capacity required to achieve that goal. During 2020, aftermarket business represented about 18 percent of Bombardier’s top line. The company forecasts its share will grow to 27 percent by 2025.

New aircraft sales and aftermarket activities are expected to boost Bombardier’s top line from US$5.6 billion in 2020 to US$7.5 billion in 2025 – representing a five percent CAGR.

Operating Expenses

Bombardier is looking to reduce its annual operating expenses by approximately US$400 million by 2023. This would be achieved by a 30 percent reduction in its manufacturing footprint (US$50 million); a 10 percent reduction in procurement costs (US$125 million); and improved labor productivity with a reduction of about 1,000 full-time employees (US$150 million). As well, another US$75 million of annual savings are being targeted.

As the Global 7500 production rate increases, improved efficiencies are being realized, too. For example, the combined cost of the materials and the employees needed to produce the 50th example were approximately 40 percent less than that of the first aircraft. Bombardier forecasts that the 100th example will cost about 20 percent less to build than the 50th unit.

These savings are coming from manpower productivity, engineering standardization, and lower procurement costs.

Improved Balance Sheet

With these increased revenues, operating cost reductions, and improved efficiencies, Bombardier forecasts that its earnings before interest, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) will be US$1.5 billion in 2025 — up from US$200 million in 2020. More importantly, the company expects to generate US$500 million of free cash flow in 2025. This, combined with proceeds from recent divestitures, should enable a significant improvement in the strength of its balance sheet through debt retirement.

Now that senior management is focused on fewer moving parts, Bombardier is positioned to enhance its earnings performance and improve the stability of its balance sheet.

In the medium-term, Bombardier may see the need to refresh its Challenger 350 and 650 models that entered service in June 2014 and December 2015, respectively. Longer term, it remains to be seen when another clean-sheet aircraft might be developed. Given the engineering talent and capital required for such an undertaking, Bombardier may work with industry partners on such a project.

Leading the turnaround effort is Eric Martel, who was appointed president and CEO of Bombardier in March 2020. Martel is confident in Bombardier’s strategy, stating: “Business jet utilization rates are nearly back to 2019 levels, global wealth is growing, and demand for large-cabin and long-range aircraft — such as the flagship Global 7500 — remains positive.”

With attractive products, an impressive order backlog, and increasing demand from both established and new customers, Bombardier promises to be an interesting company to follow.

In the meantime I have lost quiet a bit of money…….., believing that Bombardier is becoming the 3. biggest supplier in the aviation industry…..! Keep on dreaming.

Over the course of almost 40 years I have been a banker to, an unwritter of, and an investor in … Bombardier. I’d sooner donate money to the WE Charity (irony intended) than ever again invest in or believe their prattle.

The trifecta of reduction of 30 % reduction in manufacturing cost (unrealistic) reduction of 10 percent in procurement (optimistic) and increased efficiency by volume production (realistic). Not a lot of confidence in the family though. Wish they would sell.

The outlined strategy sounds overly ambitious. But If they can achieve even half of this then they will rapidly return to financial health. Hopefully they will

Dear Sir/Madam,

I hope this email finds you well, I would like to send you a press release. I will appreciate if you can email me your email address.

thank you very much

lost more than $ 100,000 SO FAR with that crazy plan of AB220…….

Bought at 22 cents/ share.

When to sell??