Estimated reading time 7 minutes, 56 seconds.

This article was originally published in the October/November issue of Skies.

Mark Twain once quipped: “A man who carries a cat by the tail learns something he can learn in no other way.” He was addressing the value of direct experience in gaining knowledge versus theoretical study in the classroom. It’s all fine and good to know theory, but when the rubber hits the road — or more precisely, when the wheels are in the well — real learning starts right away. This is especially true in IFR flight.

It’s particularly relevant as we move from balmy summer skies to the capricious nature of winter weather, along with increased nighttime hours that add to the demands of IFR flight. But the fun doesn’t stop there. A myriad of visual illusions and the peculiarities of human physiology all can contribute to a challenging time in the air.

Let’s start with the complicated process of vision involving the eyes and the brain.

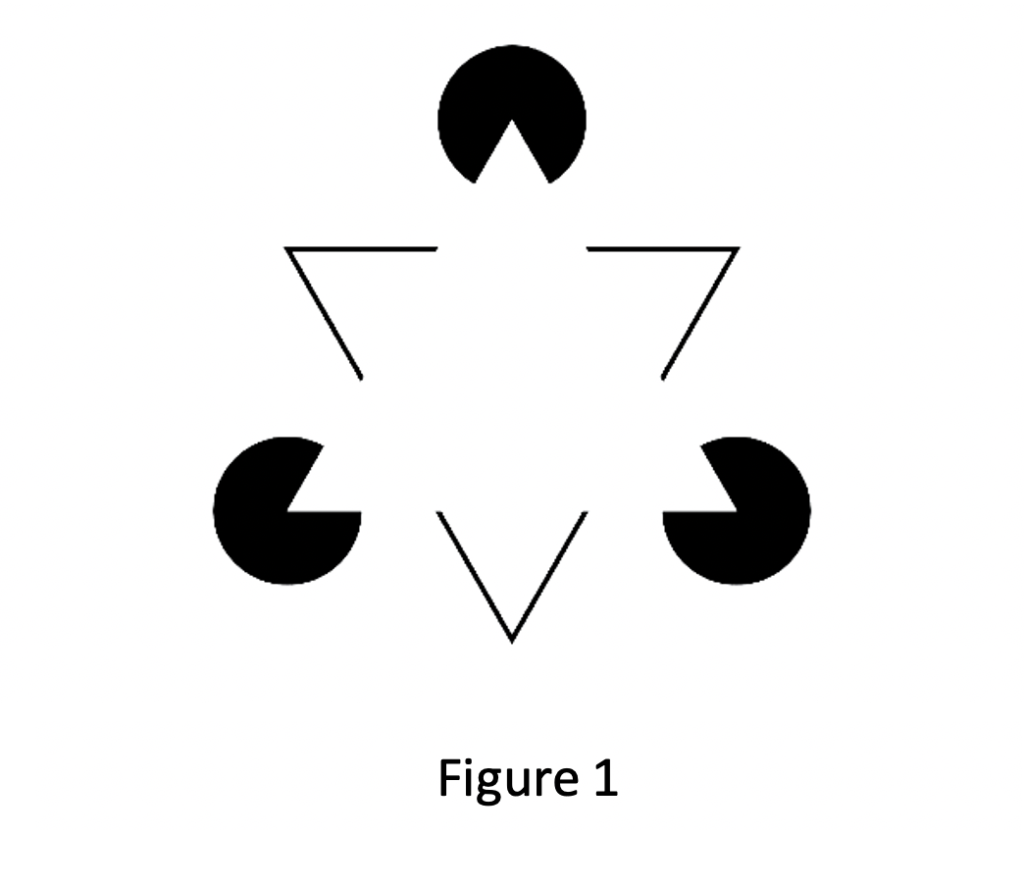

Our brains are trained to fill in gaps between shapes and lines and perceive blank space as objects even when there aren’t any. Look at Figure 1, a well-known example of the Gestalt Effect. There is a nonexistent triangle that is formed by the edges of the three Pac-Man circles — a direct result of the brain’s ability to generate whole forms from groupings of lines and shapes.

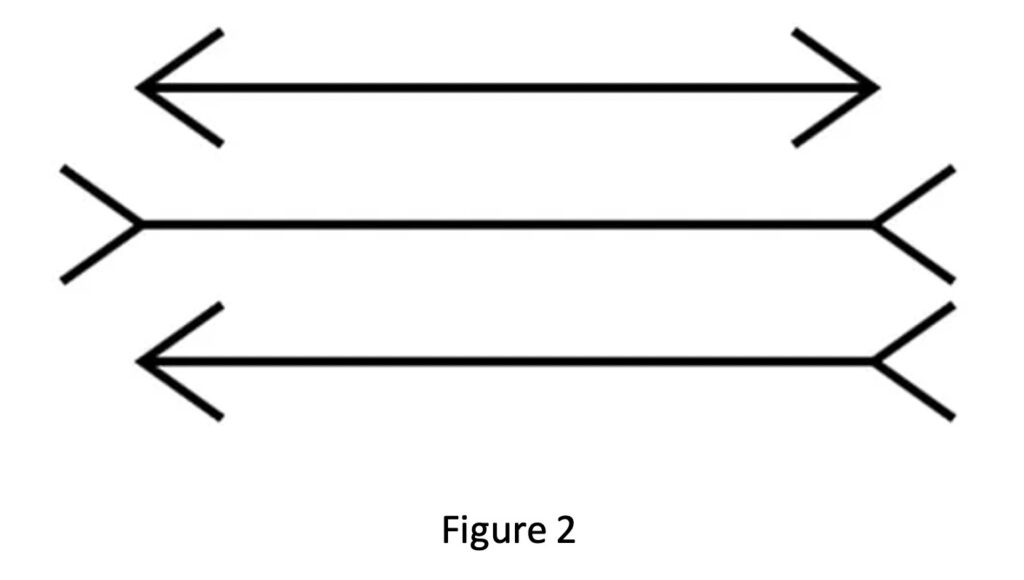

Figure 2 is an even simpler example of false perceptions. Why is it that the three horizontal lines appear to be different lengths, when they are actually the same? Good question. And adding to the mystery is the fact that experts do not always agree on what causes such illusions.

The point is, what we perceive is shaped by experience and not merely a function of sensory input. What you ‘see’ is not necessarily what is there because of the way the brain processes visual information. It is knowing that you are susceptible to being visually fooled that can help you compensate for visual illusions you may encounter in flight.

But enough theory already; let’s go flying! A very common visual illusion occurs when you fly from a wide runway to a much narrower runway. During the landing phase at the latter, there is a tendency to misjudge the actual height above the runway (i.e., during flare and roundout you may think you are higher above the runway than you actually are because you are awaiting the peripheral visual cues of the runway edges to be at the same angle as the wider runway). This can result in a late flare and a ‘thumped-on’ landing.

Similarly, if the runway is much wider than what you are used to, there is a tendency to flare too early. Both situations are magnified when shooting an IFR approach to minimums, where the time between first seeing the runway and touchdown may be a matter of seconds.

Another visual illusion that can make for a bad day at the office occurs when you are departing a runway at night that is higher than the surrounding terrain. Once airborne, the pilot may confuse clouds as the horizon, or surface lights as stars.

The latter occurred to me some years ago when I was asked to be a safety pilot on a Cessna 310 with the company sales rep who had just gotten his IFR rating.

We were making a series of visits across the Prairies, and on one of the stops we picked up his son who had just received his private pilot license. The sales rep asked if his son could occupy the right seat, to which I agreed.

We departed IMC in the dark with a low overcast sky, and there was a small subdivision in a nearby valley just after takeoff. As a prudent measure, I was closely monitoring the takeoff from the back seat. Sure enough, right after the wheels came up, we started into a shallow descent; the sales rep wasn’t keeping an eye on the attitude indicator, perceiving the subdivision lights as stars.

Needless to say, I quickly ‘suggested’ we raise the nose to a correct climb attitude.

Visual illusions are most significant when transitioning from being on instruments in IMC to visual references in VMC. The good news is that you can minimize or negate their effects by establishing and following some good habits.

In your pre-flight planning, review the runway length, width, and slope as well as the surrounding environment so you can anticipate any possible visual illusions.

On an IFR departure, ensure you have a positive rate of climb and then go ‘on the dials’ rather than being 50/50 on instruments and looking out the windows.

On arrival, complete your pre-landing planning and checks well in advance so you can focus on final approach and landing. If an approach slope indicator is available, ensure it is turned on and in operation. Staying on the glideslope can counter any visual illusions you may experience.

A last word: If you find yourself rushed and behind the eight ball on approach (who hasn’t been there?), execute a go-around rather than trying to salvage a poor approach. It’s better to be very, very safe, than very, very sorry.