Estimated reading time 15 minutes, 47 seconds.

On the morning of July 10, 2018, Taquan Air Service slammed into an area in Southeast Alaska known as Jumbo Mountain. Six passengers were seriously injured. The part 135 charter was on a 45-minute flight in a de Havilland Otter from Steamboat Bay to its home base of Ketchikan. Passengers would later tell investigators they passed in and out of clouds and fog almost from the minute they departed, with one pilot-rated passenger commenting it was “barely VFR [visual flight rules].”

As the investigation commenced, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found multiple problems with the on-demand and commuter operator, starting with the fact that its director of operations (DO) lived more than 750 miles away in Anchorage, where he worked in the same capacity for another part 135 operator. Investigators noted “inadequate operational control procedures . . . the exercise of operational control by unapproved persons . . . inattentive and distracted management personnel, and a loss of operational control within the air carrier.”

They also found something else: Jumbo Mountain was another crash involving a member of the Medallion Foundation.

Founded in 2001, the Medallion Foundation was a non-profit Alaskan safety organization established by the Alaska Air Carriers Association (AACA), a state industry group, to “improve pilot safety awareness” and “reduce air carrier insurance rates.” From the very beginning, however, it was also perceived as a positive economic tool. AACA executive director Karen Casanova explained to an Alaska Senate Committee in November 2001: “[AACA members] feel it is the cornerstone to providing safer air transportation for the traveling public. It can also be used as a marketing tool now with declining revenues.”

In 2002, Senator Ted Stevens facilitated an initial $3 million Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grant that would be followed by $19.5 million more from the agency over the next 17 years. As the cash flowed and accolades poured in, there was only one problem: no one could be certain Medallion’s approach was working.

Per its FAA funding agreements, Medallion’s purview included many initiatives including the purchase and maintenance of flight training devices, passenger safety awareness campaigns, and management of the Aviation Safety Action Program. The most significant by far was the Star and Shield safety program which focused on five key areas: CFIT (Controlled Flight Into Terrain) Avoidance, Operational Control, Maintenance and Ground Service, Safety, and Internal Evaluation.

Medallion members were awarded Stars upon completion of each unit and then, after five Stars, became eligible for a Shield. (The Star program eventually included two additional categories.) Independent of FAA oversight, the program was geared toward fostering a corporate safety culture but was designed with the public in mind. As executive director Jerry Dennis stated in 2003, the awards “advertise a commitment that the operator has toward enhancing safety.”

Acclaim for Medallion from state and federal officials came hard and fast. “This is something that truly saves lives,” said FAA Administrator Marion Blakey the same year. Stevens was also effusive in his praise, declaring early on: “If they’re not in the Medallion program, then don’t get on the aircraft.” (This statement appeared in ads for years.)

In 2006, the State of Alaska began requiring participation in the Star and Shield program to bid on Medicaid travel contracts. And in 2013, Governor Sean Parnell told the Chamber of Commerce, “If you’re traveling on a Medallion-certified air carrier, you are traveling with people who have been trained above and beyond the minimum.” But again, no one was checking Medallion’s accident track record.

According to FAA documents acquired via the Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA), Alaska Airlines was the first Medallion member, on Jan. 3, 2002. (Unfortunately, the FAA has no complete record of annual members or Star and Shield holders. FOIA documents and extensive online research provide what is likely an incomplete membership list.)

Searching the NTSB database for all accidents involving Alaskan part 135 operators between January 2002 and Dec. 31, 2019, a total of 459 accidents is found. (This includes accidents that occurred while flying under part 91 rules, such as during positioning or training flights.) There were at least 149 accidents for Medallion part 135 carriers in that period, or 32 percent of the total. Medallion also represented at least 37 percent of total fatalities in those accidents (52) and 43 percent of total serious injuries (45).

The NTSB did not formally include Medallion in an investigation until 2013. That year, at least nine Medallion part 135 operators and two part 121 airline operators had accidents, causing six fatalities and nine serious injuries. Additionally, the Alaska State Troopers, a part 91 CFIT Star recipient, crashed a helicopter while on a search-and-rescue mission; all three onboard were killed when the pilot flew into deteriorating weather and lost control of the aircraft. When NTSB investigators questioned Medallion after that accident, executive director Gerald Rock spoke in generalities, returning to the familiar line that their membership chose “to operate above and beyond the FAA requirement.” Sometimes, he concluded, “pilots just make mistakes.”

In May 2016, Alaska Flight Standards Division manager Clint Wease issued a letter to air carriers statewide addressing a series of devastating part 135 CFIT accidents over the previous 12 months. After providing safety recommendations, he advised carriers that Medallion “can help guide you in developing systems, policies, and procedures to prevent CFIT accidents.” He did not mention that the worst of the cited accidents involved Medallion carriers, and later acknowledged to NTSB investigators that the letter could have been “interpreted as an endorsement of Medallion.”

In October 2016, Medallion Star carrier Hageland Aviation crashed enroute to Togiak, killing the three people onboard. The accident prompted the NTSB to hold a public investigative hearing in Anchorage the following August (by then Hageland had received its Shield). During the hearing it became clear the annual Star and Shield audits Medallion conducted of its members were exceedingly narrow in scope. They “only capture one single point in time,” said deputy director Deb Walker.

A former auditor had made a similar point when interviewed two months earlier. He told investigators about auditing a tour company in December 2014 when only the DO and chief pilot were working. The operator suffered a multiple fatality crash the following summer but, he said, “there was no way an auditor would have caught what led to the accident.”

The Togiak investigation provided extensive examination of Medallion’s methodology, as investigators explored what Medallion and the FAA did to measure a program’s effectiveness. In an interview summarized by NTSB investigators, Rock said “Medallion looked for the existence of policies and procedures, not effectiveness.” He further stated “it was a carrier’s program, and the carrier should be looking at their accident rates to determine if their program was effective.”

Walker similarly told investigators that “Medallion had no measurable criteria for the effectiveness of training an operator conducts. It was up to the operator to verify the effectiveness of the training.”

For his part, Wease stressed to investigators that the FAA’s sole authority with Medallion was to verify it “was doing what their agreement says they’ll do.” The FAA did audit Medallion, but only to ensure it complied with the memorandum of understanding “rather than the quality of the Medallion programs.”

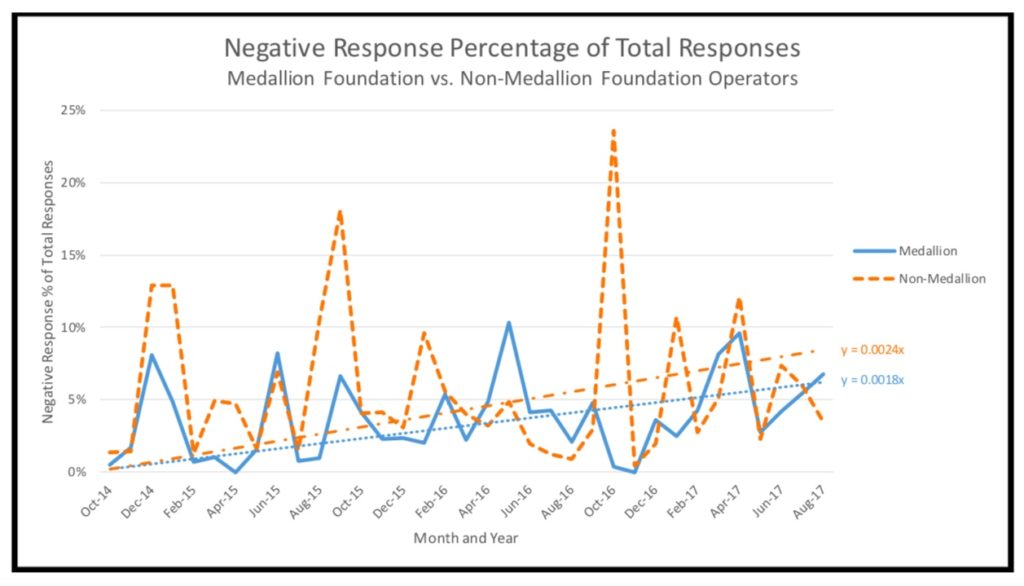

In February 2017, the FAA had submitted a formal report on Togiak to the NTSB which included a section on Medallion. Citing “a locally maintained FAA database that contains NTSB data along with localized incident, occurrence and other information collected by the FAA,” the agency designed a graph showing that Medallion carriers had a lower rate of increase in incidents and accidents between 2001 and 2017 than non-Medallion carriers.

In a second data set it analyzed positive and negative responses from FAA inspectors via its Safety Assurance System Surveillance Data and asserted that negative responses on certain safety terms were at a “lower rate of increase for Medallion Operators than non-Medallion Operators.”

The FAA did not provide its source data with the report and further, its descriptive language suggested that if a carrier dropped its membership (or went out of business), prior to Sept. 1, 2017, it was not considered part of the Medallion data even if it was a member at the time of accident. The agency’s discomfort at quantifying Medallion’s impact on aviation safety was clear then and also when Wease was similarly circumspect during the hearing. When asked how the FAA evaluated the Medallion Shield program, he responded in part, “No, we don’t have hard numbers. But do we know that they’re a key element in reducing accidents? Absolutely.”

After the Togiak crash, accidents involving Medallion carriers continued to occur, including Taquan Air’s collision with Jumbo Mountain. In an August 2018 meeting between Medallion administrators and the FAA, the foundation’s frustration spilled over. Medallion assailed the NTSB for claiming it was “not effective” and decried reduced FAA funding. By February 2019, Rock’s correspondence seeking financial support from the FAA became increasingly desperate.

Then, in May 2019, Alaska made national news when Taquan Air was involved in a midair collision near Ketchikan, killing six and seriously injuring nine. One week later, both the pilot and passenger were killed when a scheduled Taquan flight crashed on landing in Metlakatla harbor. That pilot had only 1,623 hours of total time, and less than 30 hours on floats.

Rock reached out in July to the FAA’s acting administrator, lamenting the decrease in requested funds for the next fiscal year. He claimed a “lack of understanding” about Medallion and threatened to close the foundation. In the FAA’s response, executive director of Flight Standards Rick Domingo affirmed the proposed funding amount while making clear the goal for several years had been Medallion’s self-sufficiency. Further, he said the agency needed “to justify the financial support with quantifiable data for impact to Safety by the Medallion Foundation.”

On Sept. 15, 2019, Medallion closed.

In his NTSB interview on Togiak, Wease had referred to Medallion as a “brand.” While separately insisting that carriers “own their accidents” and “hold pilots accountable,” he bemoaned that “the industry might lose confidence in Medallion if they were tied to a carrier’s accident.”

But from the very beginning, and with no effort to prove their supposition, the FAA and Medallion purposefully linked air carrier safety to participation in Medallion; that message continues to resonate. The Taquan Air Service website still proudly declares it “has been a Five Star-Certified Medallion Shield Carrier since 2008, signifying the airline has exceeded the FAA’s safety requirements.”

The final reports on the company’s most recent crashes are expected this year.

I was a Medallion Foundation auditor and quit after seeing how poorly the company was run with the likes of Deb Walker and Gerry Rock. They had no interest in safety or real audits. They were primarily interested in having the FAA rent Gerry’s building , taking vacations in Hawaii, and getting as many members as possible signed up and star rated whether they qualified or not.

The Rocks scamed a contracter out of money Anna rock stole money from our company

Does anyone know what happened to the simulators?

Several of the simulators ended up with Civil Air Patrol and are available to their members. The rest of the ones that work are at Merrill Field.

Is there anyone out there that still has the Alaska airport “Wind Charts”? I think that’s one product of their program that helped, and I’d love to have a copy if they still exist. If anyone knows of a current source of these charts, i’d be forever in your debt to get a copy.