Estimated reading time 14 minutes, 22 seconds.

Editor’s note: Lola Reid Allin is a writer, photographer, adventurer and commercial pilot based in Belleville, Ont. This is part 1 of a 5-part series by Lola about the under-representation of women in commercial aviation.

In the 40 years since my first flight lesson, the world has changed. Information floods traditional and social media about women enrolled in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) programs — considered avant-garde or non-traditional choices by previous generations — and their success in these fields.

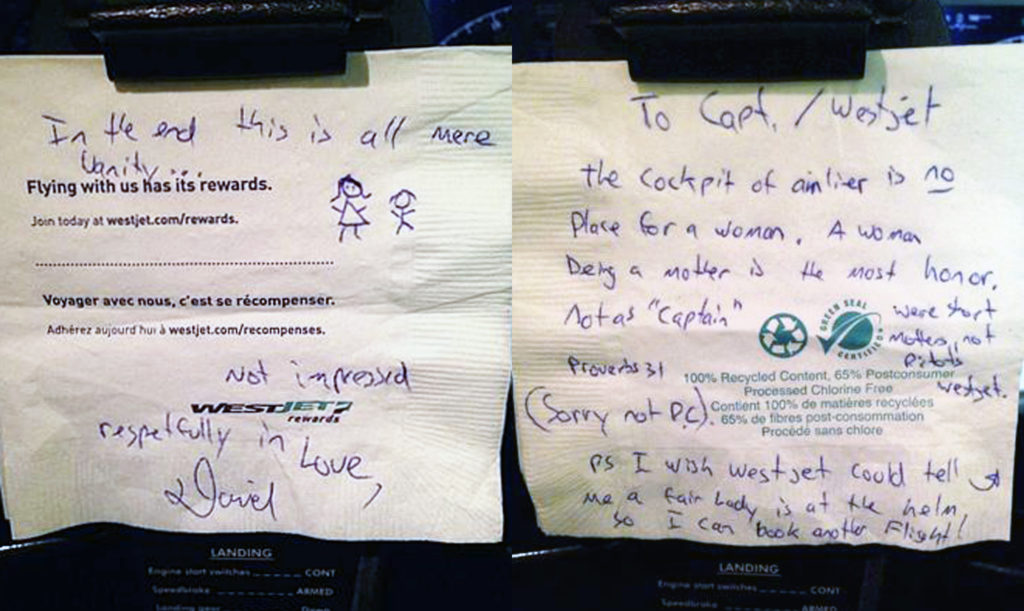

Bolstered by human rights legislation and the understanding that biology no longer determines destiny, I felt certain 21st century female pilots would be basking in a milieu of acceptance — until I read the following note, hastily scratched on a serviette by an airline passenger.

“To Capt./Westjet, The cockpit of airliner is no place for a woman. A woman being a mother is the most honor, not as ‘captain.’ We’re short mothers, not pilots, Westjet. Proverbs 31. P.S. I wish Westjet could tell me a fair lady is at the helm so I could book another flight! In the end this is all mere vanity… Not impressed. Respetfully in love, David.”

A flight attendant presented the serviette to Captain Carey Steacy, who photographed and posted David’s judgment on Facebook (March 2014).

Captain Steacy’s reaction, impossible in the decades before social media, was brave. While the “Me Too” movement has encouraged women to reveal damaging personal experiences and form solidarity, the challenge of speaking out remains daunting. Many women hesitate to reveal personal injustices or sexual harassment perpetrated by colleagues and employers, fearing job loss and social repercussions, in a culture of shaming that often blames the female victim instead of the male perpetrator.

To connect with more female pilots, I joined the Canadian Chapter of Amelia Earhart’s 99s and two Facebook groups (Ladies in Flight Training/LIFT, and an invitation-only group exclusively for female pilots). Via email, I contacted the International Society of Women Airline Pilots (ISWAP), Women in Aviation (WAI), four Canadian air carriers, and a European carrier to ask if any of their female pilots hired within the past decade would contact me. Within two days, I received correspondence from the air carriers. Three of these companies advised I would receive correspondence directly from the pilot, if she was interested. The fourth company specified three questions only, and only to pilots they selected.

Within 10 days, I received emails from two women flying with the same Canadian air carrier, and two women with two different Canadian air carriers. I also received an email from the company that allowed three questions only, stating I had exceeded their question limit quota and that my questions were being referred to the vice-president of Operations. My three questions were complex and did not ask straightforward questions like: “Why did you become a pilot?” or “Do you have any recommendations for women who want to get a pilot license?”

I received no further correspondence from this company.

All participants who agreed to participate willingly elaborated upon their initial responses in extended email threads. All requested anonymity and have been identified as P1 (Pilot 1), P2, and so on.

P1 is college-educated and works for an air carrier where four per cent of the pilots are female. She feels aviation continues to retain “the stigma of an ‘old boys club.’ ” When she was a teenager, her limited exposure to aviation led her to assume “flying was something someone’s uncle did in their spare time.” She believes young women do not pursue pilot training due to a lack of encouragement in high school, opportunity, or access to a nearby airport. “If young girls could see successful female pilots, maybe it would make the career more accessible . . .”

Exposure to successful women (and men) working in non-traditional jobs and occupations would encourage teenagers to think outside the box. P1 believes the discrepancy between the 12 per cent of female students and the five per cent who seek aviation as a career is partially explained by social conditioning: “There is an amount of societal pressure, even in today’s more progressive society, to be the stay-at-home mom. Where I grew up, even if women did have a career, they are still expected to be the primary caregiver in the family.”

Regarding her experience on the job, P1 occasionally feels like an outsider; this is typically not overt exclusion, but a lack of common interests with the male pilots. She said, “There aren’t often big events that scream sexism; it’s usually the everyday ‘microagressions’ that wear me down. Most men don’t even realize it’s offensive because the things they say have been acceptable in our culture for so long.”

P1 cited several experiences with male pilots and male ramp crew watching to see if she was physically capable of loading large cargo drums — an occurrence that echoed my experience in 1982 when the maintenance engineers stopped working to see if the newbie female pilot could open our company’s massive Second World War-hangar doors. On two separate occasions since 2014, P1 has been mistaken as a flight attendant. Though “the male passenger apologized after the flight, saying he had no ill intent, merely ignorance,” she recalled. “I can’t help but wonder if some people assume that I’m not the pilot, simply because I’m female.”

P2’s first flight at age 10 in a commercial airliner convinced her to pursue a career in aviation — as a flight attendant. Five years later, a chance conversation with a female neighbour convinced her to pursue flight training. To help change the lingering perception, P2 said, “I always try to smile to little girls as they deplane. I have the occasional parent who tells their daughter, ‘Look, girls can fly, too.'”

P2 recalled a negative experience that one of her female colleagues had in 2000 when she began flying for a Northern Canadian air carrier. After this colleague had accumulated sufficient flight time and seniority over a few years, she responded to a posting for a promotion to a larger aircraft. “The manager called her and told her she couldn’t get it because the pilots would refuse to fly with her,” P2 said.

P2 has experienced episodes of sexual harassment and verbal abuse at two different aviation companies, both within the past five years. “This impacted me a lot. Then and now. I was a nervous wreck for months after. I was so afraid of seeing him at work, or worse, being scheduled to fly with them. I am still not over it.”

I understand her reaction. Whenever I was scheduled to fly with one of our senior captains, I was conflicted. Flying with him provided intellectual stimulation and an opportunity to learn from an experienced pilot, but on layovers, I’d refused his subtle advances for months. He never pressured until one night when he sat on the ottoman in front of my chair in the common room, took me by the shoulders, and kissed me. I was speechless. I raced into the bathroom and vomited. After that incident, the harassment and suggestive comments stopped.

P3 believes “a lack of mentors contributes to the small number of female student pilots. . . . I know so many male pilots who grew up with friends of relatives with some tie to aviation.” She began private pilot flight training in the summer of 1992. As the only female student, she felt “conspicuous and invisible.” An instructor who decreed, “Chicks can’t read maps” persuaded her to postpone flight lessons and finish university.

Determined to have a career in aviation, she became a flight instructor. After four years of instructing, she left, “feeling very defeated” by the chief instructor who labelled her a “weak pilot and a weak instructor.” He refused to provide specifics or offer suggestions for improvement, but promoted “a male instructor who had been hired one year later than I . . . to teach on the twin engine . . . despite his questionable teaching record and his determination to date all his female students.” She then got a job flying twin-engine aircraft at a small charter company. She was the only female pilot, but her male colleague pilots treated her with consideration and respect.

When later hired by an air carrier, she initially had the “illusion that any gender discrimination was behind me.” P3 has not been subjected to major sexual or professional misconduct, but her experience echoes that of P1: like most interactions between humans, it’s the little things, the micro-aggressions which reveal so much about humans and our social climate, and which sometimes destroy us.

While attired in full pilot uniform, P3 recalled meeting a mother and her preschool-age daughter on the airport ramp. “The little girl examined me closely and then asked her mom, ‘Is that a cop?’ Her mom replied, ‘That’s the pilot.’ [The toddler] gave her mom a look of disgust and said, ‘That is a girl.'”

I encountered a similar reaction, 30 years earlier, in 1985. Dressed in full uniform, I stood on the ramp of a northern Ontario airport and chatted with an urbane passenger from Toronto.

He said, “It’s great to see your airline has a stewardess for this flight. What are you serving for lunch?”

I decided to use this as an opportunity to educate him about the stripes on my jacket, but he interrupted — “I know what those stripes mean. Surely you’re not the first officer? Really? A female? You’re not going to sit up front, in the cockpit? Didn’t you borrow the coat?”

“I’m one of the two pilots on your flight today,” I responded.

“I’ve never seen a female pilot.”

P4 flies as first officer for a low-cost European airline. At age 29, P4 is the youngest pilot who responded to the questionnaire. She believes “a cultural root” sets the stage for girls and women to see themselves in more traditional careers, a focus that encourages them to “be under-represented in [a] position of authority.”

She added: “From childhood, boys are given toys related to mechanics (cars, trains, planes), whereas girls are given dolls and tea sets. In peoples’ minds, the image of the pilot is still spontaneously associated with a man.”

P5 reported only positive experiences; pilots P6 to P10 inclusive reported mostly positive experiences.

Captain and college-educated P10 said, “There is definitely some inherent sexism towards women pilots. Day-to-day discrimination experienced by me (and many other female pilots) includes sexist remarks . . . from passengers and colleagues. [For example,] women can’t drive so they can’t be trusted to fly airplanes; women are emotional so they cannot handle an emergency situation.”

Some of these comments are intended to be humorous, not malicious, but the impact is identical.

P10 added: “I have to work harder than my male colleagues at times to ‘prove myself.'” However, “I have encountered mostly supportive employers, male colleagues, and passengers.”

Nearly five decades after the first female pilot took the controls of a commercial airliner, some are shocked to learn their pilot is a woman.

Recently retired British Airways Captain Catherine Burton writes, “The most difficult thing about being a woman pilot is overcoming the prejudice that says ‘you can’t do that.’ It’s a deeply ingrained prejudice, often unconscious. . . . I was at a careers fair, in captain’s uniform. Three women came to my table. A year 13 student, her mother, and her grandmother. Gran opened the conversation with, ‘Can you tell us how Tracy [name changed by Captain Burton] can become a British Airways stewardess?'”

Captain Burton learned that Tracy was taking mathematics and physics, ideal STEM subjects for an aspiring pilot, and asked, “‘Why are you asking how Tracy can become a stewardess when she’s so obviously an ideal candidate for pilot training?’ ‘Oh! Can women be pilots?’ asked mum and gran simultaneously. To a British Airways woman captain in full uniform.”

I run a flight school and one of my best pilots/ flight Instructors – man or woman was a woman. I presently have about three woman students which is more then we normally have for our small flight school. How can I attract more female students?

Hi Vern

Thank you for reading and for your interest in attracting more female students. I wish I had the answer!

However, today’s article helps to explain the disconnect between women and a career in aviation and tomorrow’s final in this series offers some suggestions and description of and links to support groups.

Have you asked your three female students what drew them to aviation? I would be interested in their responses. Kindest regards, Lola

Hi there, what’s the name of your school ? I’m starting flight training this coming year and doing my research to find a great school where I would feel at ease learning and not worry about this bs (excuse my language) Thank you.

Would it be possible to send me the articles? I’m having problems printing it/them because of all the other stuff on the screen.

Liz

Hi Liz – Yes! Of course. Thanks for reading. Cheers, Lola

Dear Lola,

This is an excellent article, and you are a superb pioneer.

When one of the women pilots who responded to your questionnaire said, “There aren’t often big events that scream sexism; it’s usually the everyday ‘microagressions’ that wear me down. Most men don’t even realize it’s offensive because the things they say have been acceptable in our culture for so long.”, she was right…. and my thanks to you for not bending, tiring or wavering in your continued crusades for an inclusive and fair society for all.

Yours very truly,

Lise Allin

Great article Lola, you are inspirational! A timely reminder to call people out in their everyday microagressions, so ingrained in our culture that they don’t realise what they are saying/doing. Keep up the good work!

Thank you for reading and for your comments. Big hugs!

Congratulations to all the women’ pilots, continue to encourage women to embrace a career in commercial aviation. Bravoi. Wil

Hi Wil, Thanks so much for reading and for your support.

In the early 90’s I put myself through Civil Engineering Technology studies by driving schoolbus, and (relief) milking cows on the weekend. I drove tri-axle, and worked a construction site during the summer as labour – ecstatic that I was finally being paid for picking up after men. It was hilarious to watch reactions when I hopped in the backhoe, never mind the telescoping zoom-boom to put furniture in the open window of each floor as the dorm rooms progressed. As I moved through my career of part-time teaching and then the exams in the Ontario Building Code, it was always interesting to see the “old boys’ network” at work. I did short-term contracts as an inspector but lost the one I really wanted to a younger man with kids and a church connection to a counsellor on the hiring committee. Through other challenging life events, I came to realize that the best place for me was indeed in the “back row”, quietly running my own design business and helping those who saw my brain first. I’ve developed a long list of evil ways to smack those fools in the forehead with a shovel and tell them to “smarten up!”.

Hi Brenda,

I think you’d be interested in reading Brotopia by Emily Chang. Though Chang specifically discusses the bro culture of Silicon Valley, her observations and findings apply to aviation and all other careers where women are under-represented.

Many thanks for your interest!

Cheers, Lola

Lola ,it was nice to read your article on women in male dominated fields of work. Over the years we have hired several women to work along side the men framing houses and other construction work. what was interesting was comments from homeowners and others watching the work progress. It was noted the younger male employees worked a little harder when the women were doing the same job….i can only reason is they did not want to be outdone by their female workers …also the customers loved to see female employees working in this field …..and why not …they were eveybit as capable as the men.

Lola,

Fabulous article! I thoroughly enjoyed it. I taught ab-initio flying lessons from 1979 – 1981. i had earned my Senior Commercial Pilot Licence with Multi-engine, Class II Instrument, Instructor and Night ratings. My goal was to become a commercial airline pilot. Im 198, personally attended various aviation employers at (then) Toronto International Airport and was told plainly by one of them that “we do not hire women.”

I can honestly say that my employer himself never harassed me in any way and was very fair to all of the staff. My students also were excellent and I never felt harassed by them. My fellow (all-male) instructors however, made the working environment very difficult. I was harassed several times a week. Their tired, never-ending sexist comments were draining and frustrating.

Thankfully, I have a wonderful husband who told me that if it was this bad teaching, it would be much worse if I got into the airlines. He encouraged me to continue my university education, so that I would not have to be subjected to such discrimination again. I completed my Master’s of Law and was fortunate to become an Assistant Crown Attorney. I am very grateful to the women in law who went before me and paved the way. I am very much in awe of the women in aviation who persisted and are paving the way for future female pilots. I include you in there Lola!

Elizabeth Ives-Ruyter

Dear Elizabeth

Thank you so much for reading and especially for sharing your experiences with fellow (male) instructors. Unfortunately, aviation lost a valuable player when your career path veered. Cheers, Lola

Hi Bill Thanks so much for reading the article & for taking the time to comment. And perhaps more importantly for hiring women for construction. SO lovely to hear from you, Lola

I just graduated from college and I am thinking this career. I just had my first demo flight. My instructor is a nice male.

However, reading more articles about sexism in this industry is really discouraging me to invest more in this career.

I had no aviation background and I am not sure can I do better than males. I think maybe I should take an easier career path.

So many thoughts to share! My dad loved to fly and as often as finances would allow while we kids were growing up, he’d rent a Cessna and take it out for a spin, sometimes to Catalina for a “buffalo burger” lunch, or sometimes just for a local flight around our home airport, Santa Ana (where he’d been stationed for training during World War II). When he hit his 50s, he decided to pursue flying more deliberately, and earned instrument and instructor ratings. The pilot who gave him his check rides for these ratings was Tig, a woman, who told him performance was the best she’d seen. His plan was to start a new career as an instructor, but a tragic error by one of his first students resulted in his accidental death. To honor his memory and the time I’d enjoyed flying with him, I completed ground school, soloed, and took my first cross-country — all under the instruction of a female pilot, Luanne Leeson. The day came when I had to confess to my mother that I’d undertaken all of this as a tribute to my dad and somewhat in defiance of her. I was stunned by her response — and the jaw-dropping information she revealed to me: that she, too, had been a pilot! During her service as a WAVE during the war she was a Link trainer, and after the war she decided to follow that love of flying by enrolling in USC’s School of Aeronautics in Santa Maria. There she met and married my dad. Their dream as newlyweds was to work together as FBOs at a small airport. How had I never known of her accomplishments? The next discovery I was to make was in meeting a young guy who had known my dad — and, in fact, had been taking lessons from him before the crash. He cintinued his lessons, though and after he finished his first check ride at SNA, the instructor congratulated him and said, “the only other student I’ve ever tested who performed that well was…” Yep, my dad. My story honors the women pilots who touched my life: my mom, and the amazing instructors Tig and Luanne. Luanne’s signature on my framed clipped wings t-shirt still hangs on my wall, though that first cross country flight satisfied my desire to explore the air. I know she and Tig inspired many women to pursue and master flying — and opened the minds and attutides of many male students about women’s capacity for excellence in the cockpit. Sail on, sailors of the skies!