Estimated reading time 5 minutes, 18 seconds.

The Italian Air Force took delivery of two Lockheed Martin F-35A Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) jets at Amendola Air Base on Dec. 12, 2016, the first such operational aircraft built outside the United States.

That same day, the Israeli Air Force received its first two operational F-35I “Adir” (F-35I) at Nevatim AFB, both of which were assembled in the U.S.

The deliveries marked yet another important milestone for the JSF program as it transitions from developmental to operational aircraft. In August, the U.S. Air Force declared its first squadron of F-35As ready for operations.

While the F-35 program is not expected to conclude system development and demonstration (SDD) flight testing until Oct. 31, 2017–a date the Joint Program Office says will likely need to be extended by a couple of months–for engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney, it has been “pencils down” on the development phase of the F135 engine since mid summer.

“Our development program is over,” Clifford Stone, vice president of international programs and business development at Pratt & Whitney Military Engines, told Skies in a recent interview. “We completed SDD in July.”

Of 38,000 specification points related to the engine, Stone said just seven remain to be resolved, and most of those can only occur once the aircraft reaches enough flying hours. “With some engines, we would say you are mature after 250,000 flight hours; [the F-35] has 50,000 flight hours.”

Just under 300 of the F135 engines, a growth derivative of the F-22 Raptor engine, have been delivered over the past 10 years. But the pace of production is about to ramp up significantly.

Pratt & Whitney is now supplying engines for low rate initial production lot 8 of the program, with lots 9 and 10 under contract and lot 11 still in negotiation. However, the number of aircraft in service is expected to double between now and 2020, bringing the total to around 650 planes, and then double once again over the next two years.

Stone said by 2024, around 1,200 F-35 jets will be in service in 11 countries.

The F-35 fleet has struggled through repeated groundings since testing first began. Issues with the engine’s turbine blades were revealed in 2007 and 2008, and again in 2009 and 2013. Stone said those problems have been resolved and the engine is now meeting a readiness target of around 95 per cent.

“Our spec is to have 90 per cent availability or better in 2020, and we are delivering that now,” he said.

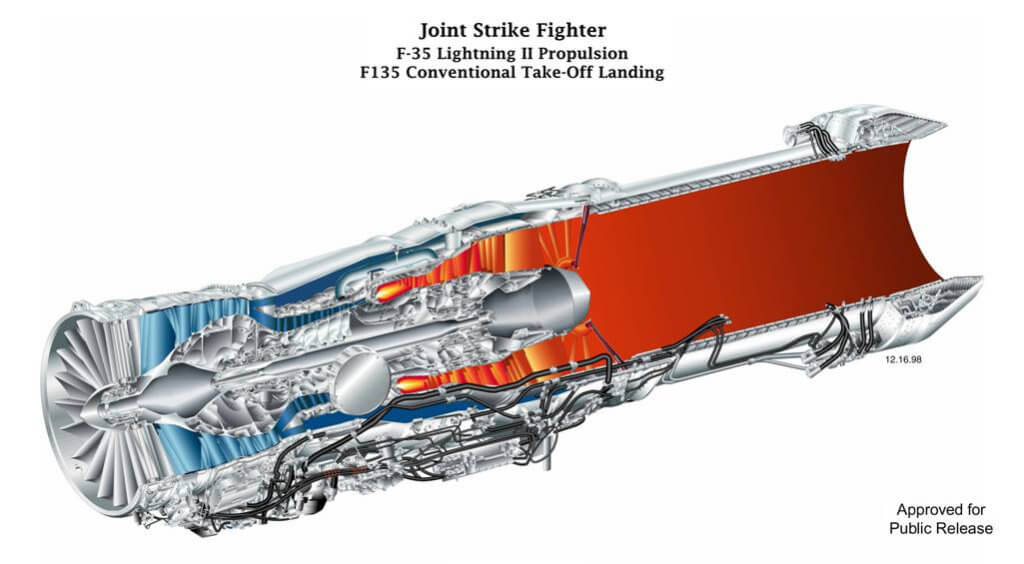

Arguably the most integrated jet engine ever produced, the F135 features redundancies for all critical components and 400 sensors that feed data to two digital engine controllers. In addition to measuring things such as vibration and fuel and oil quality, the F135 boasts capabilities that are probably firsts, Stone said, such as an inlet and exit debris monitoring system and a sensor to assess the health of the airfoils.

“Suffice to say the health monitoring on this engine is robust and advances on where the F-22 engine [left off],” he said, adding that the F135 was designed to withstand and manage foreign object damage. To minimize icing, for example, a heated stripe has been embedded into the guide vane.

While Stone would not disclose the exact cost of an F-35A engine, industry analysts have pegged the price at about $13 million for the conventional takeoff and landing variant (the short takeoff and vertical landing engine is closer to $30 million).

However, Stone said costs have been coming down with each lot and Pratt & Whitney has worked with its suppliers to meet the U.S. Department of Defense’s “Blueprint for Affordability for Production” target of an $85 million fighter jet by 2019.

Among those parts and software suppliers are about a dozen Canadian companies, including Pratt & Whitney Canada, Magellan Aerospace, MDS Aero, and Gastops. The engine program could be worth as much as $2 billion for Canadian industry, he said.

Pencils may be down on the development side of the engine, but work is already underway on future upgrade options. Stone said block upgrades would be made over the life of the aircraft and initial planning is now in progress.

“We are positioning ourselves with either thrust growth capability and/or fuel burn reduction–up to 10 per cent thrust growth, up to seven per cent fuel burn,” he said. “There isn’t a call for that now, but if and when there is, we want to be ready.”