Estimated reading time 13 minutes, 41 seconds.

Tucked away in Fort Erie, Ont., Fleet Canada is an anomaly.

A tour of the Gilmore Road factory–part of which dates back to the company’s founding in 1930–is like stepping back in time. The cavernous 500,000-square-foot plant is staffed by veteran workers sprinkled at a series of workstations, operating vintage tooling by hand, with nary an automated process to be seen.

Save for a much smaller present-day workforce, you can almost close your eyes and imagine how the Fleet Aircraft factory looked during the Second World War, when almost 4,000 people–mostly “Rosie the Riveters”–cranked out single-engine Fleet Fawns, Finches and Forts for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Fleet also made Cornells for Fairchild and supported Victory Aircraft in Malton, Ont., which made the Avro Lancaster bomber. At the height of its wartime production, Fleet was turning out about 160 complete aircraft per month.

While the hustle and bustle of the war years is long past, Fleet Canada–as it is now called following an employee buyout in 2006 from then-owner Magellan Aerospace–remains committed to craftsmanship and old world quality.

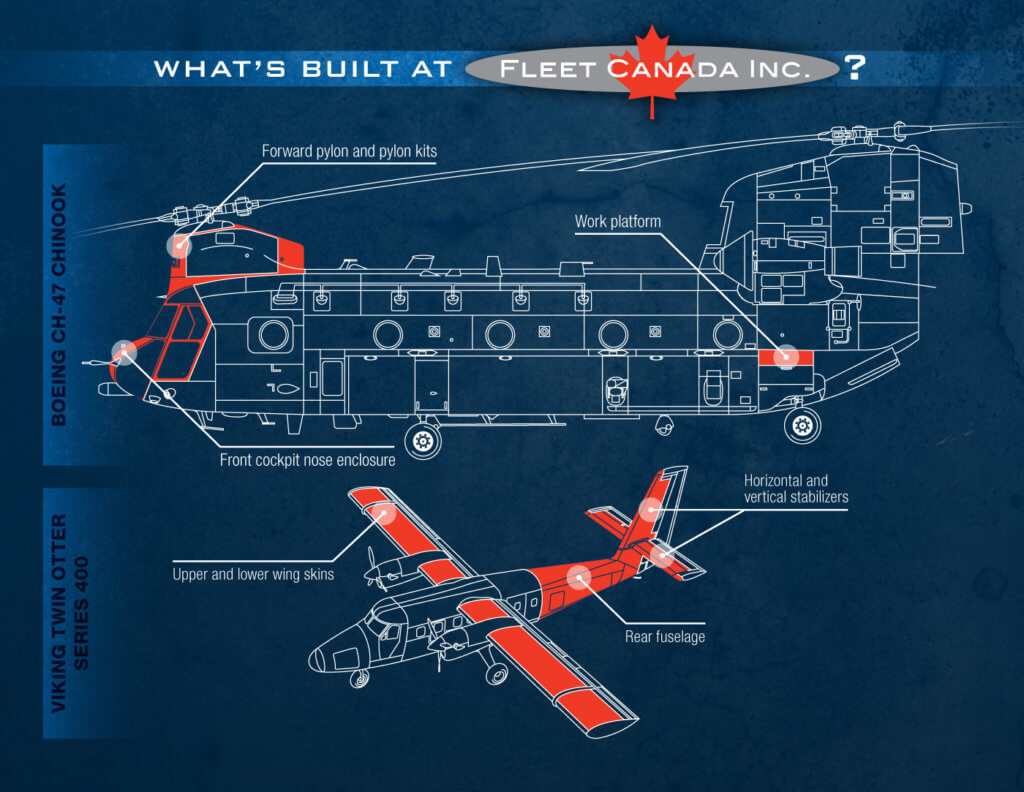

Today, the build-to-print aerospace manufacturer makes the bonded wingskins for Viking’s Series 400 Twin Otter–as it did for every legacy Twin Otter ever made by de Havilland Canada–as well as the plane’s rear fuselage, fin and horizontal stabilizer, and interior bonded panels.

Fleet’s other big contract is with Boeing. The Fort Erie company makes the front cockpit nose enclosure for the CH-47 Chinook heavy-lift helicopter, from metal-to-metal and composite bonding stages to final assembly and paint. On average, Fleet completes four to five Chinook cockpits per month.

While revenues from the Twin Otter and Chinook business pillars are relatively equal, the remaining 30 per cent of Fleet Canada’s $20 million business book is made up of some work on the Boeing KC-46A tanker, spares production for Bombardier’s Q300, Challenger, CRJ, Lear, and Dash 7, and detail work for Erickson Aircrane.

Winds of change

While it stays true to its history of handcrafted excellence, Fleet Canada is every inch an organization in transition. Like a modern-day butterfly emerging from the cocoon of yesteryear, the manufacturer is undergoing a slow and steady metamorphosis.

The seeds for change were planted in 2003 when company president and CEO, Glenn Stansfield, partnered with 14 minority employee shareholders to buy the business from Magellan Aerospace (previously known as Fleet Aerospace).

It took three years, but the deal was eventually concluded in February 2006.

“It’s a real Canadian success story,” Stansfield told Skies in the company’s boardroom. “We started our business 10 years ago with 90 per cent Bombardier work on the Q300. Ninety per cent of the exterior surface of the Q300 was bonded here in Fort Erie. Slowly, we started to evolve into other customers.”

When Viking Air decided to launch its Series 400 Twin Otter in 2007, the OEM approached Fleet Canada, which had been the only company to ever make the wingskins on the legacy aircraft. “Before you knew it, we were doing the rear fuselage, the fin, the horizontal stabilizer, and putting the things together, and all the bonded panels inside the aircraft,” said Stansfield. “We were building 35 or 40 per cent of the total structure of the Twin Otter. Viking is a cornerstone program for us.”

Stansfield is passionate about the work that is done at Fleet Canada. His ties with the company go back to 1974, when he was hired as a production electrician on the Boeing 707 program at the age of 20. It was his first full-time job.

After working at Fleet Aerospace (as it was then called) for 18 years, Stansfield left to start an aerospace fastener business. Years later, he found himself working for the Niagara Enterprise Agency, which had ties to a community venture capital fund. One day, he got a call from a former colleague who told him Magellan was looking to pull out of Fort Erie.

Stansfield knew the workforce and the quality products they made. If he could help to bring all the pieces together, he was confident the deal could be done.

“The Town of Fort Erie helped us do a viability assessment. All indicators said if you could have a situation without dissidence, with product priced and structured in the right way, it would be a success.”

In the end, everything fell into place. “Magellan was supportive, offered start-up assistance and a long-term lease on the facility; Bombardier was patient and wanted to offer us the opportunity to keep the Q300 work here; and we had venture capital investment,” said Stansfield.

Fleet Canada was re-born as a privately held company with just 35 employees. But by the end of the year, the staff roster had increased to just shy of 100.

“You couldn’t have had a better start to a new company–an experienced workforce; a very supportive landlord in Magellan; and a customer, Bombardier, for 25-plus years. We knew the product,” recounted Stansfield. “We shipped our first product within about 12 days of closing the deal. We came flying out of the chute.”

Within two years, Fleet Canada had repaid all its loans and beat financial projections. Around the same time, its workforce voted to decertify the union, even though a five-year collective agreement negotiated in 2006 was still valid.

The Boeing way

In September 2013, Fleet Canada, with assistance from Magellan, landed a major contract with Boeing to build the front cockpit nose enclosure for the Chinook helicopter. The contract was the catalyst that would change the company’s future direction.

It also proved to be an opportune time to bring in a new investor to solidify the company’s foundation. Mark Maybank, former chief operating officer of Canaccord Genuity Corp., joined Stansfield at the helm of Fleet Canada. The partners set out to improve corporate governance and enhance strategic planning.

In 2014, the Canadian government revamped its longstanding Industrial and Regional Benefits (IRB) program, which had been in place since 1986. The changes were made following the 2011 Jenkins report on innovation. Among the new requirements, foreign contractors (or “primes”) must now present their so-called “value proposition” when bidding on a Canadian government contract.

Points are awarded to bidders based on a weighted-and-rated system that says they must be very specific about which technology benefits they will bring to Canada. Primes must now identify, in advance, a mix of Canadian small and medium businesses (SMBs) and other contractors with whom they plan to work.

In the meantime, companies that want to be considered for the Industrial and Technological Benefits (ITB) program, as it is now called, can register for free in a database that quickly links their capabilities with those being sought by a prime contractor.

With 160 employees, Fleet Canada fits squarely into the SMB category. Not only that, but the company boasts a suite of attractive capabilities that are in demand by prime contractors searching for skilled Canadian partner companies. Fleet holds several key certifications from Nadcap, the established aerospace global accreditation program, including chemical processing, composites, heat treat and non-destructive testing.

Certifications are important, but so is process. The Chinook contract also prompted some changes on the shop floor.

“Boeing wants you to do things the Boeing way,” noted Marika Kozachenko, Fleet Canada’s business development manager. “Within reason, we had to find a way to up our game and strengthen our processes. We are focused on making things repeatable to ensure we are performing the right process the same way, every time.”

Calculated transformation

In 2015, the company’s leadership team launched a two-year, carefully executed plan to modernize the operation on three fronts.

First came the adoption of lean manufacturing processes, pioneered by Toyota after the Second World War and migrated to the aerospace industry in more recent years.

Second, Fleet Canada moved to implement a modern enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, scheduled to go live at the end of 2016, which will represent a quantum leap forward in the company’s ability to modernize and document its processes and procedures and track data in real time.

The third priority is workforce rejuvenation–five years ago, the average age of the workforce was 57; today, it’s down to 50. Sixteen people have been hired by Fleet in the past year and a half, facilitating the transfer of knowledge between older workers and their younger colleagues.

One of those hires is Jean-Sébastien Coulaud, an aerospace engineer from France with past experience as an automotive manufacturing manager at Renault, as well as time spent at Airbus. He joined the team a year ago as general manager.

“Succession has been a huge focus in our business for the last four years,” said Stansfield, who added that Coulaud will be ready to take the baton from him in about three years. “Our workforce succession program is moving ahead. You don’t replace a 40-year craftsman in the shop with someone off the street. But Niagara is rich in talent, and we are partnering experienced employees with new people.”

Coulaud is leading the team that is driving change at Fleet, applying lessons learned from the automotive world to the highly specialized aerospace industry.

“We are bringing in some of the best practices from lean manufacturing and job standardization,” he told Skies. “We’re moving to an exact method of manufacturing using specific tools, and there is no way around it. It is the spec, and we’re limiting variability in the way we build, because that improves the quality of our build.”

Great improvements have been made in the last year. Today, all work packages are completed on time and the company has gone from a red to a silver rating in the Boeing quality system. Now, it’s going for gold.

“These are some of the metrics we are trying to make sure we meet. They will allow us to land more work in the future,” explained Coulaud.

When considering future work packages, he said it’s important to note that Fleet Canada is not “opportunity constrained.” There is lots of potential work out there, but the company is limited by its current capacity.

Once all processes have been streamlined, it will be time to pursue a few other contracts. The ideal arrangement will fit into Fleet’s core competency: lower-rate, higher-margin jobs that don’t interest bigger, highly automated companies.

“In five to six years we want to double revenues to $40 million while maintaining a healthy profit margin,” said Coulaud. “We have two major business pillars now [Chinook and Twin Otter] but we want to have three to five all together, to diversify the business.”

Stansfield has his sights set on Bombardier’s C Series program, for example.

“We’ve quoted some work on the C Series through a third-party customer. We’d love to get a foothold in that program,” he said. “We think that is a very good long-term business silo.

“We’re also watching intently to see the government’s decision on the new fighter. The opportunity to bring in more new Boeing business is exciting [if Canada places an order for the Super Hornet]. They’ll be looking for qualified outlets to put work into Canada. We think we’re in a very good spot.”

Viking’s recent acquisition of the type certificate for Bombardier’s CL-415 waterbomber may also translate into interesting future possibilities. As well, Coulaud said Airbus represents another avenue for possible diversification.

In the meantime, Fleet Canada’s management team will concentrate on getting as much as possible from existing work packages, especially Boeing’s CH-47 helicopter program. Sometimes that means working for a competitor–such as the parts Fleet makes for B.C.-based Avcorp, which are used to help fulfil that company’s Chinook contract.

Stansfield said while current projections call for Fleet Canada to double its revenues over the next few years, it will take care to stay below the 250 full-time employee cap that officially defines an SMB in Canada for ITB purposes.

No widgets here

Brian Havill is an assembly fitter on the Twin Otter program at Fleet. He’s been there for four years, but did a previous stint at the company 14 years ago. He said times have really changed.

“I think it’s better now. There is no union, so you can do different things and there is more versatility,” said Havill, who completes the final assembly of the Twin Otter’s rear fuselage.

“I like that they’re getting structured and implementing the 5S [workplace organization] program and cleaning everything up,” said Havill. “That’s what you need to be successful; it’s going in the right direction.”

He is proud of the work done at Fleet. “You’re building something people fly–it has history to it.”

That sense of pride is most evident on Wednesdays. That’s when Stansfield kicks off the workday with a company-wide meeting that delivers a simple message: “We don’t make widgets. We make parts for aircraft that save lives.”

At one such meeting, Stansfield showed photos of a Royal Canadian Air Force CH-147F Chinook participating in its first domestic humanitarian mission during the devastating wildfires in Fort McMurray, Alta.

On the Wednesday that Skies visited, the team discussed the dramatic developments at the South Pole in late June, when a Twin Otter operated by Calgary’s Kenn Borek Air braved total darkness and incomprehensible cold to successfully complete a medical evacuation mission.

“I told them, ‘How proud are you to have made those wings? Those are Canadian heroes, those pilots who went down there and did that. No other plane could have done it, and no other country has pilots who could do it. We have some great stuff going on here!'”

While a lot is changing at Fleet Canada, pride in a job well done has always permeated the old factory on Gilmore Road, ever since it was founded almost 90 years ago. Today, having just celebrated its tenth anniversary since restructuring, the company is gearing up for what promises to be a bright future.

As Kozachenko said, “It’s a wonderful thing to see a company rowing in the same direction.”

Lisa Gordon is editor-in-chief of Skies magazine. Prior to joining MHM Publishing in 2011 to launch Skies, Lisa worked in association publishing for 10 years, where she was responsible for overseeing the production of custom-crafted trade magazines for a variety of industries. Lisa is a graduate of the Journalism program at Ryerson University.