Estimated reading time 17 minutes, 53 seconds.

The combined area of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Nunavik (the northern third of Quebec) is approximately 3.8 million square kilometres (1.5 million square miles), or about 38 per cent of Canada’s total area. Given the great distances between communities and the lack of surface transportation infrastructure, air is the primary transport mode used to support the combined remote population of roughly 100,000.

The largest aviation service provider across Canada’s Far North is Bradley Air Services Limited of Ottawa. Operating as Canadian North, it connects 25 northern communities with the major cities of Edmonton, Ottawa, and Montreal. Having been around for nearly eight decades, it’s no surprise that the company has evolved significantly since it first took flight.

Start Small, Then Build

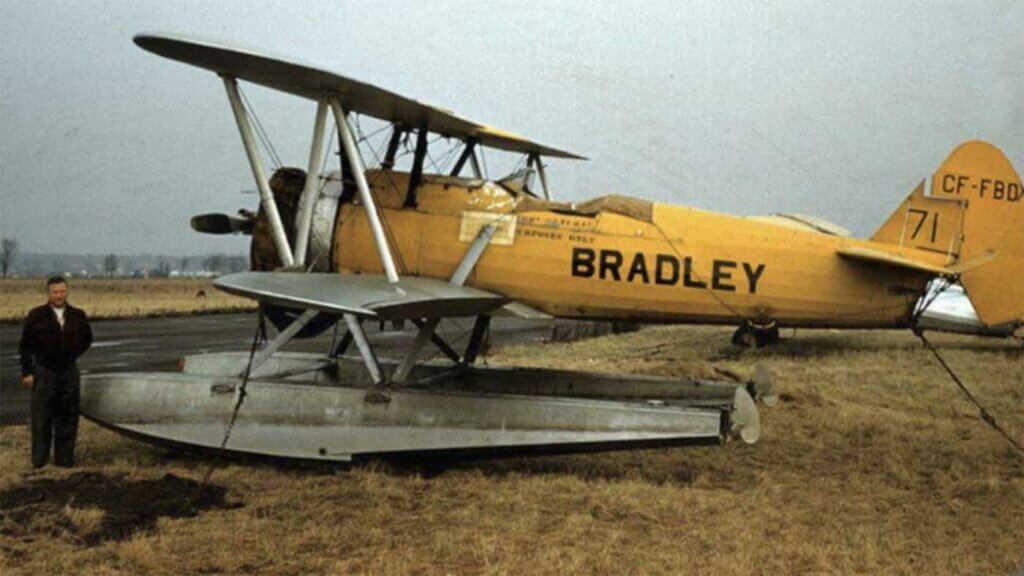

In 1946, aviation pioneer Russell Bradley created Bradley Flying School at Ottawa’s Uplands Airport with a single Piper Super Cub. It later became Bradley Air Services and moved to nearby Carp, Ont., subsequently taking up charter work in an effort to diversify its revenues. During the ‘50s, Bradley supported the development of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line of northern radar stations with four Cessna 180s; used five Stearman biplanes to spray budworms in New Brunswick; and enabled the geological survey of Canada’s High Arctic activities with numerous Super Cubs.

By 1960, Bradley Air had become a Piper dealership and was operating a diverse fleet of single- and twin-engine models. Two interesting types were the Lockheed P-38L Lightning (CF-NMW) that flew photography missions, and the large Sikorsky S-55 helicopter (CF-KQD) that performed electromagnetic surveys.

The ‘70s brought new opportunities, especially across Canada’s Far North where petroleum, mining, and scientific exploration boomed throughout the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Bases were established at Resolute Bay, Eureka, and Iqaluit in Nunavut, and the fleet welcomed numerous DC-3s and Twin Otters — some of which flew for the U.S. Air Force in Greenland and the U.S. Navy in Antarctica.

Bradley Air’s initial scheduled services began in 1973 when Twin Otters connected Ottawa with North Bay and Sudbury, Ont. “First Air” was the brand used for this operation, and it would eventually become the company’s trade name.

In 1978, the company purchased the Baffin Island operations of Survair, giving it a scheduled network in the eastern Arctic. The company entered the jet age in June 1986, when it acquired a Boeing 727-90C. “C-FRST” provided the required capacity and speed to efficiently move passengers and cargo between Iqaluit and Ottawa.

Over the following 30 years, the route network and the fleet expanded with the acquisitions of Ptarmigan Airways in 1995 and Northwest Territorial Airways in 1997. First Air’s Boeing 727 fleet was later replaced with different 737 variants, and its Hawker Siddeley HS-748 turboprops were supplanted by ATR 42s and ATR 72s.

The company’s freighter business also grew; two Lockheed Hercules were used between 2006 and 2015, and a Boeing 767-223F was operated from 2009 until 2014.

Northern Competition

Meanwhile, another carrier had become a significant competitor. Canadian North launched on Oct. 29, 1989, with nine 737-200Cs serving 10 communities in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut from bases at Edmonton and Montreal. The division of financially challenged Canadian Airlines International was sold to two Indigenous investment companies in September 1998.

A decade later, First Air was flying to 17 of the 21 communities served by Canadian North. The duopoly was resulting in excess capacity and a less than optimal utilization of assets. As time passed, it became apparent that the financial sustainability of Canada’s northern air transportation system was at risk.

Merger talks between the owners of First Air and Canadian North — Makivvik Corporation of Kuujjuaq, Que., and Inuvialuit Regional Corporation of Inuvik, N.W.T., respectively — began in April 2014. Then, on July 6, 2018, the two carriers announced their intention to merge. Federal government approval was granted just over a year later, and the carriers began operating as one in November 2019 under the Canadian North banner, utilizing the First Air livery.

Today, Canadian North dominates the domestic market north of the 60th parallel. The airline provides scheduled passenger services, hauls cargo, and flies ad hoc passenger charters for customers including natural resource companies, tour operators, and sports teams.

The Network

Upon first glance, the dots on Canadian North’s route map resemble a shotgun pattern. A more detailed examination of the carrier’s schedule reveals a network based on two hubs: Yellowknife, N.W.T., in the west, and Iqaluit in the east. Yellowknife is connected with four N.W.T. destinations, seven Nunavut communities, and Edmonton in the south. Iqaluit is connected with 12 destinations in Nunavut, one in Nunavik, as well as Ottawa and Montreal.

Service to Grise Fiord (Canada’s most northerly community) is provided from Resolute Bay by Kenn Borek Air. Additionally, Calm Air International feeds traffic into the Canadian North network at Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, from Winnipeg, Man.

The Fleet

Canadian North’s 32 aircraft are based on two reliable families – Boeing 737 jets and ATR turboprops. Within each of those are a variety of models that are ideal for the different missions flown.

The 17 737s include nine -300s, four -400s, and four -700s. There are seven 737-300 passenger aircraft fitted with 136 seats, as well as two Combis that can be configured with either 136 seats, 80 seats with three pallets, or as a full freighter. The four 737-400s include a dedicated passenger model with 156 seats, two Combis each configured with 72 seats and slots for four pallets, and one dedicated freighter that can carry up to 48,000 pounds in 11 pallets. Finally, the four 737-700s each accommodate 134 passengers.

With the retirement of its last 737-200C (C-GDPA) in May 2023, the company no longer has any gravel-kit equipped jets. Unprepared surface work is now the responsibility of its 15 turboprops.

Canadian North has seven ATR 42-300s, six ATR 42-500s, and two ATR 72-500s. Six of the 42-300s are Combis that can be configured to carry either 42 passengers, 10 passengers with cargo, or only cargo, while one 42-300 is a dedicated freighter. The six 42-500s each have 42 seats, and the two 72-500s are dedicated freighters.

The Team

Canadian North has approximately 1,350 full-time equivalent employees, including some 240 pilots, about 160 aircraft maintenance engineers (AMEs), and approximately 190 flight attendants. There are around 265 airport workers, including check-in staff, ramp workers, and flight kitchen personnel. Impressively, 617 employees have been with the company and its predecessors for more than a decade.

Support Capabilities

In addition to offering scheduled passenger services, cargo operations, and charter work, Canadian North has other capabilities in the areas of maintenance, engineering, and training. Its maintenance facilities are located in Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, Yellowknife, and Iqaluit. The Ottawa and Yellowknife hangars, in particular, are dedicated to heavy maintenance work on the airline’s 737s and ATR turboprops.

Engineering is another vital pillar of Canadian North’s support capabilities. The company is a Transport Canada approved Airworthiness Engineering Organization, and has the ability to provide structures, avionics, and mechanical systems work.

The airline also places a strong emphasis on training. Canadian North has a Learning & Development Centre in Ottawa, complemented by secondary learning facilities in Iqaluit and Yellowknife. Across these facilities, more than 200 courses, including Transport Canada approved certificate programs and Safety Management System courses, are provided.

Moreover, the airline also performs advanced pilot training and type endorsements on various aircraft types, as well as basic and recurrent maintenance and aircrew schooling. Its Edmonton facility houses the airline’s own Level D 737-300 full flight simulator.

S.W.O.T. Analysis

To gain a better understanding of any business model, and therefore appreciate how a company may perform in the future, it is helpful to review its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, otherwise referred to as S.W.O.T.

Strengths

• Dominant Mode. In the Far North, air transportation has little competition from surface transportation modes, making the airline the dominant mode of transport.

• Strong Corporate Culture. By practicing respect, recognizing integrity, and providing service excellence, the company is able to attract and retain talent.

• Community Investment Program. Canadian North assists its customer base by providing passenger air travel and cargo service to not-for-profit organizations related to Indigenous education, sports, and culture.

Weaknesses

• Northern Climate. Harsh weather that is typical in the Far North often results in scheduling challenges and higher than industry normal operating costs. If anything, these factors should continue to dissuade potential competitors.

• Geographic Consequences. Given the distance of its operations from the southern sources of aircraft components, meaningful investments must be made in parts inventories in order to remain efficient.

Opportunities

• Cargo Growth. Having four dedicated freighters, including a 737-400, two ATR 72s, and an ATR 42, the carrier is prepared for an increase in cargo traffic. This past August, Canadian North unveiled its plan to double the size of its cargo facility in Ottawa. The airline and the Canadian government will each contribute $11 million to the complex that is due to be operational by 2026. The expansion is in response to an increased level of online shopping, the need for expedited grocery deliveries, and the demand for stable food supplies in the event of prolonged adverse weather.

• Tourism. The vast wilderness of Canada’s Far North offers extraordinary experiences for tourists seeking to make long-time dreams come true. The pandemic put a hold on such activity for a number of years, but demand remains from travellers around the globe. Related services, such as accommodations, dining, equipment rentals, and adventure tours, would enhance the local economy.

Threats

• Economic Weakness. Employment and Social Development Canada has forecast that the Northwest Territories’ GDP will contract slightly (-0.4 per cent) in 2023, then rebound by 0.8 per cent in 2024. Its outlook for Nunavut is more optimistic, with a 7.4 per cent increase in 2023, followed by a 12.3 per cent improvement in 2024. The Northwest Territories’ “Economic Review 2023-2024” confirms that northern economies are currently challenged by interest rates, the weak Canadian dollar, and a lack of workers.

• Personnel Shortage. As more “baby boomers” retire, it has become apparent that the aviation industry requires more talent. The current shortage of pilots and AMEs is a concern that has been recognized by management. As such, Canadian North has created an Inuit pilot training program with Providence University College of Otterburne, Man. High-potential Inuit students will be selected for training, and those who are successful in their studies and meet the regulatory requirement will be offered employment.

The Future

In mid-October this year, Canadian North announced an unexpected leadership transition. Michael Rodyniuk, who served as the airline’s president and CEO from July 2022, stepped down, and VP of sales, marketing, and distribution, Shelly De Caria, assumed the role of interim president and CEO.

De Caria is the first Inuk to lead Canadian North, and is continuing to lead her VP portfolio alongside her new appointment.

“Further details regarding the leadership transition, including the process and timeline for selecting a new CEO, will be shared as they become available,” the airline said in an Oct. 16 press release.

Before he departed Canadian North, Skies asked Rodyniuk where he saw the company in 10 years. He replied: “Canadian North is poised for a successful decade ahead.

“With the easing of previous merger conditions this April, we’re now accelerating our path to recovery,” he continued. “Our shareholders are backing a fleet renewal featuring state-of-the-art Boeing 737NG aircraft, which will elevate the customer experience. Investments in infrastructure and automation are streamlining our operations and equipping our team for success, while cutting costs. Our unwavering commitment to safety and the well-being of Inuit communities across Canada’s Arctic remains at the core of our mission — to make life better in the communities we serve.”

The company’s goal is to remain financially viable while providing safe and reliable air transportation and employment opportunities for the citizens of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut — its ultimate owners. The airline adheres to the three tenets of safety, community involvement, and profitability, which has served Canadian North well for many decades — and should allow it to continue for many more.