Estimated reading time 21 minutes, 57 seconds.

Bill McBride says his involvement with the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum (CWHM) gave him the chance to shine.

McBride, 81, is member number 35 in the Hamilton, Ontario-based organization, which was founded in 1972 and is now celebrating a half-century of protecting and preserving Canada’s wartime aviation history.

He has worn many hats since the early days of the organization, when it was just a handful of guys and a Fairey Firefly housed in Hangar 3 at the Hamilton Airport.

“Mostly, we felt we didn’t have a clue what we were doing,” laughed McBride in a recent interview with Skies. “When I first saw the Firefly, it was behind a tarp. There was a toolbox beside it with metric tools and boxes of spare parts. That was it. That was the beginning of the museum.”

That Firefly was purchased by two men with a dream. Pilots Alan Ness and Dennis Bradley had originally hoped to buy a P-51 Mustang, but when they realized the price tag was beyond their means, they set their sights on a Firefly for sale in Georgia. When they traveled down to see it in 1971, they weren’t impressed. The aircraft was dirty and had been parked in a field for two years. But when it started right up, so did Ness and Bradley’s vision.

They put $5,000 down and paid another $5,000 when the Firefly was delivered to Toronto in October 1971. Over that winter, the pair teamed up with fellow Torontonians Peter Matthews and John Weir, who provided crucial financial support, to restore the aircraft.

On June 4, 1972, the low-wing cantilever monoplane took to the skies in its first post-restoration flight. The group named itself Canadian Warplane Heritage (the “museum” moniker came later) and by October of 1972, it had moved to the Hamilton Civic Airport (now John C. Munro Hamilton International Airport), located in the small community of Mount Hope.

That’s when McBride got involved.

“The first thing I ever did to participate was wash the airplane.”

He described the excitement of the early days, when more and more people began hanging around the airport, buying into the vision of restoring vintage warbirds to flying condition. In those days, Hamilton Airport was home to three busy flight schools. It was a magnet for Second World War veterans, who were drawn to the idea of joining a club dedicated to preserving wartime aircraft.

“It was very exciting. We were doing a lot of flying,” said McBride, who learned to fly at Hamilton Airport in 1958 and got his commercial licence in 1967. “A lot of aircraft involved with the museum were privately owned. It was a very exciting time.

“Finally, the idea clicked into someone’s mind that if we were going to help out, why don’t we have some kind of a membership?” he recalled.

Bradley tasked McBride with creating a membership certificate for all 55 original members, about half of whom were local residents. The remainder were members of the U.S. warbird community who supported the fledgling organization.

In March 1973, it was officially registered as a charitable foundation, taking on the name “Canadian Warplane Heritage Foundation.” This allowed it to accept donations of aircraft, artifacts, and funding to enable its mission of restoring and flying historic aircraft.

Beyond the Firefly, the next two aircraft were donated by co-founder Weir: a de Havilland Canada Chipmunk (CF-POW), and a de Havilland Tiger Moth (CF-EGZ). Next in line was Harvard CF-UUU, or “Triple U,” which heralded the beginning of the CWH Harvard Demonstration Team in the spring of 1973 — a team that continued to perform until 1978.

Over the years, the collection continued to grow with many exciting acquisitions, including the Avro Lancaster bomber, which was delivered in November 1979.

Today, there are 48 aircraft in the CWHM collection, and the museum boasts nearly 4,000 members — 300 of whom are active volunteers.

But, while passion has always fueled their cause, there have been many bumps in the road over the last half-century.

Sadly, co-founder Ness was killed while performing in the Firefly at the 1977 Canadian International Air Show in Toronto. With Ness gone and its flagship Firefly destroyed, the group thought about ceasing flight operations.

But in the end, they stuck to the original vision of operating a flying collection — something they agreed Ness would have wanted.

It was the museum’s first major setback, but not its last.

On Feb. 15, 1993, disaster struck when the north side of Hangar 3 was completely engulfed by fire. A total of 55 firefighters battled the blaze at its height, which destroyed five cherished CWHM aircraft: a Hurricane, an Avenger, an Auster, a Stinson, and a Spitfire. Priceless maintenance and office records were also lost.

Mercifully, the Lancaster was parked on the south side of the hangar, separated from the north side by a brick wall. That wall, plus the heroic efforts of the firefighters, saved the museum’s prized Lancaster from certain destruction.

Spirits were low, but museum members rallied behind CWHM general manager, Jack Evans. Standing in front of the smouldering wreckage, he pledged during a television interview that the museum would rise from the ashes to become even better.

Thanks to the perseverance and dedication of its members, that’s exactly what happened.

Pulling Together

Dave Rohrer is the current president and CEO of the CWHM. He’s been involved for 22 years, starting off as the organization’s volunteer chief pilot in 2000.

“One of the things that strikes me about our history is that it hasn’t all been smooth or easy,” he told Skies. “The museum has gone through difficult and challenging times. The thing that comes through every time is our ability to come together, work as a team, and adjust to the situation.”

He cited Ness’s death and the 1993 hangar fire, but also mentioned the challenges involved in moving to the museum’s current building in 1996.

“We were $2 million in debt and spent the early 2000s in financial distress, where we didn’t know if we’d make payroll,” said Rohrer. “Then, there was the downturn of 2008 and always the high cost of maintaining the airplanes. Through it all, the staff, members, and volunteers have pulled together to overcome. That’s what impresses me most about this museum, and I think that bodes well for the challenges of the next 50 years.”

He said the character of the museum is unique, and there’s none other quite like it. While a flying collection of aircraft is key to that one-of-a-kind recipe, Rohrer admitted that, too, may change in the future.

“A lot of the aircraft we fly today may not be flying in another 50 years,” he pointed out. “But that doesn’t mean we won’t continue to be a flying museum. As long as we can safely maintain and operate the aircraft, we will. And there will be other, newer aircraft to fly in the future.”

But age is not the only threat to the airworthiness of the CWHM’s current fleet of aircraft. As concerns about environmental impacts continue to grow, the race is on to develop an acceptable alternative to 100 octane Low Lead (100LL), or avgas. Avgas powers piston-engine aircraft, including the entire CWHM fleet, and it is the only leaded fuel that is still mass-produced. Various efforts are underway to develop a lead-free alternative, but it may still be years before one is readily available.

Rohrer and the team have spent many an hour considering the future.

“I started thinking, how can we enhance our financial viability if we can’t fly in the future?” he said. “The challenge is to become more interactive and create more immersive digital customer experiences that will reach younger Canadians.”

With most Second World War veterans now gone, Rohrer and the museum staff talked about how to bring their stories to life for young and new Canadians.

“We have many new Canadians through immigration and many young Canadians who have no family attachment to what these aircraft represent. We must create that bond with them; tell that story.”

Creating a Digital Experience

Working with a company called Parallel World Labs, which created Norway’s Rockheim digital music museum, Rohrer and his team investigated some options to create their own immersive digital experience. But at $1.67 million, the price tag was too steep.

Enter philanthropists Michael and Carol Desnoyers of Ancaster, who contacted Rohrer out of the blue in 2021.

“He and his wife wanted to come tour the museum and hear about our needs.”

The couple committed $400,000 to retain the services of Parallel World Labs. Meanwhile, the museum applied for and won a Heritage Canada grant of $548,000, the maximum amount possible. And, once the grant was confirmed in August 2022, the Desnoyers increased their commitment to $1 million.

“Now, we have $1.548 out of the needed $1.67 million, so we’re going,” said Rohrer.

The new four-phase project, targeted for completion in 2024, will make good use of the museum’s treasure trove of old film, including veteran interviews.

The first phase will be the creation of an immersive dome. It will contain six large circular screens, or portals, that will tell the stories of individual Canadians using digital projection technology.

“In a commercial sense, those screens can be adapted to promote any message for any group renting the museum,” pointed out Rohrer, who added that any revenue source is important to the museum, which does not receive regular government funding.

“For the second phase, we’ve identified six veterans and we’re building a story around them,” he continued. “We’ll take those people and use our old film, which is being digitized, and we’ll create metahumans (avatars). When you walk in, you’ll see a portrait of them and what their life represents. But then you will see them standing there and literally be able to converse with them.”

Phase three of the ambitious project will include a high-definition interactive cinema that will bring the museum’s historic film collection to life. Viewers will be able to click on a topic to watch a 90-second clip.

And finally, the fourth phase will include an augmented reality experience that will see users “scan” the aircraft in the hangar with their smartphones to see inside cockpits, cabins, and inner workings.

Sharing the Stories

The Firefly and the Harvard were the aircraft that attracted the attention of a young Al Mickeloff, who used to go plane spotting at Hamilton Airport with his grandfather, a former Bristol Bolingbroke pilot. Today, Mickeloff is the museum’s marketing manager, but he remembers those early days well.

“You’re a sponge for information at that age, so I went out and learned about the aircraft and joined as a member in my late teens,” he recalled. “One of my first volunteer jobs was in the back of the Lancaster, scooping bird poop out from in between the floor joists.”

He vividly remembers the Lancaster’s first post-restoration flight on Sept. 11, 1988.

When asked to name the top three “jewels” in the museum’s collection, Mickeloff paused for a moment.

“First is definitely the Lancaster, one of only two flying in the world. Second, I’d say, is Douglas Dakota FZ692, the only aircraft in our collection that saw combat duty, including flying on D-Day. Third would be our Firefly (a replacement acquired in 1979), because it’s the flagship of the museum — the first aircraft type in our collection, the one in our logo, and the one that got me into aviation.”

While the Dakota is the only aircraft that saw combat, there are many others that have incredible stories. But what makes the CWHM so special to so many people is the emotional connection it sparks to their own experiences — whether on the hangar floor, on the ramp, or soaring through the skies.

In 1974, founder Bradley asked member number 35, McBride, to be the founding chairman of the first Hamilton International Airshow, a position he held for three years.

“Of all the things I did that I remember, that was the one that took me out of the obscurity of working in the appliance division of Westinghouse,” recalled McBride. “I always say the airshow is what put me in a position to shine.”

Since that opportunity, McBride has volunteered to help with just about every task at the museum, from applying roundels on airplanes to hosting VIP tours to MCing major events.

More recently, McBride said he was honored to receive the first Dennis J. Bradley Memorial Award at the museum’s Fifty Years Gala on Oct. 15, 2022. Other celebratory events were held this year, including a reunion and the SkyFest 50 aircraft showcase in June.

McBride shares the belief that a positive attitude and teamwork are the secrets to the museum’s success. As someone who knew both Bradley and Ness from the beginning, McBride thinks they’d be pleased with how far the museum has come.

“In his wildest dreams, Dennis didn’t expect it would become this big operation with so many members — it really is a leader in the world aviation museum scene.

“As for Alan, I think he never would have envisioned this, but at the same time, I think he would have welcomed it,” continued McBride. “I think he had the kind of vision to see it becoming something very grand.”

Indeed, the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum is so much more than a collection of inanimate aircraft. The magic happens when those aircraft meet the passionate hearts and talented hands of the volunteers and staff who keep the doors open — in good times and in bad. There’s simply nowhere else they’d rather be.

“I get a lot of credit about how much I’ve given this place,” concluded McBride. “But it’s given it back to me in spades. The CWHM doesn’t owe me a thing. I’ve met royalty, regular folks, flown all over the place, and I have about 500 hours of flying CWHM airplanes. It brought talents out in me that I didn’t know I had. This is what keeps me out of the mall, and out of the pool hall when I was young. We have enormous fun.”

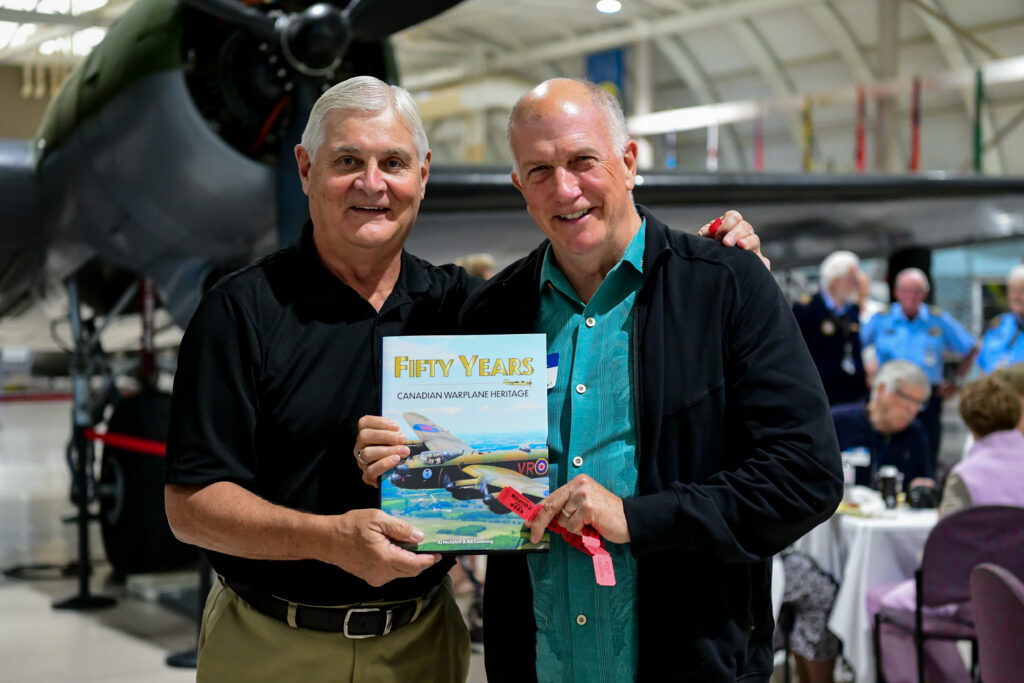

Several details for this story were taken from Fifty Years: Canadian Warplane Heritage, co-written by Al Mickeloff and Bill Cumming. A limited run of 2,000 copies was printed earlier this year, selling out in less than six months.