Estimated reading time 15 minutes, 44 seconds.

On Nov. 22, 2016, the Canadian public was informed of an urgent “capability gap” within the fighter jet force structure of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

After analyzing the situation, Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan and other senior government and military members held a press conference that day to announce a three-part plan designed to guide the replacement process for Canada’s greying fleet of CF-188 Hornets.

“We will launch a wide open and transparent competition to replace the CF-18 fleet,” Sajjan told the press. “The first step will begin in the months ahead. In addition, we will enter into discussions immediately with Boeing for a fleet of 18 Super Hornets to address the capability gap. Third, the Canadian Armed Forces will implement a range of new measures to extend the life of the current CF-18 fleet.”

Canada’s CF-188 Hornets–which first entered service in 1982–have had their airframes and missions systems upgraded periodically to keep them safe and operationally relevant, but it’s been clear for years that a replacement must be found.

What hasn’t been as clear is why, according to the Canadian government, the situation is now so urgent as to prompt immediate negotiations with Boeing Defense for the purchase of an interim fleet of 18 Super Hornet fighter jets.

Why could Canada not launch an open competition now and make do with the existing Hornets until a successor was named?

After all, even RCAF Commander LGen Mike Hood testified to the Senate Committee on National Security and Defence on Nov. 28, 2016–nearly a week after the press conference–that all 76 Hornets are able to safely fly until 2025 or later, having been upgraded to stay “active and relevant” until a final replacement could be found through an open competition process.

So why the urgency? According to government sources, it’s all a matter of policy interpretation. They say that currently, Canada cannot simultaneously meet its commitments to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) while maintaining its own sovereignty. The word “simultaneously” is the key here. In other words, if those three priorities came knocking at the same time, Canada would be unable to respond effectively.

With 76 aging CF-188s operating at a serviceability rate of roughly 50 per cent, Canada’s current ability to meet its obligations in a meaningful way would be severely limited.

“We should never have allowed this to happen in the first place,” said one source. “We enjoy the protections of NATO [and NORAD] and it would be irresponsible if we could not provide capability because we are stretched too thin.”

And, according to Sajjan, that’s a reality the current government is not prepared to “risk manage”–as previous governments are accused of doing–in the hope that the worst case scenario will never unfold.

“We have an obligation to have a certain number of fighters ready for NORAD and NATO. However, the number of mission-ready planes we have today is less than the obligations to NORAD and NATO taken together,” he said. “The objective of our government is to fix that gap as soon and as effectively as possible.”

And so, without further ado, the Canadian government launched discussions with Boeing–negotiations that were underway at the time of writing in mid-January 2017.

Taking heat

The decision to purchase an interim fleet of Boeing Super Hornets has been criticized by the press and former military officials alike.

They cite many reasons why the plan doesn’t fly–not the least of which is that the Liberals were elected on the basis of a platform which promised “an open and transparent competition” to replace the CF-188 Hornets. Instead, the government’s decree that it will sole-source the purchase of an interim fleet seems like anything but open and transparent.

Not to mention that cost projections for 18 Super Hornets have remained murky so far–in response to reporters’ questions, Public Services and Procurement Minister Judy Foote only said, “The cost must be acceptable to Canada. We must sit down with Boeing and see what they can provide–we want the best service and [the best] capability. If a fair price is negotiated, that price will be made public.”

Indeed, Parliamentary Budget Officer Jean-Denis Fréchette has given the Department of National Defence until Jan. 31 to comply with a request to provide cost estimates for the interim Super Hornet acquisition.

Critics also believe a Super Hornet purchase now stacks the deck in favour of the Boeing jet during the future competition to replace the entire fleet, which is expected to take up to five years from the release of the government’s Defence Policy Review, expected this spring. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has gone on record several times with his doubts about the F-35, an aircraft he said while campaigning that Canada would not buy if the Liberals were elected.

Capability-wise, there are accusations that the government is wasting Canadian taxpayer money on the Super Hornet, a so-called fourth-generation “dinosaur” that pales in comparison to the promised abilities of Lockheed Martin’s stealthy, fifth generation F-35 Lightning II.

Finally, if Canada did buy the F-35 following the competition process, then that leaves us with the question of what to do with the Super Hornets? They will still be young jets–certainly by CF-188 Hornet standards–but operating a mixed fleet will be costly and inefficient for an air force as small as Canada’s, critics say.

The right choice for right now

Generally speaking, the selection of any aircraft is driven by a country’s mission profile.

“Your needs are determined by your missions,” said another source who also requested anonymity. “The public needs to understand how these 18 new aircraft will be able to address the need to meet our NATO and NORAD missions concurrently and why we therefore need more aircraft.

“There’s been no change in policy. Our ability to respond to those commitments concurrently with adequate numbers of aircraft and people has become increasingly difficult over time due to such things as the Forces Reduction Program, the CF-188 modernization program, and the age of the CF-188 resulting in decreased serviceability.”

The addition of 18 new Super Hornets to the existing fleet of 76 CF-188s will give the air force greater latitude to meet both discretionary and non-discretionary missions.

As one source said, “The RCAF must manage these commitments, but it’s up to the government to ensure they can do so. The Super Hornet is at the FOC (full operating capability) stage versus IOC (initial operating capability), like the F-35.”

To those who claim the Super Hornet program is winding down, Boeing says otherwise. Roberto Valla, the company’s vice-president of global sales, told Skies that the U.S. Navy will be flying the Super Hornet [alongside the F-35] through 2040. “We are working with the Navy on a robust service life extension plan and continually inserting new capabilities to keep the aircraft relevant for decades to come,” he said.

And in the U.S. Marine Corps, the F-35 is set to replace the legacy F/A-18 Hornets and the AV-8B Harrier.

An interim fighter purchase will boost the Canadian fighter fleet by some 19 per cent. It will also increase capability significantly, with the Super Hornet presenting some unique benefits.

“That aircraft works best with our current infrastructure and is the quickest way to get capability,” emphasized one source. “The Super Hornet comes with known capital and sustainability costs and is ready to go now while the F-35 is in the system design and development (SDD) phase.”

A memo dated Aug. 9, 2016, and prepared by J. Michael Gilmore, director of the Operational Test and Evaluation Directorate of the U.S. Department of Defense, indicated that although the U.S. Air Force declared IOC with the Block 3i configuration of the F-35A, the fighter would not hold up against the criteria of initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E).

“If used in combat, the F-35 in the Block 3i configuration, which is equivalent in capabilities to Block 2B, will need support to locate and avoid modern threats, acquire targets, and engage formations of enemy fighter aircraft due to outstanding performance deficiencies and limited weapons carriage available….,” wrote Gilmore.

In other words, if deployed this past summer, the F-35 would have necessarily been accompanied on a combat mission by fourth generation fighters.

Gilmore also pronounced the program “on a path toward failing to deliver the full Block 3F capabilities for which the Department is paying almost $400 billion by the scheduled end of System Development and Demonstration (SDD) in 2018.”

But while doubts have clearly been expressed about the F-35, sources who spoke to Skies said the program is trending well, with costs coming down and capabilities coming up. However, “we understand the capabilities of the Super Hornet today; the F-35 brings its IOC and what it can do today.”

In other words, they believe it’s not a question of which fighter is ultimately the best fit for the Canadian mission profile–it’s a question of which interim jet is the right choice for the country right now, in the face of what the federal government deems an unacceptable capability gap.

Performance in the field

The F-35’s claim to fame has always been its stealth capability, the argument being that if the enemy can’t see you they can’t hurt you.

But while a stealthy airframe is undoubtedly an advantage, “an element of stealth with a healthy electronic warfare capability is perhaps a more balanced approach,” said one source.

And, while Lockheed Martin works diligently to perfect the F-35, countries like Russia and China (as well as the U.S. and its allies) are also working hard to improve existing low-frequency radars for early-warning purposes and to get a general idea of where stealth aircraft are operating. While these radars may not be able to pinpoint stealthy aircraft with enough accuracy to fire upon them, they are reportedly able to pick out their general location.

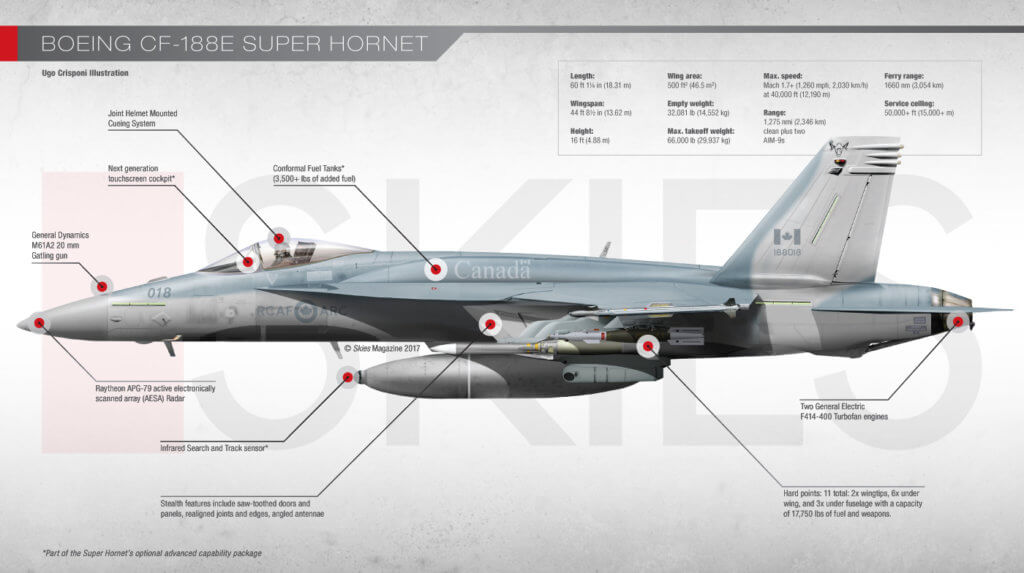

In the meantime, the Super Hornet’s upgraded AESA (active electronically scanned array) radar represents an “exponential leap in technology needed for current and future missions,” said Boeing’s Valla.

That AESA radar has been called a “force multiplier” by some sources, who say that just one Super Hornet will be able to see and share valuable data with the classic CF-188 fleet through a datalink capability.

Another knowledgeable source told Skies that the Super Hornets’ AN/APG-79 AESA radar hardware is essentially equivalent to the AN/APG-81 on the F-35.

“Radars are the same,” he said. “They use different algorithms to produce information for the pilot. Other onboard sensors such as FLIR (forward-looking infrared) and IRST (infrared search and track) complement the radar.”

He added that the U.S. Navy’s Super Hornets and EA-18G Growlers (an electronic warfare variant of the Super Hornet) are all tied into the Navy’s digital network, which feeds each aircraft a steady stream of data from a variety of sources, including satellites and unmanned platforms, for a complete and comprehensive picture of the operating environment.

“This is the ultimate sensor fusion,” said the source. “The F-35’s sensor fusion will come through the Navy’s digital network as well. But the Growler underpins the current U.S. Navy capability.”

Canadian Super Hornets

With negotiations currently underway, Canada will be looking to get the best deal possible in terms of equipment and support.

So what might the ideal Canadian Super Hornet look like?

“At a minimum, I think our Super Hornets should have conformal fuel tanks and the same updated cockpit as the U.S. Navy [with AESA radar],” said one source, who is also in favour of painting the traditional Canadian false canopy on the bellies of the new jets.

In an ideal situation, CF-188s belonging to one of the four existing fighter squadrons would see their aircraft redistributed elsewhere; subsequently, that unit would transform into a Super Hornet squadron. Such an arrangement would utilize existing personnel to maximum effect.

Our sources say Cold Lake is their preferred location for Canada’s new jets, with a squadron hopefully achieving FOC within two years of Super Hornet delivery, which could be as early as 18 to 24 months from contract signing.

“I’m assuming 12 [jets] operational on the line at any given time, 24 pilots, and 200 to 250 technicians. Cold Lake is the ideal spot with the training range and AETE [the RCAF’s Aerospace Engineering Test Establishment] on site,” said one contact.

When asked about his recommendation for Canada’s future fighter, post-competition, he said a mixed fleet would be a “luxury” because no one aircraft can do everything well.

“I’m a dreamer, but I think if we had a mixed fleet of Super Hornets and F-35s that would be ideal.”

For its part, the Super Hornet works with Canada’s existing infrastructure (including short runways in the far North), is compatible with our existing air tanker fleet, and in fact brings a built-in tanking capability of its own. Plus, with close to 60 per cent commonality with the legacy CF-188 Hornet, the transition for both pilots and maintainers should be smooth.

As it stands today, the F-35 shows promise but it would need upgrades to operate from the RCAF’s established forward operating locations and currently could not be refuelled by Canadian air tankers.

In addition, an important factor is the deployability of the aircraft, said one source. “The F-35 is designated top secret so that calls for extraordinary operating locations. It’s not a problem for a country like the U.S., but how would a smaller country like Norway deploy the F-35 on an operational mission? They’d have to go to a designated U.S.-approved area. It is a consideration.”

Of course, a mixed fleet approach could cost Canada more money, and therein lies the stumbling block in this “blue sky” scenario.

In any case, an open competition that pits Canada’s identified mission profile and priorities against demonstrated aircraft performance and well understood capital and acquisition costs is undoubtedly the best way to select the country’s future fighter fleet.

And, with that competition expected to take five years, the final decision will fall into the hands of the next government–Liberal or otherwise.

One other thing is a certainty, too. Canada will need a lot more than 65 new jets–the number of F-35s originally proposed by the Harper Conservative government–to address its now-urgent fighter jet capability gap.

Lisa Gordon is editor-in-chief of Skies magazine. Prior to joining MHM Publishing in 2011, Lisa worked in association publishing for more than a decade, overseeing the production of custom-crafted trade magazines. Lisa is a graduate of the Ryerson University Journalism program.

Yes, I certainly have a comment as a Canadian Taxpayer, I really do not care what intercepter the Govt buys but let’s do it. If they keep putting it off for another 5 years if and when the govt changes it will be put off again. For Christ’s Sakes you are paid good money to make decisions so MAKE a Decision and buy the rest of the aircraft so we can at least protect our Country. We still need choppers to replace those relics we call SeaKings and that decision hasn’t been made yet.Get off your asses and make a decision.

My young daughter’s could make a decision faster than these so called Politicans

The new Administration in DC is seriously looking into a new further upgrade.. an “ultra Hornet” F-18H for the Navy.