Current Hall of Fame members join new inductees and next-of-kin representatives for a group photo. Front row, left to right: Millie MacLean, who participated in receiving the Belt of Orion Award for Excellence for the Royal Canadian Naval Air Branch. Her late husband, Bud MacLean, was instrumental in nominating the Air Branch by the Canadian Naval Air Group. Next to her are new members of the Hall of Fame, Fred Carmichael and Kathy Fox; Byron Cavadias (inducted 1996); Victor Bennett (inducted 2013); and Dick Richmond (inducted 1995). Back row, left to right: Jim McBride (inducted 2015); Larry Milberry (inducted 2004); Donna-Lee Waymann, representing her late father, Ross Lennox; Paul Baiden, president of the Canadian Naval Air Group, representing the Royal Canadian Naval Air Branch; Saxon Shenstone, son of the late Bev Shenstone. Rick Radell Photo

Newly inducted members of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame (CAHF) offered amusing insights about their early careers during the 43rd induction ceremony, held June 9 at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa.

Inductees are selected by what Tom Appleton, outgoing chairman of the Hall of Fame, described only as an “anonymous team of distinguished Canadians, each a recognized expert in his or her field.” That can also be said of the four newest inductees, including the two still living: Frederick James Carmichael and Kathleen Carol Fox.

Carmichael, born in Aklavik, N.W.T., recounted a night flight to Edmonton as a teenager with one of his mentors aboard a Stinson 108 Voyager. “When I saw all the . . . city lights for the very first time in my life, coming from the North, I thought they must be stars and thought, ‘What are we doing? Are we flying upside down or what?’ And that is true, I tell you.”

Fred Carmichael of Inuvik, N.W.T., a pioneering pilot in Canada’s north, still flies his own aircraft 60 years after getting his first pilot’s licence. Here, he makes his acceptance remarks after being installed as a member of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. John Chalmers Photo

Fox, a Montrealer who also acquired her passion for aviation as a teenager, told the packed audience that she couldn’t afford flying lessons at the time. “I took up skydiving because I figured that was a way of getting up in the air; once I learned how to fly and land the airplane, I quit jumping out of them!” When the laughter subsided, she added that she had still wanted to fly commercially. “But I couldn’t—so I became an air traffic controller so I could tell pilots where to go!”

Carmichael, who has flown for 60 years and still does so recreationally, worked hard to save enough money to pay for flying lessons in Edmonton. He earned his private pilot’s licence at the age of 20 and become the first Aboriginal pilot from the Arctic region.

His first aircraft, a Voyager which came with floats and skis, followed in 1956. He founded Reindeer Air Service in 1959, rapidly expanding to 15 aircraft. In 1998, the local air strip he helped to develop was formally named Aklavik Freddie Carmichael Airport (VYKD), and a Cessna 170 Carmichael once owned is now mounted there as a wind-direction indicator.

Fox was introduced to flight by her uncle in 1967. She went to McGill University in Montreal, where she took a BSc and was introduced to skydiving. Before quitting, she had done more than 650 jumps, including at international competitions.

During her jumping days, she became a Transport Canada air traffic controller in Quebec in 1974, and finally acquired her private pilot’s licence in 1978. Commercial, airline transport and instructor tickets followed, as did multi-engine and instrument ratings. Then there was a Master’s in business administration, again at McGill.

She returned to ATC in 1987, moving quickly into management in Ottawa and then to Nav Canada, where she became vice-president of operations. Fox retired from there in 2007; and, while a member of the Transportation Safety Board, took a Master’s degree in human factors and systems safety from Lund University in Sweden. In August 2014, she was appointed to a four-year term as TSB Chair and, with more than 5,000 flying hours logged, including participation in Canada’s precision flying team, she still instructs part-time at Rockcliffe Flying Club, sharing a runway with the museum that hosted her CAHF induction.

“It’s very humbling to be recognized in the same breath as so many Canadian aviation pioneers,” Fox told her audience. “At the same time, I feel a tremendous validation for a lifetime of practising what I love most.”

Two other inductions were posthumous: Beverley Strahan Shenstone and William Ross Lennox, who died in 1979 and 2013, respectively.

Mary Oswald, editor of The Flyer, the newsletter of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame, presents a gift from the Hall to Saxon Shenstone, who came from England to accept his late father’s induction as a member of the Hall. John Chalmers Photo

Toronto-born “Bev” Shenstone had a distinguished career, including designing the signature elliptical wing of the Spitfire while working for Vickers Supermarine in England. The first Canadian to graduate with a Master’s degree in aeronautics from a Canadian institution, he studied at the University of Toronto while a Royal Canadian Air Force provisional pilot officer.

Before moving to England, he had worked for Junkers in Germany and eventually returned to Canada, refining his reputation as an aerodynamicist on various RCAF and National Research Council projects. In 1946, he returned to Toronto as general manager of A.V. Roe Canada Ltd., overseeing development of the Avro C-102, North America’s first jetliner and the CF-100 Canuck interceptor.

Then it was back to England and British European Airways (BEA), where he played a key role in developing the Vickers Viscount, the first turpoprop airliner, and introduced helicopters to BEA operations for North Sea oil platform service.

Shenstone also worked on early development of the de Havilland DH-106 Comet, the world’s first commercial jetliner (which flew just 13 days before its Avro competitor), and the program which eventually yielded the supersonic Anglo-French Concorde.

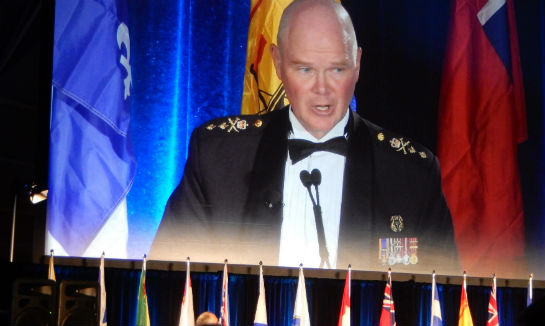

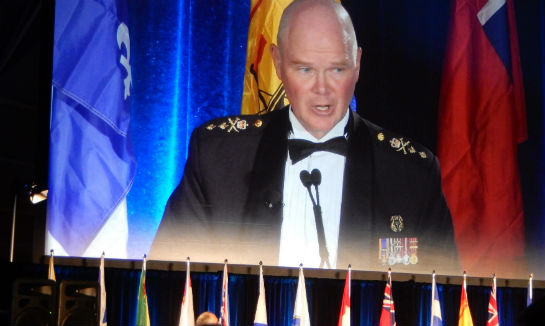

RCAF MGen John Madower served as guest presenter and speaker at the annual induction ceremonies of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame honouring outstanding contributions to Canadian aviation. John Chalmers Photo

Lennox began his flying career as an RCAF instructor in 1942 before joining an Operational Training Unit and then flying Douglas Dakota DC-3s to transport wounded soldiers to Britain from Germany, France, Greece and Belgium.

Discharged in 1946, he became a flight instructor at the Flin Flon Flying Club in Manitoba, while also ferrying geologists, prospectors and miners into the North, eventually starting Hudson Bay Air Transport. He went to Okanagan Helicopters in 1953 for training on Bells, transitioning to Sikorsky S-55s used to build the DEW Line and the Mid-Canada Line.

With 10,800 hours logged, Lennox joined United Aircraft of Canada, which became Pratt & Whitney Canada (P&WC) in 1975, to test Sikorsky Sea Kings. He was the only pilot to fly all 41 of the CH-124 versions acquired by the Royal Canadian Navy, and was chief test pilot and head of flight operations until retiring in 1982. He logged more than 23,400 hours in 63 aircraft types.

Lennox was involved with Okanagan Helicopters’ joint venture with BEA to service the North Sea rigs, flying S-61N variants of the Sea King. His exploits included an unescorted multi-layover flight to Oslo, Norway, over two weeks in May 1965.

The only Canadian in the late 1960s licensed on the Sikorsky S-64 Skycrane, Lennox joined Erickson Air-Crane—which had acquired manufacturing rights to the S-64—when he retired from P&WC. Unwilling to give up flying after leaving Erickson, Lennox flew charters on Great Bear and Great Slave Lakes until 1993, involving a return to his DC-3 roots.

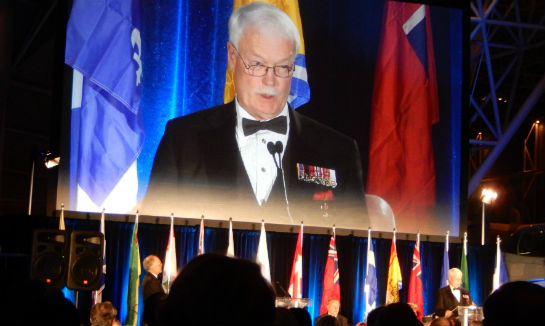

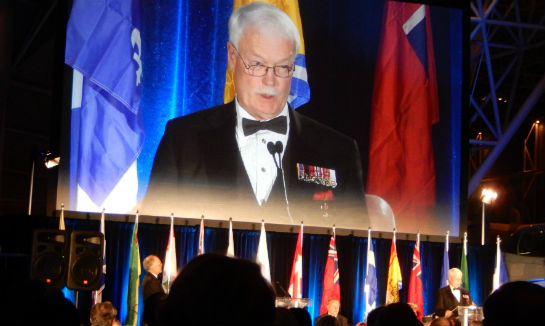

Paul Baiden of the Canadian Naval Air Group, which nominated the Royal Canadian Naval Air Branch for the Hall’s Belt of Orion Award for Excellence, makes his acceptance remarks for the Air Branch. John Chalmers Photo

The final event at the CAHF induction ceremony was the awarding of the coveted Belt of Orion to this year’s recipient, the Royal Canadian Naval Air Branch (1945-1968). For 23 years, the organization was a key element of national maritime security with its aircraft carriers and fleet of fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft. Among its many accomplishments, the Air Branch pioneered the operation of anti-submarine maritime helicopters from the decks of small warships. This necessitated the development of the world-renowned “beartrap” helicopter haul-down landing system, which was subsequently adopted by other navies around the world.