They don’t call it Hercules for nothing. Named for the heroic demi-god son of Zeus, the Lockheed Martin CC-130 saw its first Canadian deployment half a century ago. In its latest iteration, the Super Hercules J model, the aircraft is the backbone of this country tactical airlift capability, with the capacity to carry up to 92 combat troops (or 128 passengers) and conduct search and rescue missions. It is capable of short takeoffs and landings on austere runways in any weather, including hot and high in Afghanistan, where it supported NATO ground forces, as well as elsewhere on a range of humanitarian missions.

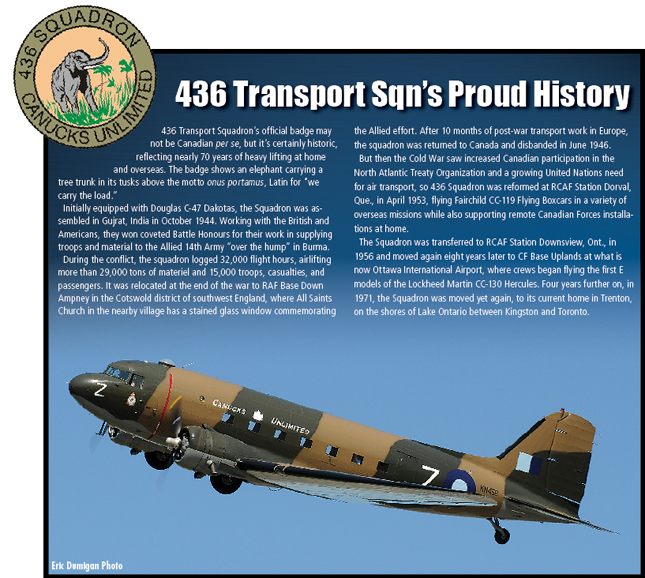

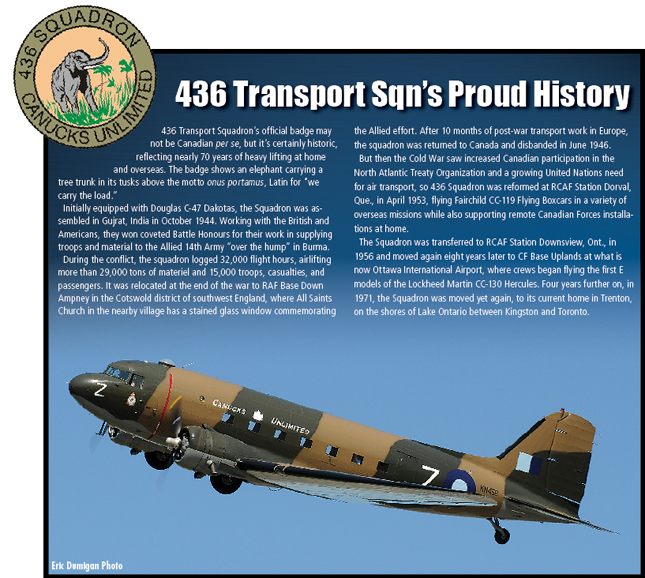

Canadian Forces Base Trenton, Ont., 436 Transport Squadron, which is the largest in the Royal Canadian Air Force with 368 uniformed personnel, took delivery of its first J model in June 2010. Lieutenant-Colonel Colin Keiver, the squadron commanding officer, is looking forward to the arrival of the 17th and final aircraft this coming summer, hopefully before his two-year assignment is up. Keiver and senior members of his squadron gave generously of their time during a recent Canadian Skies visit to the base, and their appreciation for the aircraft they fly and maintain was evident.

This airplane and what it can do is remarkable, said Keiver, an Albertan who has nearly 4,000 hours on the Hercules and whose experience, during an exchange posting with the United States Marine Corps, prompted his assignment as director of safety and standardization at the first USMC squadron to deploy Js. It has exponentially increased Canada options as a nation. We joke in the CC-130 world that we’re always first in and last out. It true. . . . We will continue to grow in our ability to support multiple operations simultaneously.

Not the Same Hercules

The initial challenge for the RCAF when it was still Air Command was the sheer number of people who had to be trained on the latest model from Lockheed Martin production line in Marietta, Ga.

It is a new airplane, Keiver explained. It a different crew complement; maintenance practices and procedures are different; it very much an electric airplane. If he does have a gripe, it about the aircraft designation. They should have called it a C-131 because it would have tweaked everyone to just how different it is.

Legacy models had a four-member flight deck where the crew spent a lot of time managing various systems, a process Keiver said took a lot of your limited brain bucket. The J manages most of that in the background, resulting in a dramatic increase in mission effectiveness. Now, instead of managing the airplane, I’m managing the mission and the situation around me. I was doing that in the old airplane but not to the same extent.

Like most modern aircraft, the J has a digital cockpit, but the heads-up display (HUD) is the primary flight instrument, a potentially spooky situation for any visitor in that the commander and pilot seem to be simply sitting and staring through the glass HUD. Each is seeing the same information. In demanding environments such as complex low-level missions which can require night-vision goggles, and more so when there is an enemy to consider, it has proven itself repeatedly.

I won’t say it easier; it different, Keiver said. There still a requirement to be a hands-and-feet pilot, but you also now have to be very good at monitoring what going on. One of the critical tasks is our ability to effectively manage and prioritize the information that the airplane is giving us . . . all the time. That information was always there with the legacy CC-130s, but some newcomers to the Js have struggled with the transition, believing that they need the same level of detail to do their job. The difficulty in those situations is that some pilots get task-saturated to the point where their decision-making decelerates, but they tend to come around to the new approach.

Once the aircraft is back on the ground, myriad technological advancements incorporated into the J mean that before any maintenance is considered, there is a huge post-mission data download from the onboard computers.

With the old one, you took a hammer and started beating on it right away. We’re a year and a bit into the transition and my sense is that we’re coming out the other side. Keiver followed that up with a chuckle: You know, confidence is that feeling you always get just before you have a problem . . . but it been a very interesting experience.

Even air drops, a strong suit in the J versatile deck of cards, have changed. They’re essentially controlled by the aircraft itself, automatically dispatched through the flight management system or what Lockheed Martin calls the communication, navigation, information management unit. Assuming all data are input correctly, the box crunches the numbers, runs the cargo deck lights and locks and, at the appropriate time and altitude, chucks out the load. In most cases, the autopilot is coupled as the aircraft crosses the drop zone.

Reliability and Predictability

Keiver used most of late 2010, once the first few aircraft had been delivered, to build up his crew force and maintainers. At the time of the Canadian Skies interview a year later, he was working towards transitioning out of Afghanistan. He sent his first J overseas just before Christmas 2010, while bringing one of two H models home. That meant that Canada had an H and a J in-theatre until last spring, before a second J-for-H exchange occurred. At one point last February, a CC-130J left Trenton with just 14.6 hours on the clock and with total crew time on Js of less than 300 hours, in support of Task Force Libeccio, the Libyan mission. Keiver agreed with the notion that it was a green airplane with almost a green crew and that although the mission could have been flown with a legacy model, it would have been somewhat more challenging because the Js require less front-end effort to get the same result.

We’ve pushed the envelope significantly, Keiver said, anticipating that the fleet will have logged 5,000 hours by February or March this year. At the time of the interview, he had one aircraft in Afghanistan, one in Italy and three or four at Trenton, and one had recently returned from Operation Box Top, a supply run through Thule, Greenland, to CF Station Alert at the top end of Ellesmere Island. The CC-130J capabilities mean that the RCAF no longer needs supplementary commercial airlift for some of Box Top.

Exceptional! Keiver said. It changed the way we approach operations. . . . In the old fleet, we used to spend so much time thinking about what ifs: what if this airplane breaks and there a ripple effect?’

We flew up there for two weeks straight and only lost three missions because of aircraft unserviceability. That what you get with a new airplane; you get reliability and predictability. It has significantly expanded our planning envelope. It has made us infinitely more flexible and adaptable because we know the airplanes will be there when we need them.

Flight training on the Js is such that officers assigned as aircraft commander and co-pilot have the same qualifications and can even have the same rank. The only difference is mainly how decisions are made, the responsibility piece as Keiver put it. The aircraft commander is the final authority; it the chain of command. With the old airplane, we had a hierarchy. I would argue, depending on the flight engineer, that it went: aircraft commander, flight engineer, co-pilot and then the loadmaster in the back at the bottom of the pyramid.

That dynamic has shifted in that some key technical skills have migrated to the loadmaster, who will go out at the start of a mission and power up the aircraft to initialize critical systems.

He needs that aircraft up and running even to load it, Keiver said, explaining that all the pilot has to do is sign off on a weight and balance sheet. The way the loadmaster interacts with the airplane is all recorded in the box. Paperwork that was necessary with the legacy Hercs has been effectively eliminated.

Getting Up to Speed

While he simplified HUD-centric flying process as keeping the solid circle inside the hollow circle on the HUD, Keiver added that the training has not been as straightforward as might have been expected. It has taken us a little longer at the front end to get guys up to speed, but once we have them and send them on operations, these young kids are incredibly capable. Unlike me, these young guys understand these computers. This is second nature to them; it makes complete sense to them and they show us old guys things we would have never thought of. When Canadian Skies suggested, Enough of the young/old stuff, Keiver laughed. But it true! It remarkable to see their ability to manipulate systems rapidly.

If there a limiting factor in the CC-130J program, it the number of qualified personnel. Lockheed Martin has so many J customers and the only schoolhouses are operated by the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC), the U.S. Air Force (USAF) and its British and Australian counterparts. Those facilities are all in demand by foreign customers. Canadians travel mainly to the USAF schoolhouse in Little Rock, Ark., but a few go to Lockheed Martin in Marietta. The latter, however, only gives them type conversion, not mission qualification, which requires more training when they rotate back to Trenton. In contrast, those who spend at least five months in Little Rock require little, if any, further polishing. They’re switched on; they know this airplane and they know the mission, Keiver said.

In contrast to some other Canadian defence acquisitions, the CC-130Js are minimally customized in that they have secure satellite communications gear, the extended service life wing mandated for U.S. Special Operations, and lower-fuselage protection against rock damage on austere strips.

There not very much that uniquely Canadian and that one of the reasons we’ve managed to get it into operation so quickly. We tweak it a little bit when we get it here, but not very much, said Keiver.

A couple of elements are distinctly un-Canadian: a USAF Major and a USMC Captain on exchange. The former is 436 Squadron chief training officer and the latter was about to become chief check pilot [at the time of the interview]. Keiver credits the two Americans for their assistance with introducing the J model to the squadron. If it had not been for those two, with their 1,000-plus hours on type, we would not be where we are today, he said. For that first six or seven months, they were the only instructor pilots I had.

Having never finished an engineering degree (probably a service to aviation, he says), Ken Pole has had a lifelong passion for things with wings. The longest-serving continuous member of the Parliamentary Press Gallery in Ottawa, Ont., he has written about aerospace in all its aspects for more than 30 years. When not writing, Ken is an avid sailor, diver and photographer.