Estimated reading time 14 minutes, 57 seconds.

Brandon Robinson’s Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Top Aces fighter pilot exploits compare to those of a protagonist in a blockbuster movie. After graduating from the Royal Military College of Canada with First Class Honours, his career quickly skyrocketed from frontline fighter squadron to being selected for the prestigious Fighter Weapons Instructor Course (FWIC) – the Canadian version of Top Gun. He obtained an MBA at Royal Roads University, and then did a tour in Ottawa where he “managed over $4 billion in procurement projects for the Fighter Force.”

He spent the next few years instructing for FWIC. “Think ‘Viper’ from the movie Top Gun,” he laughed.

“I then completed our Joint Command and Staff College program for those flagged for senior leadership.”

While instructing for FWIC, Robinson earned the CF-18 fighter pilot instructor role at 410 Squadron in Cold Lake, Alberta, leading into oversight of CF-18 Fleet Tactical Standards, and then onto senior project management with a deputy director role in multiple Air Force projects.

Robinson is modest. He credits his competitive nature “and a lot of luck” for his success.

“I fully acknowledge that without exceptionally talented and competitive friends, I would not have passed, let alone have been fortunate enough to fly jets,” he told Skies.

He found Military College to be physically and emotionally demanding, having a way of teaching you your limits and how to “be at peace with them.” Despite the challenges, he was one of the top five engineers in the program all four years.

For Robinson, aviation was innate. His grandfather, RCAF Capt Eric Robinson was a Second World War bomber pilot. His father, Brian Robinson, began flying at the age of 14, but his hopes of joining the Air Force were grounded when he learned his vision wasn’t good enough.

“My father was very young when he and [my grandfather] built from scrap metal what is now a family airplane — an old RC-3 Republic Seabee aircraft.” Brian retired from his day job to turn the family hobby into a successful custom aviation engineering business.

There was always “an army of airplanes” in and around Robinson’s home.

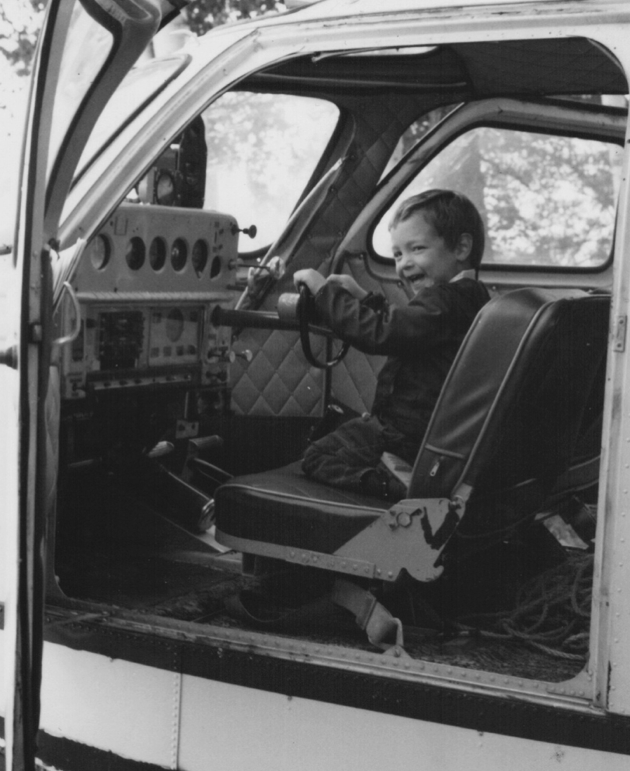

The first time Robinson piloted a plane, he was three years old. His grandfather let him sit in the seat in front of him. “I couldn’t sit. I had to stand,” he laughed. “He said, ‘OK, you have control, so take us over there.'”

That experience “made an imprint” for Robinson. After high school, much to his “mother’s chagrin,” he joined the RCAF to “fly fast jets.”

After military training, “there’s a big [graduation] ceremony where they hand out the slots, and I remember looking at the card and seeing the CF-18 symbol on the bottom,” he said. Internally, he was bursting.

Not surprisingly, when asked about the memorable moments of his career, he said it’s difficult to choose.

Robinson recalled, after being on the Squadron for just three months in Bagotville, Quebec, he was deployed to Hawaii for a joint exercise with the U.S. Navy.

“The U.S. Navy has this big exercise, and the Canadians were asked to go,” he said. “So, we ferried CF-18s across the country, from Quebec to Comox, British Columbia. We overnighted, met up with an aerial refueler and then the next thing I know I’m in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, tanking off a refueler. There’s a portion where, if you can’t get gas, you’re going to have to eject because you can’t get back to land. I’m a 27-year-old kid who only has 200 hours of experience in this CF-18, and I’m over the middle of the ocean thinking, ‘OK, you better make this happen.’ It’s not the easiest maneuver either,” he laughed.

Robinson shared the story of how he earned his call-sign: Repo. “I was flying, and my left engine essentially blew up; one of the main turbine hubs fractured. It severely crippled the aircraft, placing it into a reversionary control architecture. The engine was destroyed, and the aircraft was on fire,” he said.

After 10 “very long seconds” of being “out of control,” he “dealt with the fire” and regained control.

“I was able to land it safely back at the base. However, it was too badly damaged to fix. So, the joke was that the government had to repossess or repo it,” he laughed. “The damaged engine almost fell out when I landed.”

He remembered flying low-level over the ocean while “shooting missiles at drones and dropping bombs on remote-controlled moving ships; being in front of 100 angry fighter pilots leading a NATO coalition strike mission; [and] early morning departures over Torrey Pines in California to dogfight over the ocean.”

In 2018, with 20 years of service and a list of neck and spine injuries in his rear-view, he knew it was time to find adrenaline elsewhere. “You can’t pull seven-and-a-half Gs for 20 years without hurting a few things,” he laughed.

Leaving, he admitted, was a difficult decision, but entrepreneurship was also on his radar.

The kid that grew up in rural Ontario, Canada, with an “army of airplanes” at his disposal and a military career most would envy, headed out to his next call of duty. He joined forces with his father to start Horizon Aircraft, an aerospace startup that is currently developing the Cavorite X5 — a new eVTOL (electric vertical take-off and landing) design for the urban air mobility market.

Horizon has been developing the Cavorite X5 for the past two years. The concept for the X5 came from the company’s initial prototype, the X3 — an amphibious design with a hybrid electric power system. “When we were asked to push the performance even further, we naturally began investigating distributed electric propulsion and the potential for eVTOL modification of the core X3 concept,” explained Robinson. “That’s how the X5 was born.”

The five-seat Cavorite X5 is powered by an electric motor coupled with a high-efficiency gas engine, but is ultimately built for fully electric flight. Horizon is building the aircraft to fly at speeds up to 350 kilometers per hour, with a 450-km range.

The focus is to produce an aircraft “able to do real work in harsh environments,” including disaster relief, medevac, air cargo and personnel transport.

Today, Robinson has his hands full with multiple patents pending, including a “fan-in-wing design” that would allow the Cavorite X5 to fly either like a conventional aircraft or an eVTOL when required. The X5 “flies like a normal aircraft for 99 percent of its mission,” said Robinson. The wing design “allows the aircraft to return to normal wing-borne lift after its vertical portion is complete; when moving forward, the wings close up and hide the vertical lift fans.”

Horizon is working towards a large-scale prototype it hopes to have flying by the end of 2021.

Robinson has become comfortable fielding questions based on skepticism. He’s built an army of support from his highly-skilled network, including Virgin Galactic test pilot and close friend, Jameel Janjua. “Our team is extremely experienced, formed out of my father’s previous custom aviation engineering business. We also have an individual leading the technical development who has designed, built and tested two novel aircraft designs from scratch.

“We see many eVTOL concepts, and we have set ourselves apart by putting engineering first — producing a safe, tough and capable machine that is simply a better way to build an airplane,” he added.

Despite the obstacles created by the global pandemic, Horizon Aircraft is aiming to fly the sub-scale prototype in a few months.

I am so glad to see a Canadian show our friends to the South that we have shaw it takes and more if required . I salute you sir for making me proud to be a Canadian and hope your business venture becomes a thriving success

Proud to be Canadian, you will be a great success!

I want to work with you guys! What a magical ride you are on. No doubt the challenges are many but you have seen challenge before.