Estimated reading time 14 minutes, 22 seconds.

Editor’s note: This is part 3 of “a trip to…” series by Ted Delanghe, where the former Air Force pilot recalls extraordinary memories and lessons learned from his time spent flying over 50 different aircraft types around the world. Click to read part 1, part 2, and part 4.

Some days you wake up and pass through another day, with all in order and as it should be. Other days, you wake up and the day brings you surprises you hadn’t dreamed of. This was one of those days.

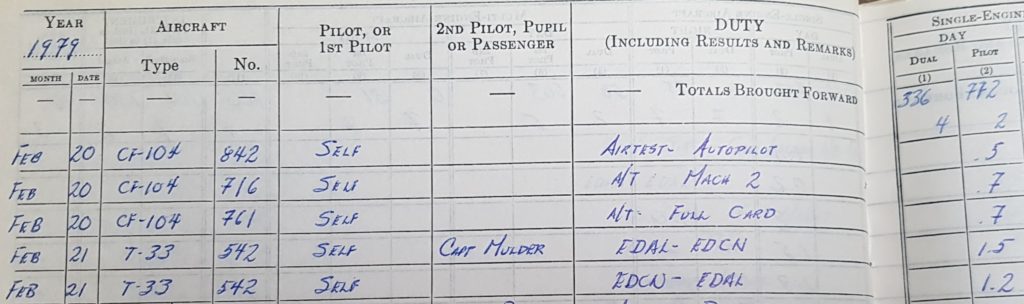

Feb. 25, 1979. I was in southern Germany, stationed at Canadian Forces Base Baden-Soellingen. That particular day, I was piloting a CT-133 Silver Star — better known as the T-Bird — with a fellow pilot in the back seat. He was attending a conference at Nauen in northeast Germany, and I was taking the opportunity to get some cross-country time in.

My passenger and I met at Base Ops where the T-Bird flight was located, the ramp lights glistening off the wet tarmac. The first step was to review the aircraft traveling logbook to ensure all flight checks had been completed, and there were no “snags” that needed attention.

Weather was typical for the Rhine Valley area at that time of year: heavy, somber overcast; continuous drizzle; a light, chilly breeze; the ground soggy; and the trees weary. It was at the height of the Cold War and everything was painted in a dark, olive shade with central European camouflage. The Schwarzwald (Black Forest) mountain range just to the east of the base was well named — heavily forested with dark green conifers. On the drive in, I could see the medieval castle Burg Windeck on the hillside just below the overcast, so that meant we had a ceiling of around 600 feet — quite comfortable for IFR flying.

Walking out to the aircraft, the sweet smell of burnt jet fuel drifted over us, courtesy of two CF-104s idling a short distance away, ready to taxi.

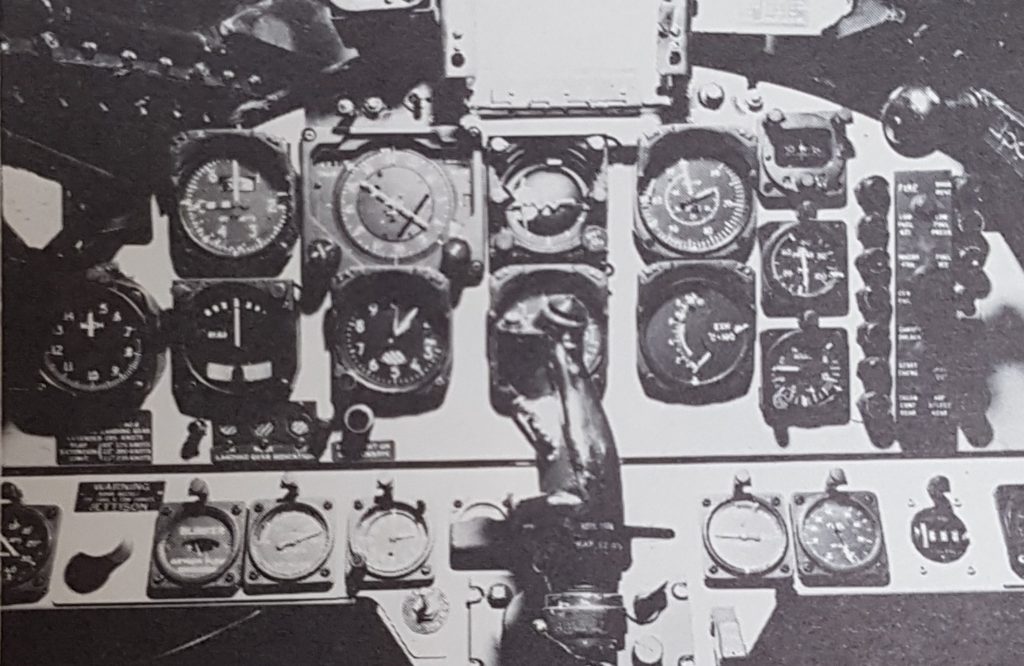

The strap-in procedure was almost automatic, having flown the T-Bird as a student, then instructor, and now overseas. Buckle the parachute harness at the bottom of the access ladder. Climb the ladder and carefully step onto the seat, then onto the cockpit floor, finally sitting down into the seat well. Connect the parachute harness to the seat pack with two clips. Feed the seat pack lanyard under the lap belt. Thread the shoulder harness to the lap belt with the quick release unit. Plug the radio chord into the helmet receptacle, attach the emergency oxygen line and the aircraft oxygen supply. Finally, don the helmet in preparation for start.

As Nauen was only about 45 minutes away, we filed somewhere around 25,000 feet cruise altitude. Cloud tops were forecast to be above 30,000 feet, and the T-Bird didn’t like to climb quickly with a full, 677-gallon fuel load. I planned on going “on top” on the return trip with a much-lightened fuel load.

We taxied out to the active just as the 104s, with afterburners blazing, departed ahead of us, quickly disappearing into the low-hanging overcast. Line up, brake release, and full throttle. Accelerate to 70 knots and aft stick; nosewheel lift-off between 80 and 90 knots; airborne between 105 and 115 knots, aiming for an initial climb speed of 250 knots indicated. With the full fuel load, the T-Bird didn’t so much take off as trundled off. But once airborne, we entered the ‘clag’ very quickly on our way northward.

We were handed over to European air traffic control (ATC) climbing through 19,000 feet; they gave us vectors direct to Nauen, so our sole navigation chore was to change the radios and navigation equipment to the appropriate frequencies as the flight progressed. That gave us time to “sight see” as we went along. It’s very strange flying in cloud so heavy that, not only can you not see the sun, you can’t see any direction you choose – left, right, up, down. Every direction looks exactly the same. There is no sense of movement, just a feeling of hanging there in the midst of a lot of grayness.

Eerie, indeed, and also not without peril. Becoming disoriented is the big danger, and it can happen quickly. In the 1990s, aviation researchers at the University of Illinois took VFR-only rated pilots in a simulator and put them into IFR conditions. On average, it took just 178 seconds for the pilots to lose control of the aircraft.

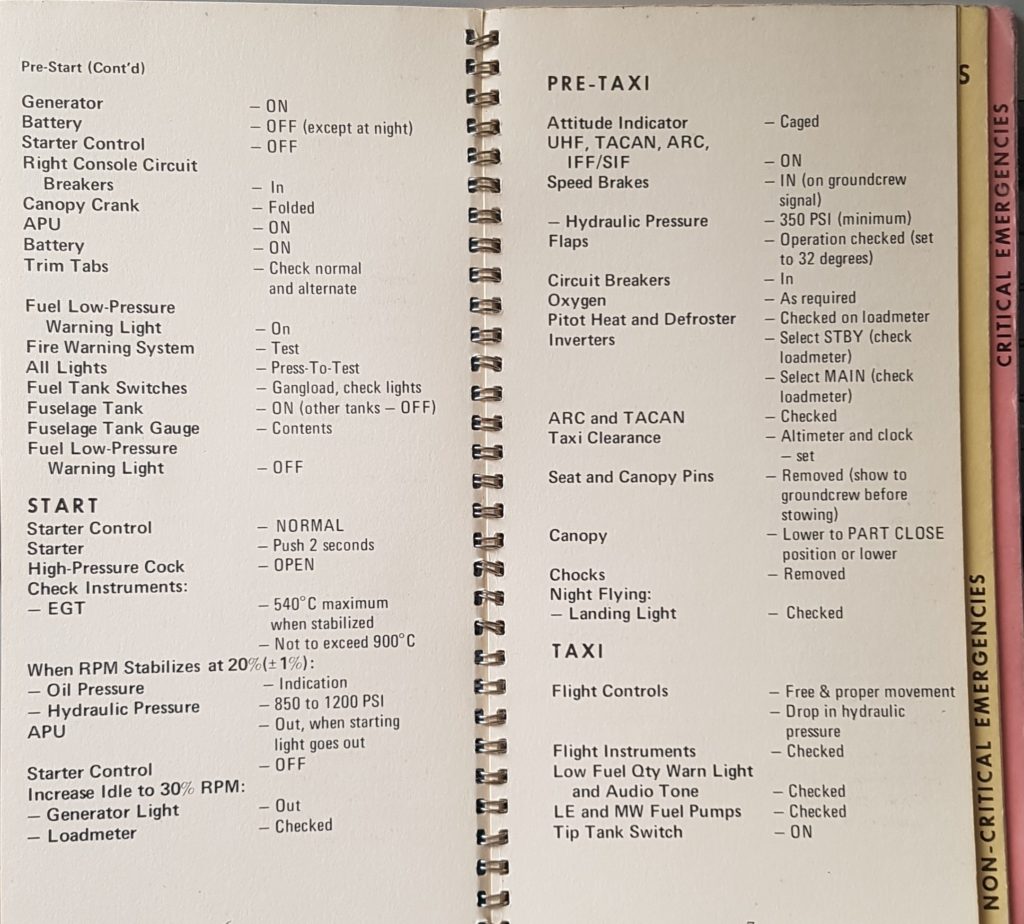

Without IFR instrumentation, the same would happen even to experienced pilots. The T-Bird instrument panel had been designed in the ‘50s, and it really showed — with little difference from the archaic and half-hazard layout of Second World War aircraft. No ergometric design here, just the feeling that the last thing the designers had thought of was ease of operation. In particular, the Bendix J8 main attitude indicator (A/I) — the heart and soul of instrument flying — was the backup on the brand-new CF-5s I had just come off before heading overseas. The J8 wasn’t pretty, but it did the job — and it was a lot better than nothing.

The arrival at Nauen was uneventful, shooting a radar approach in light of the reported 300-foot ceiling. After landing, we taxied to the main terminal where my back-seater deplaned quickly while the engine was idling. Canopy closed, IFR clearance obtained, and to the active runway where I was cleared for immediate takeoff.

That’s when the fun began.

Quickly airborne, gear and flaps up, I entered the cloud almost immediately, with ‘head inside’ fully focused on the instruments, turning southbound back to home base. ATC once again obligingly gave me a vector direct to Baden.

Rolling out on the heading, I noticed that while my pitch attitude on the A/I was correct, my airspeed was lower than the normal 250 knots, and the VSI showed a higher rate of climb than normal. Initially, I thought that was just the result of a lighter fuel load, and a bit of lackadaisical flying on my part. But something was amiss, big time. With the A/I still showing the correct pitch attitude, the airspeed continued to decay, now down to 200 knots.

And then it hit me like the proverbial ton of bricks — the attitude indicator had failed, and was completely useless from that point on. It was going to get really, really interesting.

Luckily, the extensive training in the Air Force had covered what is called “partial panel IFR flying.” Essentially, it’s what you do when one of your primary flight instruments fails. In the case of a failed A/I in an aircraft without a backup, you use the airspeed indicator for pitch control, and the turn-and-bank indicator along with the compass for directional control.

Great in theory… but riveting and sweat inducing in reality. My first action was to get the correct pitch attitude set — and quickly — or seven tons of aluminum was going to be out of control in short order with extremely serious consequences to anything below me, people included. That certainly crossed my mind.

I remember one of my instructors, who had taken me on a partial panel training trip, emphasizing: “Slow and easy does it!” Don’t make a bad situation worse by ham fisting the aircraft. So, I started by adding a few jabs of nose down trim, which at least stopped the airspeed decay, now around 190 knots. A few more shots of trim and I was picking up airspeed, slowly at first, then quicker. A shot of aft trim slowed the rate of increase, and when it hit 240 knots, one more jab of aft trim. That seemed to stabilize it in a manageable speed.

With the pitch temporarily solved, establishing the correct heading was next. I had turned to the left on departure, and there was still a bit of left turn on. So a couple shots of opposite aileron trim stopped the turn, pretty close to the vector I was given. This was not the time for perfection — a rough heading would do just fine.

Once I had things more or less stabilized, I calculated that it would take me around five minutes to climb on top of the cloud deck at 30,000 feet.

That was the longest five minutes of my life.

By using just trim, I was able to keep the airspeed between 200 and 250 knots, and the heading within 10 degrees. There was an awful tendency to go back to the A/I, so much so that I put my left hand over it to cover completely.

Did I mention partial panel flying was riveting and sweat inducing?

As I continued to climb, the clouds above were getting lighter and lighter. Sure enough, I finally arrived on top, with a beautiful blue horizon to match. I don’t think I have ever felt so relieved after that incident.

The arrival back at Baden was anti-climactic. The front had moved on, giving clear skies and great visibilities, so it was a standard VFR circuit and landing. Once back at the hangar, I shut down, climbed down the ladder, got down on my knees, and kissed the tarmac. The awaiting technician asked, “Sir, what was that all about?”

I couldn’t wait to tell him.

Once again, another great story Ted. Definitely took a cool hand and intense concentration, but you won the day. Well done.

This brings back memories of my time as a CAF technician in Baden, thank you. I arrived there in January 1979 from Base Flight Cold Lake. Before moving to GTTF (Group Training Transient Flight) I spent 6 months at 439 Sqn line servicing on the CF-104. An astute Warrant Officer noticed the T-33 experience on my records & off to GTTF I went! Although I had had the CF-104 course for my trade in Cold Lake, I hadn’t worked on them there. Ironically, I hadn’t had the T-Bird course but worked on them for a number of years at Base Flight, which had a variety of aircraft including CH-135 Twin Huey & a DC-3. A few months after my move to GTTF I was sent to Shearwater for the T-Bird course.

Had the pleasure of a number of back seat rides in our T-Birds. One as the last aircraft in a massive formation of CF-104s & T-Birds for a parade & several as the tech for repair of aircraft stranded at other bases. The luggage pod that could be fitted on the belly was a useful piece of kit! A memorable trip was from Baden to Athens on a cross country Nav. Midway refuel point at an airport on the outskirts of Rome. With relatively few flights as a tech I can nevertheless relate to that disoriented sensation in thick cloud. We were a 2 plane in formation & IIRC our descent & approach to the Rome airport involved flying through some heavy cloud. I was nervous & sweating as I watched the lead aircraft disappear & reappear as we punched through the layers. Both pilots were old hands, very experienced. 😉 Capt. Tom Potter & Capt. Jim Speiser at the controls.

Being curious I searched Nauen, the destination in the story. Result is a small city just outside Berlin. I don’t recall the exact border for West Berlin before the wall came down but the aircraft would have had to fly through East Germany to get there? I think there was an air corridor for commercial traffic, but a Canadian military aircraft in East German airspace?