By Chris Thatcher | February 25, 2016

Estimated reading time 6 minutes, 40 seconds.

The National Research Council of Canada (NRC) is part of a team trying to accelerate the approval process for alternative aviation fuels. NRC Photo

When the International Air Transport Association in 2009 committed the airline industry to achieving carbon-neutral growth by 2020, it sparked an aggressive search for the next generation of greener aviation fuel.

While that spurred the development of a number of alternative fuels claiming lower emissions and less environmental impact to produce, the process of validating those claims and verifying the fuel’s suitability for aircraft engines has been slow and costly.

The National Research Council of Canada (NRC) is helping to change that.

The NRC is part of a multinational team of research laboratories, universities and engine manufacturers working on the National Jet Fuel Combustion Program (NJFCP), an initiative of the United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to accelerate the approval process for fuels that can be dropped into a jet engine without any modifications.

“We want to identify early on those key properties that a fuel needs so that we don’t have to test it on 20 different engines and use tons of fuel,” explained Pervez Canteenwalla, a research officer with the NRC’s aerospace division. “We want to know what the chemical composition and physical properties a fuel needs to be to run properly in an engine.”

Research into alternative aviation fuels has been underway since the early 2000s when the U.S. Air Force (USAF) began a program to assess substitutes for conventional petroleum-based fuels. But the USAF testing process was both time consuming—each fuel was tested on most engines in its fleets—and costly, requiring producers to provide hundreds of gallons at a time.

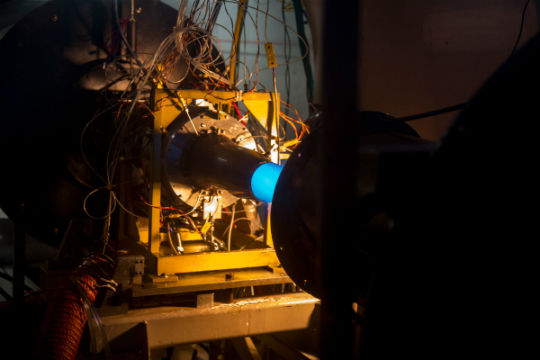

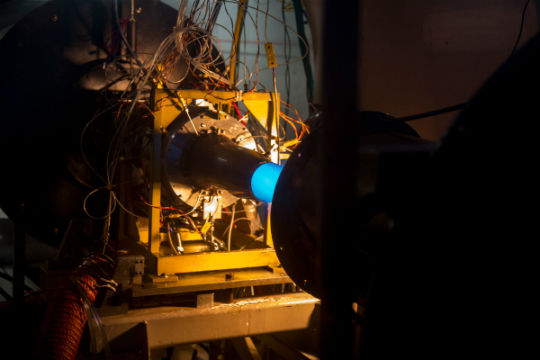

Research into alternative aviation fuels has been underway since the early 2000s when the U.S. Air Force began a program to assess substitutes for conventional petroleum-based fuels. NRC Photo

“For a little fuel producer that has a fuel they think is good, it is a huge risk to produce hundreds of thousands of gallons of a fuel they don’t even know will be approved,” said Canteenwalla. “We want more of these to come onto the market, so we need to accelerate that and de-risk it for these fuel producers.”

Under the direction of the FAA and USAF Research Lab, the NJFCP has brought together engine manufacturers like General Electric, Rolls-Royce, Pratt & Whitney, Honeywell and Williams, among others, as well as leading universities in combustion research and allied partners such the NRC and DLR, the German aerospace centre, to tackle different aspects of the process.

The task of understanding how these fuels behave at high altitude has fallen to the NRC.

In an environmental chamber at the council’s research altitude test facility in Ottawa, a small team is conducting tests on five fuels developed by USAF Research Lab (every research institution is evaluating the same five fuels) by simulating conditions at various altitudes on a Microturbo TRS18 engine.

In particular, the researchers are studying ignition up to 20,000 feet—the ability to restart an engine in cold temperatures is a key concern—and what impact the properties and composition of these fuels have on ignition.

While other labs are evaluating different aspects of fuel composition and combustion, “in the end you want to see what is happening in an engine and see if everything makes sense from the results that the other researchers are getting,” said Canteenwalla. “We want to understand what happens when those [fuel properties] change. So you try to push the engine to its operation limit and see how these fuels perform differently.”

With the push to be carbon neutral by 2020, the demand for alternatives to conventional petroleum-based fuel is high. NRC Photo

In addition to fuel performance, the NRC is also measuring engine emissions. Greener fuels are assessed on how they are produced and “what comes out of the engine when we burn them,” said Canteenwalla.

Working with Environment Canada, the team is measuring the gaseous emissions and particulate matter each fuel produces. While the former appear similar, “the big area where we are getting reductions is in particulate matter, or black carbon soot,” he said. Engine soot is thought to contribute to contrail formations.

“If we are seeing drastic reductions in the soot emissions, maybe we will start to see reductions in contrail formations as well.”

Though the tests are being conducted in the environmental chamber, the NRC has what Canteenwalla calls a “flying emissions lab,” an aircraft able to capture data from the contrails of aircraft it is following. The next phase of evaluation could move from the lab to the sky, he said.

With the push to be carbon neutral by 2020, the demand for alternatives to conventional petroleum-based fuel is high. But as producers trial different feedstocks, the process for evaluating performance needs to be easier and more cost-competitive. Through its research, the NRC is helping identify those few critical tests that will quickly determine whether a jet fuel as the right stuff.